Àngels Comella and Joan Yeguas

In the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya (Barcelona) and the Museo Nacional del Prado (Madrid), two virtually identical portraits are conserved. This leads us to formulate different questions. Could both paintings have been done by the same artist? If they were, what part did the painter’s workshop play in it? Is it possible to find out which one was done first? Which was based on which? Was tracing used, or grids in the process of execution? Is it an original or a later copy? In the Museu Nacional a comparative study has been made of these two works for the purpose of shedding some light on the matter, and in this post we present the results obtained.

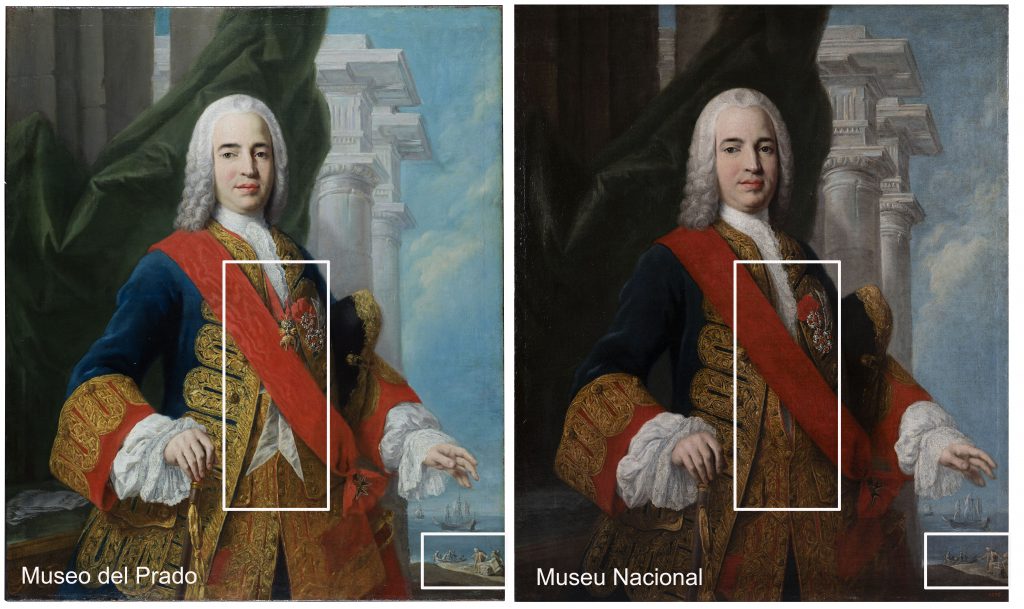

Jacopo Amigoni, Portrait of the Marquis of La Ensenada, 1747-1750, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya / Jacopo Amigoni, Portrait of the Marquis of La Ensenada, 1747-1750 ©Museo Nacional del Prado

In the Museu Nacional’s collection of Renaissance and Baroque painting there is a portrait, acquired in 1904 by the Municipal Board of Museums and Fine Arts of Barcelona (MNAC 11598), to be precise, an oil painting on canvas measuring 123 x 101.5 cm. The work is attributed to Jacopo Amigoni (Venice, 1682 – Madrid, 1752), a painter and engraver active at the courts of England and Spain, as well as for the German nobility, where he developed a cheerful style with rapid and luminous brushstrokes in easel paintings (he was a highly appreciated portrait artist) and in decorative murals (ceilings and vaults), which has led to him being considered an outstanding artist in European painting in the second half of the 18th century.

The work is a portrait of Zenón de Somodevilla y Bengoechea (Hervías, 1702 – Medina del Campo, 1781), better known as the Marquis of La Ensenada, a Spanish politician who climbed much of the bureaucratic ladder, from when he entered the Naval Ministry as a supernumerary (in 1720) to when he was dismissed from his government posts (1754) and eventually banished after the Esquilache Riots (1766). Thanks to reorganizing the navy and the subsequent reconquest of Sicily (1735), the following year (1736) he was made a marquis. He had a meteoric career: secretary of the admiralty (1737), knight of the Order of Calatrava (1742), secretary of the Treasury, War, the Navy and the Indies (1743), state councillor to Kings Philip V and Ferdinand VI, captain general of the navy and the army (1749), knight of the Golden Fleece (12 April 1750), and knight of the Grand Cross of the Order of Malta (27 October 1750).

