Francesc Quílez and Aleix Roig

The exhibition The Heartbeat of Nature is intended to be an immersive experience, given that it immerses us in the relationship, the very close contact, that in the nineteenth century artists established with the physical environment, and how this connection was transformed into a very fruitful response, which gave rise to a large number of creative productions. Among other things, these works clearly show the existence of an empathetic and emotional relationship, of respect and veneration for nature, which is the main protagonist of the show. At a moment in history, like the present one, in which people have become increasingly divorced from the land, the theme provides a forum for reflection on the importance of nature in the construction of an aesthetic ideal, far removed from the sentimentalism and the seclusion to which the landscape painting genre reduced and subjected it. When the effects of environmental depredation are in evidence everywhere, when concern for the effects of climate change, especially global heating, is at the heart of social and political debate, the works exhibited hold a mirror up to us and expose the limitations and the weakness of an exhausted model of growth.

Jaume Morera. The Seine. Outskirts of Le Havre, port of Rouen, 1884. Oil on canvas, 87,8 x 163 cm. Col·lecció del Museu d’Art Jaume Morera de Lleida (MALL 0319)

Even though it is merely a historical fiction or a uchronic construct, we cannot help thinking, even as a working hypothesis, to what extent things might have been different if, at the fork in the road created in the early nineteenth century by the triumph and the expansion of Enlightened ideas, the human condition had had the chance to reconcile nature with civilization, as the philosopher Friedrich Schiller wrote in his work Letters Upon the Aesthetic Education of Man. It is obvious that if this second option, which was pushed into the background by historical positivism and technological progress, had been successful it could have made a different kind of growth possible, far more sustainable and balanced, without running the risk of the over-exploitation of energy resources in which we are currently immersed. With their attitude, even though they were not ecologically aware, the artists of the nineteenth century beat an alternative path that is still totally valid today because it foreshadowed the emergence of a sensibility that forces us to stop and think twice about the sense of many of the decisions that affect our closest ecosystem. Intuitively, like a mood, or a feeling that is more superficial than rational, with their artistic productions, very often described as aesthetic bagatelles, without meaning to, the artists of this period constructed a strategy for raising awareness in society that was far more effective than any big publicity campaign.

Despite the fact that the painting of nature has always been part of the Western artistic tradition, and historically it has aroused the interest of artists, it was not until the nineteenth century when it began to occupy a predominant place and was transformed into one of the themes most visited by the European figurative culture of the time. Prior to that, it had played a minor role, always acting as a backdrop for the purpose of framing pictorial narratives, without ever developing a dimension of its own. In earlier artistic tradition, it never had the opportunity to grow as a genre with its own characteristics. Its presence was justified because it acted as an extra, because it dignified the actions, offered variety and decoratively enriched the painted scene.

Without wishing to be reductionist, or wanting to establish a cause-effect relationship, we can claim that the emergence of this theme is in large part due, paradoxical though it may seem, to the phenomenon of industrialization and the resulting growth of the big cities. This transformation also represented a cultural change that was extremely important for the habits and the behaviour of a population that for many centuries had lived mostly in rural settings, and which in a very short period of time – and without having time to come to terms with it – found itself forced to move to live in urban centres constructed on a totally different system of values and physical reality.

Nicolau Raurich. Suburbs of Barcelona. Hacia 1909. Óleo sobre lienzo. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The image of communities, virtually self-sufficient, that had generated a feeling of respect for the environment, which were part of an ecosystem in which remained in equilibrium and direct contact with natural surroundings that were part of an individual and communal identity, gave way to a model of social organization based on the idea of the depredation of the environment, the disappearance of any vestiges that might overshadow the predominance of technological power. Without turning into a nostalgic expression, it was the poetic voice of Baudelaire that best expressed the feeling of social estrangement experienced by the new inhabitants of these artificial paradises, when in one of his poems he evoked the chiming of the bells on Sundays as the last sound that connected the centuries-old past, associated with the rural way of life, with the urban present. In some ways, the landscape genre, which experienced its high point in this context of transformation, performed a symbolic function, very similar to that fulfilled by the sound of an instrument such as that of the church bell. It became a nostalgic evocation, a feeling of loss of an ancient worldview that was already irretrievable, because the idea of progress was unstoppable and could not be allowed to look back.

