Joan Yeguas

In 1949, along with the main group of paintings from his collection, the portrait of a gentleman – with inventory number 64995 – entered the museum via the bequest of Francesc Cambó i Batlle (Verges, 1876 –Buenos Aires, 1947). On the back of the canvas there was an inscription in French that has since been lost: “Don Luis de Haro, neveu du duc d’Olivares” (Luis de Haro y Guzmán, Marquis of Carpio and nephew of the Count-Duke of Olivares).

Claudio Coello, Portrait of Gregorio de Silva and Mendoza, duke of Pastrana,1688-1692, Francesc Cambó bequest, MNAC 64995

From 1888 onwards the work was ascribed to Murillo (thanks to a catalogue written by Charles B. Curtis), and as a consequence of that, in 1913 August L. Mayer attributed another portrait of the same figure, conserved in the Musée du Louvre, to the painter from Seville (the authorship of the work in Paris is currently ascribed to an anonymous master of the Madrid school).

Anonymous. Madrid School, Portrait of Gregorio de Silva, Musée du Louvre

The story associated with the portrait in the Museu Nacional, known in collecting circles, must have originated in the nineteenth century in France, because of the inscription mentioned above. Until 1857 the painting was owned by the Earl of Shrewsbury, in Alton, England; from 1857 to 1861 it was in the collection of Charles Scarisbrick. In 1883 it was recorded as being owned by Robert Stayner Holford, and later by his son Sir George Lindsay Holford at Dorchester House in London (in old photographs you can see where the portrait was in the great hall) until his death in 1926.

View of the great hall of Dorchester House in London in 1908, where one can observe the portrait by Coello, highlighted in red. Photograph by Bedford Lemere

After that, his heirs put it up for auction, and it was acquired by Cambó in 1928 (in his Diaries, he says that in 1927 he went to London to see the exhibition of the works being auctioned in relation to the Holford Collection).

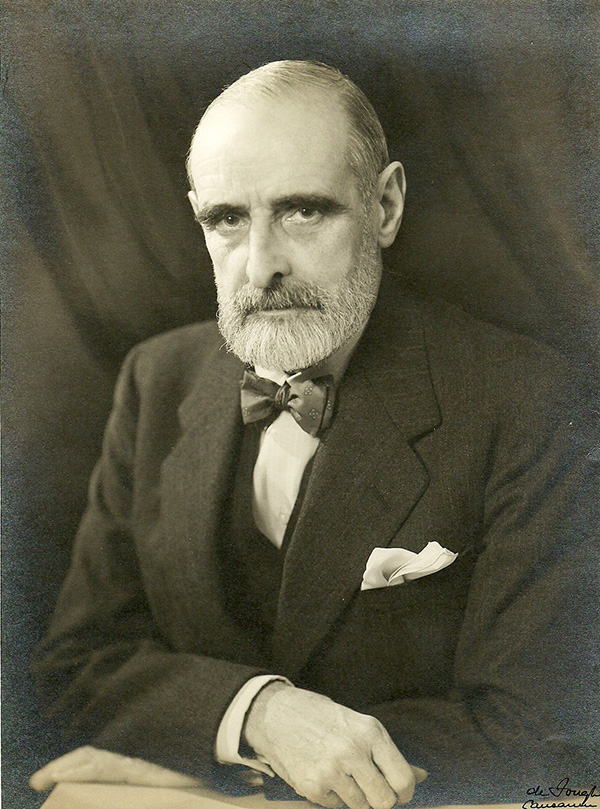

Photographic portrait of Francesc Cambó, Institut Cambó

The identification of Luis de Haro as the subject was ruled out, since despite his political influences and his liking for art he was never decorated with the Golden Fleece (a distinguished order of knights founded in the fifteenth century, historically associated with the Habsburg family – also known as the House of Austria or simply the Austrias). The figure ostentatiously wears the insignia of the Golden Fleece, a chain from which a gold sheepskin hangs, which harks back to Greek mythology – specifically the story of Jason and the Argonauts who went in search of the Golden Fleece.

Insignia of the Golden Fleece. Biblioteca virtual del Ministerio de Defensa

Other authors commented that it could be the Duke of Osuna, following the trend set by the Musée du Louvre (due to an inscription on the back of the painting referring to this aristocrat), but the last member of that family who was a member of the Order of the Golden Fleece died in 1624. It would therefore not fit the chronology of the painting because of the pictorial style and the type of clothes he wears (a prominent golilla, or cloth-lined cardboard garment around the neck, over which was laid a gummed or starched white walloon).