Jacopo Amigoni, Portrait of Ferdinand VI (Villa Canossa, Garda) / Jacopo Amigoni, Portrait of the Marquis of La Ensenada, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Different copies of portraits painted by Jacopo Amigoni of the Marquis of La Ensenada are conserved, of uneven quality, which must be dated to between 1747 and 1750, that is, between Amigoni’s arrival in Madrid (recorded from 1 November 1747) and the marquis being granted the Order of the Golden Fleece (on 12 April 1750). There are, however, two different types of portrait, both painted by Amigoni with more or less help from the workshop.

One model, from which the work in the Museu Nacional derives, clearly emulating royalty, comes from the portrait of King Ferdinand VI (125 x 104 cm), made around the same time and conserved in the collection of the Marquis of Canossa (in Garda, Verona), with a similar arrangement of curtains and architectural features in the background, and, above all, the position of the hands (in the portrait of the king, his right hand rests on his waist and his left hand on a table, but in the picture of the marquis it was changed: the right hand was resting on a staff of command and the left hand waving in the air). In this group we find a portrait mentioned at the beginning, very well-known and almost identical to the one in Barcelona, in the Museo Nacional del Prado (P002939), which is very similar in size (124 x 104 cm). Following this same type, there are other versions, such as a portrait that was sold in Rome in 1965 or another that was auctioned on 26 May 2016, (Balclis, lot 1636, with a neutral background and smaller in size: 80 x 61.5 cm).

The other model has a similar background, but it has some variants, above all in the position of the hands (in this case his right hand is close to his chest and his left hand on his waist), such as the portrait that is conserved in the collection of the Marquis of Santillana, of which there are other copies in Madrid (Museo Naval and Palacio del Senado).

Three portraits by Jacopo Amigoni of the Marquis of La Ensenada: Museo del Prado; Collection of the Marquis of Santillana, Madrid; Palacio del Senado, Madrid. In which the painter paints the same architectural features and curtains in the background.

As we said above, in the Museo del Prado there is a similar replica of the “Portrait of the Marquis of La Ensenada”. We thought it was a good time to analyse the two works comparatively, in order to find out which one was painted first, if one served as a model for the other, if the two are based on a third work, or if the composition is the sum of the different tracing templates.

Although the portraits in the Prado and the Museu Nacional are very similar, there are some details that differentiate them. At the Museu Nacional we have attempted to learn more about the works through the study of the painting technique, the presence of an underlying drawing and the materials used. In order to conduct this study we took general and detailed photographs with visible light, ultraviolet light images (UV), X-Ray imaging (XR) and infrared reflectography (IRR).

The images with visible light show two exactly identical portraits, with the same figure, the same clothing, the same background details; that is, with an almost identical model and composition. Even so, by placing the images side by side we have been able to observe two significant differences:

General images of the portraits in El Prado and the Museu Nacional where two areas are pointed out: the badge of the Golden Fleece and a maritime scene in the background.

- In the version in El Prado, the marquis is wearing the badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece on his chest, whereas in the version in the Museu Nacional this medal is missing.

- In the work conserved in Barcelona we can see that the maritime scene in the background (with figures) is slightly mutilated in relation to the one in El Prado, as only one arm of the figure on the far right and part of the merchandise he is transporting can be seen.

Comparison of the details, in which it is observed that in the portrait in the Museu Nacional the badge of the Golden Fleece and part of the maritime scene are missing.