Lluís Rigalt, Night landscape with ruined monastery. Circa 1850. Pen and ink on paper. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Landscape painting, as a genre, basically became the instrumental resource of the new industrial bourgeoisie for overcoming the syndrome of social alienation brought on by the absence of nature. Without underestimating the creative impulses that drove many artists’ need to depict the forms of nature, to transform them into aesthetic expressions, the existence has to be mentioned of heavy demand for artistic items, many of them sumptuous and destined to display their owners’ high purchasing power, and also to provide an outlet for the love of ostentation that modulated the criteria of aesthetic taste in the period. In this respect, painters had to adapt to a demand highly conditioned by a particular perception of nature, which gave rise to a sentimental projection of the landscape. The landscape painting made up for metaphysical deficiencies and supplied spiritual and aesthetic nourishment, almost as if performing the functions of a cathartic tool, of a society that was based on implacable historical materialism, in which the city was the visible sign of the transformative power of progress and industrial growth. From this perspective, the landscape genre also consolidated the countryside’s refusal to become an alternative model of social organization that could be based on other principles, values and a more sustainable and balanced ideology – in a word: far more respectful of the environment.

Jaume Morera. Sierra de Guadarrama (Cabin), 1891-1897. Oil on canvas, 42,5 x 72,3 cm. Col·lecció del Museu d’Art Jaume Morera de Lleida (MALL 0087)

The countryside was looked down upon with disdain and a feeling of superiority by elites who saw it as a relic of the past, a hindrance that had to be neutralized. They therefore turned it into a picturesque scene, designed to satisfy aesthetic needs, and defused any danger that might not make it possible to sanctify and venerate the myth of progress. This bourgeois ideological instrumentalization gave rise to the appearance of two conflicting worldviews, two exclusionary systems that saw the countryside presented as the antithesis of the city and identified with a reactionary set of ideas. The division, approached almost as a Manichaean exercise, given that it denoted a very reductionist view, led to the creation of a deceptive separation which made it impossible for the two worlds to be reconciled with one another, or even bridges of mutual understanding to be built between them.

The present show focuses on this close relationship between art and nature, creating the present discourse from the specific elements that form this symbiosis. Broadly speaking, one of its objectives is to pose the need to reflect on and redefine some of the historical categories that are part of the historiographical baggage. In this respect, it is essential to take a self-critical approach and banish the instrumental resources, the conceptual apparatus with which the analysis and the study of the landscape genre have traditionally been tackled. In methodological terms, we believe it is necessary to supersede old concepts, theoretical a priori assumptions and dogmas, as they do not help to bring this theme up to date, to approach it in a much more efficient way, without simply repeating the traditional historiographical conventions and models. We believe that this way it will be far more attractive and it will help to make it much more current.

After all, we must remember that landscape painting was one of the themes most developed by Catalan artists in the nineteenth century, and this fact, with its evident specific importance, has led to it being one of those most studied by our historians. The majority of these analyses, however, have simply repeated the cliches and the stereotypes of Anglo-American and French historiography, with a tendency to automatically transfer models that correspond to the application of a criterion of homogeneity that has not taken into account either the diversity or the variety of other discourses. The result has been the maintenance of these models, considered to be canonical, universal and useful for the interpretation of any artistic reality. Due to this, however, the surprising paradox has arisen that a fact of artistic, almost identitarian, singularity, the interest that Catalan artists felt for the representation of nature, far from being an attitude of diversity, of specificity, continues to be treated without the necessary intellectual rigour with which it ought to be, since the tendency is to repeat the canonical interpretative schemes. This absence of alternative approaches that study the reality of nature with a different historiographical mentality, more suited to the influence of other disciplines, like sociology, biology, philosophy or ecology, has contributed to the disparagement and the impoverishment of exhibitions dedicated to landscape painting. In the eyes of the general public this kind of show has become monotonous and boring.

The cultural institutions, with their lack of ambition, risk and boldness (despite the renewal of their narratives), have found it difficult to find a place for pictures of landscapes. Thus, far from being incorporated in a global discourse, they have very often become areas separated from the rest of the collection. This deprives them of a more dynamic relationship, one of dialectical comparison with other themes, the majority of which represent the values and interests of a hegemonic, dominant class, the bourgeoisie, which lasted for the entire nineteenth century. The absence of interaction with the rest of the genres that shaped the aesthetic and iconic idiosyncrasy of this period has condemned landscape painting to ostracism, or to becoming a systemic anomaly, a sort of refuge destined to meet the needs of individuals in contemporary societies to disconnect, or what many biologists have defined, in an instinctive response, as “biophilia”, in reference to the empathy we feel for the living world, the positive mood we feel when gazing upon the spectacle of the metamorphosis of nature.