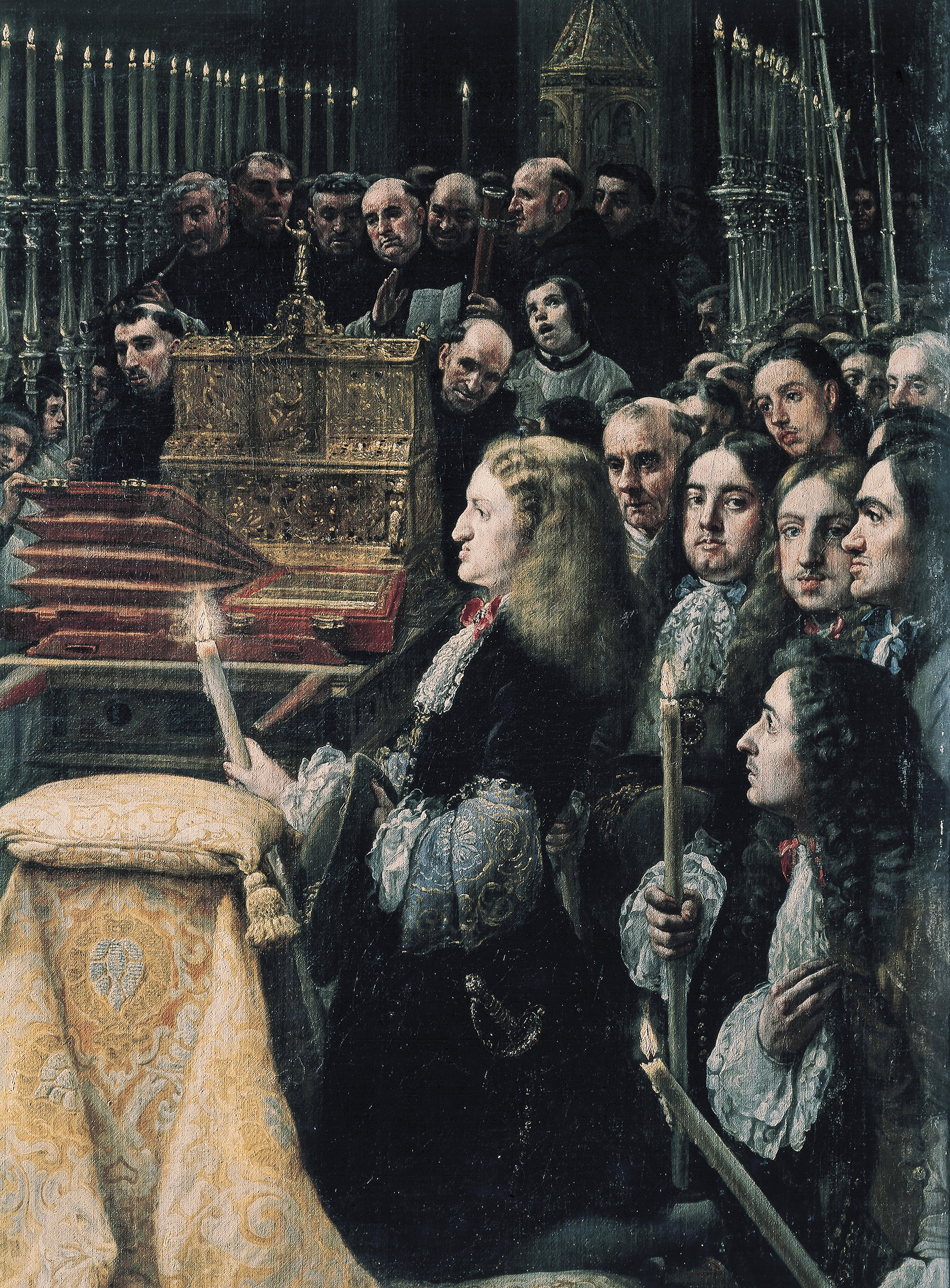

In 1926, Albert Van de Put argued that the subject was Juan Francisco de la Cerda, 8th Duke of Medinaceli (1637-1691), the favourite of King Charles II of Spain between 1679 and 1685. This identification has held firm until the present day; this was the name stated in the credits of our painting until very recently, and also on the portrait in the Louvre. The aristocrat in question had been distinguished with the Golden Fleece in 1670 and he appears in a prominent place in the painting The Adoration of the Holy Eucharist (conserved in the new sacristy of the monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, painted by Claudio Coello between 1685 and 1690). Specifically, he is behind the king, along with different members of the court (it was believed that he was the fat man looking directly at the viewer, whose resemblance to the man depicted in the painting in the Museu Nacional is generally accepted by everybody). The problem is that there may be a great deal of confusion when recognizing the individuals in this retinue.