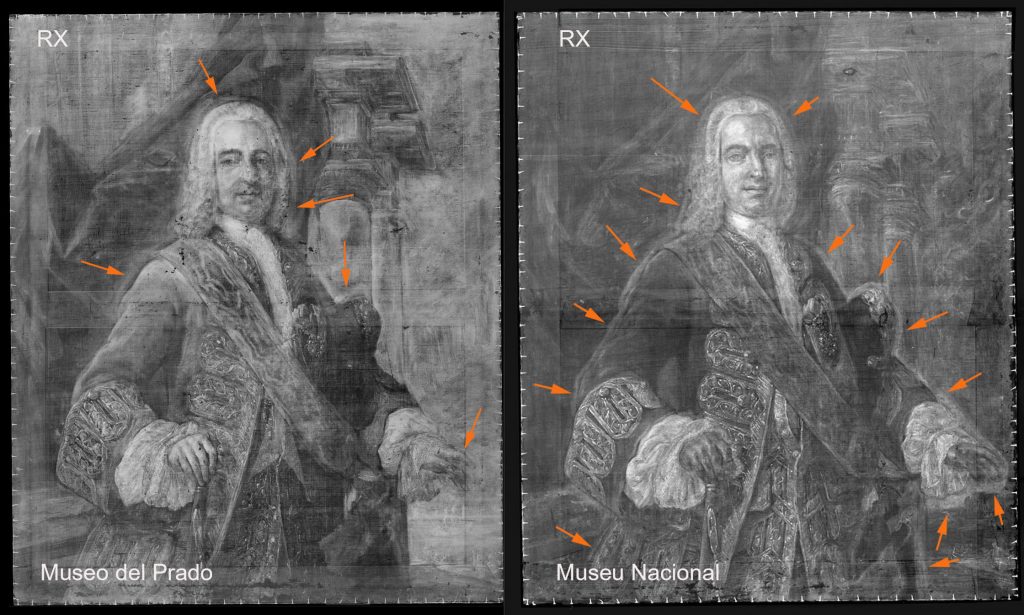

The images of the paintings obtained with XR and IRR help us to discover what lies hidden underneath the visible paint layer, such as the corrections made during the creation of the work, the signs of the use of tracing, the details of underlying drawings or the use of a grid. In this case, the X-ray images correspond completely with those of visible light. This means that, curiously, in neither of the two portraits can pentimenti or corrections made by the painter be detected, aside from the aforementioned addition of the Golden Fleece to the picture conserved in Madrid.

Comparing the X-rays of both paintings, we realize that the present stretchers are not the original ones. The X-ray images also show up small dark blotches, which correspond to old losses of colour, now restored, which were undoubtedly caused by the wear and tear of the original canvas on the old stretcher, something that indicates that the works are old and contemporaneous.

General XR images that allow us to observe the fitting in of the figure with a light-coloured brushstroke. ©X-Ray imaging. Technical Studies Archive and Laboratory, Museo Nacional del Prado / X-Ray imaging: Comella, Martí, Masalles, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

In the XR image of the work in the Museu Nacional there is a light-coloured brushstroke that runs around the entire outline of the figure. It could be a case of fitting it in the composition during the process of execution. Some outlining brushstrokes are also detected in the painting in El Prado, but they are far more subtle in this case.

The XR images of the painting in the Museo del Prado also reveal a greater radiographic contrast in the use of white colours, mainly in the hands, the architectural features and the background of the painting.

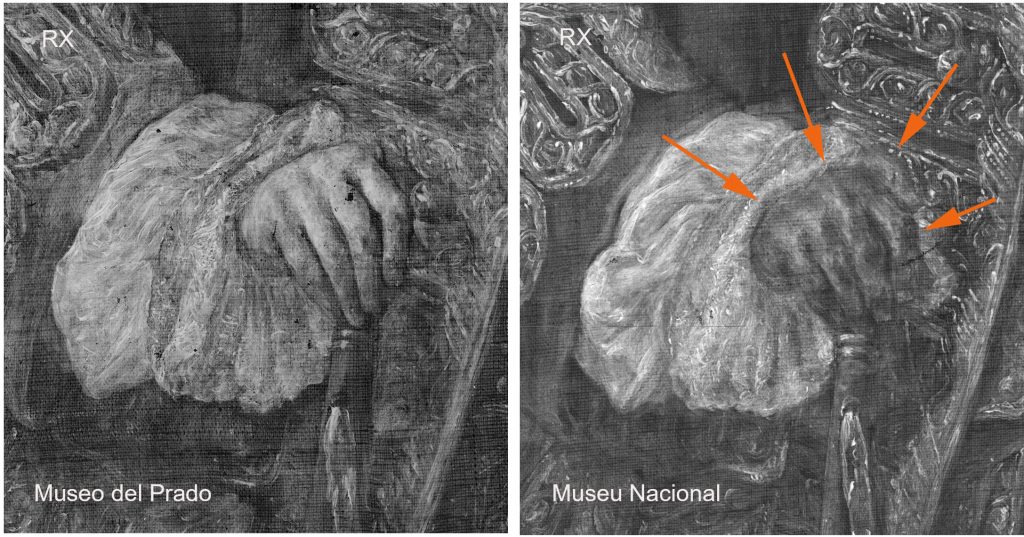

Comparison with XR of the detail of the hands, in which greater radiographic contrast in the flesh tones can be detected in the work in the Museo del Prado. ©X-Ray imaging. Technical Studies Archive and Laboratory, Museo Nacional del Prado / X-Ray imaging: Comella, Martí, Masalles, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