With the aim of reformulating traditional ideas, what we have tried to do is construct a narrative that supersedes these conventions, avoiding classifications by styles or artistic movements. We have to a certain extent wished to remain faithful to the idea that the classical authors formulated, who used two expressions to distinguish between natura naturans, in reference to the biological, evolutive sense, to the permanent change in which natural forms are immersed, and natura naturata, which would correspond to human visual perception, akin to a fixed, static photograph of the landscape at a particular seasonal moment. Therefore, in order to respect this principle, we have used a more conceptual terminology, adapted to the original sense that characterizes the reproductive meaning of nature. From this point of view, we have attempted to reflect the existence of a boundless nature that we have wished to deconstruct on the basis of the elements that form it, breaking with an idea of the landscape as something finite, static and closed. In other words, we have avoided the landscape painting genre, subjected to the directives of a bourgeoisie that attempts to dominate nature, of a finished product that satisfies the longings of those who see something rural and wild as a pleasant colonized garden. On the contrary, we have opted to display the idioms that are closest to the direct experience of nature.

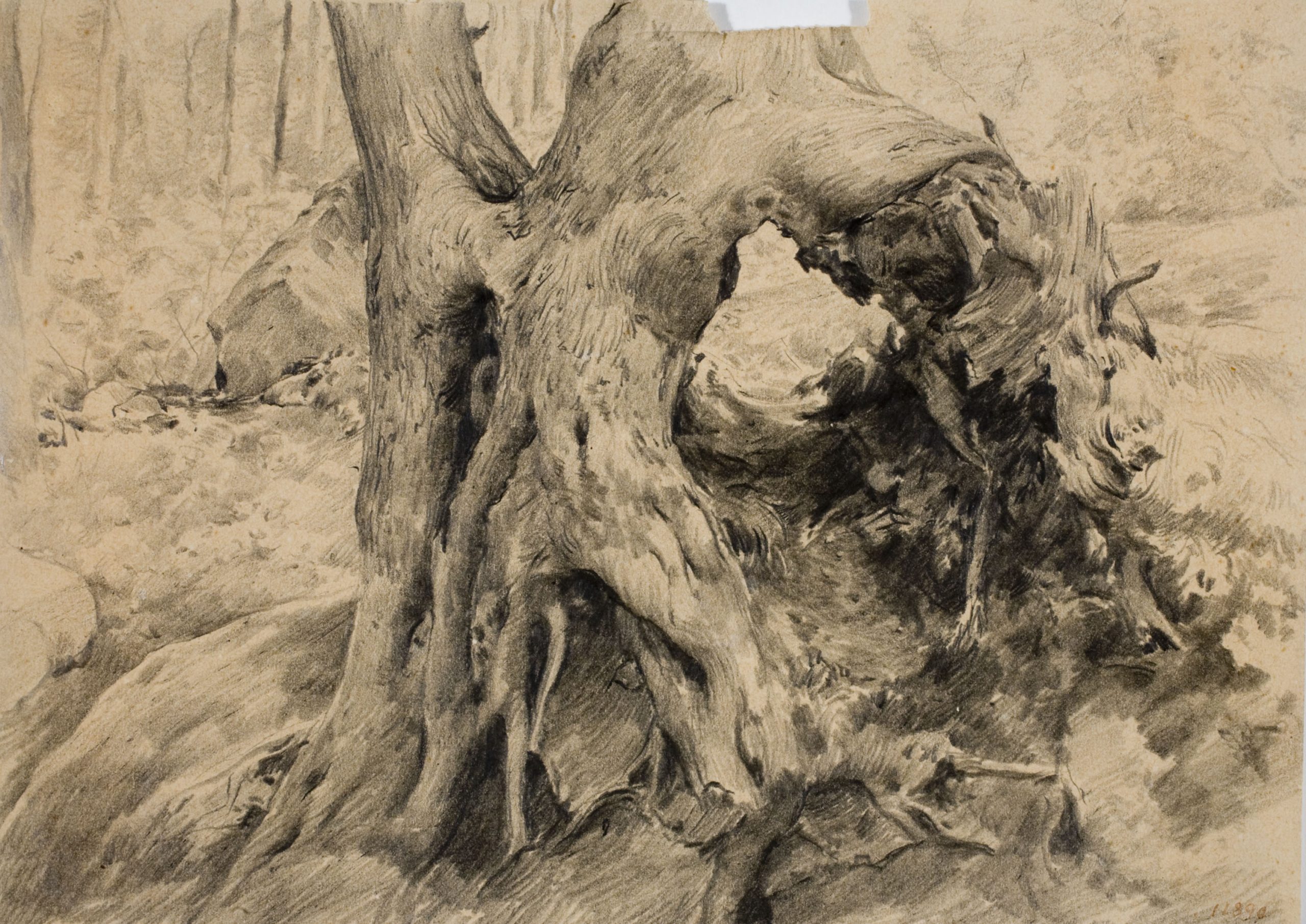

Antoni Fabrés. Forest corner. Circa 1888-1894. Graphite pencil on paper. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

However, besides the most picturesque and paternalistic views, many landscapes of the period are determined by a marked pantheism. They are sublime scenes, of unattainable horizons that usually end up as religious beliefs because based on their magnificence they strengthen belief in God. Aside from this religious or doctrinaire dimension, it is true that certain philosophical schools in the period made a spiritual reading of the Romantic movement, seeing the triumph of Enlightened Reason as a very expensive price that the human race had to pay and which generated an unmistakeable loss of spirituality. These thinkers, especially in Great Britain and Germany, wanted to repair this division by turning their gaze towards nature and shaping a pantheistic spirituality that while it never became a creed, did bring back a feeling of transcendence that overcome the immanence of Enlightened thinking.

Jaume Morera. Peñalara (Sierra de Guadarrama). Circa 1904. Oil on canvas. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

It was a case of binding (religare) the physical part of the human condition to the metaphysical dimension for the purpose of completing the conquests of freedom and emancipation represented by the emergence of Encyclopaedist thinking. In this respect, the uncertainty caused by the loss of a supernatural explanation that, up to then, had attenuated the materialist view of existence, led to the appearance of a feeling of dissatisfaction. The latter is a philosophical idea that has often been put forward to explain the veneration that the Romantics felt for nature and the fact that many of them decided to convert to Catholicism, dissatisfied with the inadequacies of rationalist logic that observed the phenomenal events of nature with the coldness of the laboratory scientist, which adopted an insensitive attitude, unexcited, unmoved, and was incapable of moving on from the logic of the chain of universal causation. For them all natural phenomena had a scientific explanation.