Claudio Coello, Adoration of the Holy Eucharist (detail), 1685-1690, San Lorenzo de El Escorial (Patrimonio Nacional)

The only irrefutable source is an old description (mentioned in the book written in 1911 by Eustasio Esteban about The Holy Eucharist in El Escorial, which, however, does not clearly state who is who. For example, it says that the Duke of Medinaceli is in the front row, holding a candle in his right hand and his hat in his left hand. However, except for the king, nobody in the painting can be seen holding a candle and a hat.

The true identity of the subject of the painting in the Museu Nacional is Gregorio de Silva y Mendoza (Pastrana, 24 April 1649 – Madrid, 15 August 1693), 4th Duke of Pastrana (after the death of his father in 1675), 9th Duke of El Infantado and 7th Duke of Lerma (after the death of his mother in 1686), among many other noble titles.

On 15 December 1687 he was made Sumiller de Corps, a royal appointment that placed him in direct contact with the king and the royal household, until he was decorated with the insignia of the Golden Fleece on 11 May 1693, just three months before his death. This identification hypothesis was not new, because in 1919 Juan Allende-Salazar and Francisco Javier Sánchez Cantón, in the book Retratos del Museo del Prado. Identificación y rectificaciones, considered him for the version of the portrait conserved in the Musée du Louvre, for two reasons: 1) stylistically it could not be by Murillo (a claim that was repeated insistently at the time, and completely ruled out after the monograph Diego Angulo wrote about the painter in 1981); 2) the subject was the Duke of Pastrana because he is close to the king in the description of the painting of the Holy Eucharist.

Claudio Coello, detail of Gregorio de Silva in the Holy Eucharist (Patrimonio Nacional).

In a letter written to The Burlington Magazine in 1926 they contradicted Van de Put, stating that it could not be the Duke of Medinaceli because it looked nothing like an engraved portrait of him made by Antonio Verga in 1658. In 1931, Mauricio López-Roberts also believed that it was the Duke of Pastrana, although he mentions another portrait (very similar to the work in the Museu Nacional, possibly a copy), which was in the collection of the Duke of Fernán Núñez, seized during the Spanish Civil War and whose whereabouts are now unknown.

Anonymous. Madrid School, Portrait of Gregorio de Silva (former collection of the Duke of Fernán Núñez).

The puzzle has been solved once and for all with the appearance of a new portrait, an anonymous work painted from Coello’s models, auctioned on 3 November 2021 at Setdart (lot no. 35121890), whose subject is the same as the one we are analysing, with the novelty that there is an epigraph identifying him as “el Eccmo. Sor. Duque de Pastrana, grande de España, del consejo de S. M. y caballero del toysón de oro”. With this we can begin to compare it with other known portraits of the Duke of Pastrana, especially the well-known work by Carreño de Miranda conserved in the Museo del Prado, dated 1679, in commemoration of some diplomatic work in Paris.

Anonymous. Madrid School, Portrait of Gregorio de Silva (Setdart Subhastes).

In view of the portraits conserved, I would establish a slightly earlier date, perhaps 1674 (when he was designated a Gentleman of the King’s Bedchamber) or 1675 (when he inherited the duchy on his father’s death). The portrait in the former collection of the Duke of Fernán Núñez presents a fairly good likeness to the portrait in El Prado, and it would confirm the figure’s identity; this painting, now lost, could be dated between 1680 and 1685.

Juan Carreño de Miranda, The Duke of Pastrana, circa 1679 (1674-1675?), Museo Nacional del Prado

The date of the portrait in the Museu Nacional must be established somewhere between 1688 and 1692. That is, between the coordinates of two axes: 1) from the moment he began discharging his duties as the Sumiller de Corps (December 1687), when he would have come into close contact with the king and the most important members of the court; 2) Coello’s style is crystal-clear, but one must also bear in mind that he was appointed court painter in 1685 (due in part to the deaths of Francisco Rizi on 2 August and of Juan Carreño de Miranda on 3 October of that year), and was the court’s preferred choice until the arrival of Luca Giordano in Madrid (May 1692). We should be thinking that the insignia of the Golden Fleece was added after the date on which it was conferred on the duke (May 1693), just as the cross of the Order of Saint James was added to the self-portrait of Velázquez in Las Meninas a few years after he painted the famous work.

Joan Yeguas

Art del Renaixement i Barroc

Related links

https://blog.museunacional.cat/una-serie-inedita-del-pintor-cajetan-roos-o-gaetano-rosa/

https://blog.museunacional.cat/una-trinitat-trifacial-al-museu-nacional-dart-de-catalunya/

Art del Renaixement i Barroc