In the X-ray images of the painting in El Prado we see that Amigoni painted the marquis’s unbuttoned waistcoat in great detail. This is highly significant as it enables us to conclude that the badge of the Golden Fleece was added after the portrait was done; this refutes the hypothesis of the scholar Jesús Urrea (La pintura italiana del siglo XVIII en España, Valladolid, 1977), who claimed that the work in Barcelona was earlier, due to the fact that it did not have the badge of the Golden Fleece hanging.

Detail of the portrait in the Museo del Prado: first with visible light, second with XR, and third with IRR. It can be seen that underneath the layer of paint in the area where the badge of the Golden Fleece is, the painter only painted the unbuttoned waistcoat originally. ©X-Ray imaging. Technical Studies Archive and Laboratory, Museo Nacional del Prado / Infrared Reflectography. Technical Studies Archive and Laboratory. Museo Nacional del Prado

As we mentioned above, in the IRR images the lack of compositional changes and pentimenti is confirmed. Simply, and very subtly, a line of underlying drawing can be seen, applied with the brush on the outline of the face and on the eyes in the work in the Museu Nacional. In the clothing there is a sharper line, done dry with a stick of charcoal. Apart from that, in neither of the two works analysed can signs be perceived of the use of templates habitually used by workshops to make replicas. Reflectography also shows the pictorial treatment that the artist gave it: in the case of the Barcelona portrait, first the columns were painted and then paint was applied to the background, outlining the profiles; on the other hand, in the work in the Prado, architecture and background were worked on simultaneously. In the IRR image, the details of the finished painting beneath the place where the badge of the Golden Fleece appears is also clear, something that confirms the hypothesis put forward previously that the said badge was added later.

General image with visible light of the portrait in the Museu del Prado, on which the outline of the portrait in the Museu Nacional has been superimposed (marked for us with white lines). This makes it possible to observe a slight displacement of the composition to the right.

Finally, with the aid of an imaging processing program, we have superimposed a tracing of the painting in the Museu Nacional over the one in El Prado. It can be observed that the heads of the two figures of the Marquis of La Ensenada fit exactly and clearly. In the rest of the composition, however, the drawing was gradually displaced to the right, a circumstance that is explained as the result of the process of using a tracing template. A slight error in the use of the template displaced it beyond the edge of the painted surface, the reason why part of the figure on the far right of the maritime scene is missing (only part of his arm can be seen, as we said).

In conclusion, the studies carried out up to now enable us to claim that the two versions of the portrait of the Marquis of La Ensenada (Museu Nacional and Museo del Prado) come from the same model and have undergone a very similar material ageing process. The comparison of both works shows up significant differences, like the presence of the badge of the Golden Fleece and the figure in the background maritime scene. The images obtained with XR and IRR show, on one hand, that the badge was added after the portrait was made, given that the painting underneath shows the figure’s clothing in detail; and, on the other, no trace of a grid or the use of a template to make the preparatory drawing has been clearly detected. Despite that, the superimposition of the two versions allows us to corroborate the hypothesis of the use of a template in the version in the Museu Nacional that is slightly off-centre to the right (due to a slight error in the process of transferring the composition). As a consequence of this displacement at the time of tracing, a figure in the background maritime scene ended up partially outside the painted surface. The subtle differences of approach when doing the architectural features in the background lead us to think that the work in the Museo del Prado is more likely to have been done by Amigoni himself, and that the one in Barcelona, on the other hand, seems to have been worked on more by the workshop. In any case, and bearing in mind that there are no pentimenti or corrections in either of the portraits, we are of the opinion that both may have been made from a third unidentified work, or that the two were conceived with the aid of different templates.