Unlike British thinking, which ended up as a school of poetic sublimation of natural reality, something that gave rise to the appearance of a large number of poetic voices, the German interpretation crystallized in a school of thought, idealism, that looked closely at consequences and many of the ideas in Kant’s philosophical system. With the publication of his three critiques, Critique of Pure Reason, Critique of Practical Reason and Critique of Judgement, Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), besides grounding and assimilating the ideas of other authors, including those formulated by the philosopher Edmund Burke (1729-1797), who in 1756 published the book A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, in which he proposed the theory of the sublime, one of the ideas that the post-Kantian aesthetic found most attractive, Kant laid the foundations of the mechanisms of the functioning of the human mind and at the same time, in his last critique, he attempted to establish how aesthetic judgment functions, something that, against his wishes, caused a crack to appear in his epistemological edifice.

Kant’s limitations, or incapability, when it came to defining the nature of aesthetic experience aroused the interest of a first group of thinkers, those of the Jena School, who sought a system capable of overcoming the separation existing between the subject and the object. By extension, this system penetrated the nucleus, the essence of the thing in itself, something that Kant had already sensed but not resolved.

Despite the existence of different types of responses, which ranged from the idealism of the transcendental Self of Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814), the theory of the genius, also transcendental, as a kind of superman, which foreshadowed the ontology of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), upheld by Friedrich Schelling (1775-1844), or the aesthetic inclination upheld by Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), all these authors agreed to sublimate the importance of nature and its impact on transformation into artistic and aesthetic forms, in which the creative genius became a kind of alter ego of divinity.

Eugenio Lucas. Riverside landscape. Circa 1850-1960. Watercolor and ink wash on paper. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

As we have said, in Letters Upon the Aesthetic Education of Man, written by Schiller in 1795, he proposes that the experience of beauty is the solution, the healing balm, that will make it possible to resolve the split nature in which man lives, divided between the natural and the rational state. The German thought that art could cauterize this wound and could be transformed into a form of knowledge far superior to any other form of access to wisdom, because it contained the properties of the pairing and would help to reconcile sensibility with discursive logic or the primitive state with the state of civilization. The poet and philosopher went further and proposed a form of political, social and moral organization called the aesthetic state, in which beauty was a fundamental pillar.

Having said that, the types of works selected in The Heartbeat of Nature shies away from the more conventional, stereotyped and canonical views of the physical surroundings. We have avoided reconstructing the history of Catalan landscape painting, grouped together by an orderly structure based on artists and movements. The connecting thread of the proposal has been to visualize the chaotic, disorderly, wild and primitive image of nature that refuses to be neat and tidy, to be enclosed and parcelled up by human activity, which exploits it, cultivates it and eventually transforms it into a colonized product.

Ramon Martí i Alsina. Landscape. Hacia 1870-1880. Lápiz conté y lápiz grafito sobre papel. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Indeed, the principle that we have intended to bring to the fore is metamorphosis, of nature that is undergoing a permanent process of change, of transformation that does not match the mirage of unspoilt, unchanged nature. The images chosen clearly show the stimulus represented for many artists of the period by direct contact with nature, which they approached with an open mind, free of prejudices and without pre-established ideas, stemming from pure feelings. We thus avoid the longing that wishes to convert nature into an extension of the garden behind our house, a deceptive, domesticated garden, due to the neutralization of the wildest and most untamed aspects.

In general terms, they are works that clearly show a communion with the physical space, an idea of cosmic unity, a reverential respect for the soul of nature, for what the Swiss philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), upon referring to this physical reality in his various works, like for example Letters Written from the Mountain (1764) or Reveries of the Solitary Walker (1778), called the barometer of the soul; all of them aspects that foreshadowed the appearance of a sensibility, a feeling of respect for the environment, nowadays transformed into political ecological activity, something that confirms the validity of a principle of sustainability that was established as an alternative model to that of the depredation of the natural environment.

Lluís Rigalt. Views of Montserrat. Circa 1873-1874. Ink wash and graphite pencil on papel. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Obviously, the artists of the time did not have an ecologist’s awareness, in the sense of activism, as at that time there was none of the current concern arising from the existing climate crisis. However, the reverential respect for the forms in which nature expresses itself does connect with the current sensibility towards the environment.

And yet, there was already a polarization between two conflicting models in the nineteenth century. On one hand, economic and technological growth based on Enlightened Reason became a dogma of faith that announced man’s triumph over nature. Human happiness was thus associated with the technological utopia that would make people’s emancipation possible, as well as a greater degree of political and social freedom, and greater economic wellbeing. It was a model of boundless depredation of natural resources, in favour of unstoppable progress. Unfortunately, the limitations of this model based on the absolute exploitation of the environment with the aim of generating a dynamic of unlimited growth were clearly seen throughout the twentieth century. The idealistic falseness of historical optimism is there for all to see, a mirage that believed that the available resources were unlimited, as were the benefits this would produce for our species. History, according to Hegel’s interpretation, was the framework in which the idea of the spiritual emancipation of the human condition was developed, and for our part, we can only add that colonialism was the spearhead of this policy of domination defended by the European powers.

In contrast to that, without disowning the ideology and the defence of Enlightened philosophy, at the end of the eighteenth century in Europe there emerged a school of opinion that began to view the way things were going with concern, questioning the absolute value of Reason and standing up for the need to unify the divided part of the human condition, that which bound it to nature, as an element that completed and unified the physical, natural part of the person, given that we are all the product of nature’s work.

As we said above, one of the triggers was the publication and dissemination of Kant’s Critique of Judgement. The text stimulated a large number of thinkers to seek a philosophy that would cover the orphanhood brought about by the expansionism of the Enlightenment, which had been capable of finding explanations to physical phenomena that up to then had found no logical and rational explanation but which had indirectly divested nature of its mysterious and spiritual aura. In this respect, Critique of Judgement made it possible to open up new avenues of unknown wisdom and experience, and metaphysical needs that had not found a satisfactory answer.

From this perspective, all those who still believed in the existence of supersensible spiritual forces and saw them reflected in nature, attempted to find, in their search for beauty, in aesthetic experience, a path that thanks to the mediation of nature might make the goal of reconciliation possible between the rational and the spiritual part of the human condition, which, according to this interpretation, Enlightened Reason had helped to divide.

Baldomé Galofre. Landscape. Circa 1880-1886. Charcoal on colour paper. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya