Albert Estrada-Rius

Talking about both sides of the coin is a common phrase that forgets that there is a third with its own name: the edge. This could be defined as the outer and lateral contour that delimits and surrounds the two sides – front and back – of a coin or a medal. This is a part that goes unnoticed but that both coin makers and numismatists take into account. Below we reveal some of the secrets and peculiarities of its history.

The edge of the coin throughout history

Since the coin is three-dimensional we can say that the edge has always existed. We recall that coins appeared independently and almost parallel to China in the 6th century BC. and in the Lydian region of present-day Turkey in the 7th century BC. The pieces made in lands of the ancestors of the King Croesus of Lydia, famous for its richness in gold, are considered the most remote precedents of our coins. The first Lydian coins were nothing more than small electro globules on which a symbol of public authority was hammered.

Emissions from classical antiquity were characterised by thick, convex edges that could obviously be filed.

In anticipation of this eventuality or, rather, as a precautionary response, the contours of the faces were framed with a circle drawn with a continuous or discontinuous line, with pearls or dots that we call knurling. This is an ornamental element that has survived to the present day in the design of many pieces.

The counterfeiting of coins by the system of plating with a sheet of fine metal with a copper core already appears in some Greek pieces. For example, in the hoard from the neapolis of Emporion, conserved in the Museum.

The Romans, in anticipation of avoiding this type of practice, introduced a dent in the edge of a silver denarius issue which is called, precisely because of this characteristic, “serratus” (serrated). This measure was not efficient enough and, as proof, counterfeit specimens are also preserved that imitate it. Therefore, it was soon abandoned. This is probably the first worked edge in history.

Late antiquity and its lack of metal introduced some planchet very fine coins that are characteristic of high medieval issues. This is a peculiarity that is the result of the manufacturing system prevailing at that time and was based on the circular cut of the planchets or discs from thin sheets or metal plates. Once the different coins had been cut and marked with a hammer blow, a stack of coins had to be taken with a tool similar to pliers so that the edges could be struck with a mallet. The aim was to flatten or smooth the sharp cut of the edge to avoid being cut when holding the coins with your hands.

The massive arrival of metals in Europe after the discovery of America caused inflation that led to the manufacture of larger and thicker coins. The edge also grew in proportion and returned to prominence. In some large pieces of silver it would have a considerable thickness. In the lands of the Holy Roman Empire it became fashionable to even take advantage of two large coins to turn them, once emptied, into a small metal box in which to store some beloved and secret image.

One of the most economical and easy systems to counterfeit coins has been the trough from moulds extracted directly from the original pieces thanks to the use of fresh clay. This system allowed the original pieces to be reproduced very accurately with the exception of the edge. In this part the joining of the two halves of the mould was marked and betrayed the fact that the piece was counterfeit. To avoid this, it was necessary to file the edge, which is not always easy to hide from the expert eye. Even today one of the first parts of the coin that numismatists looks at when they have a piece in their hand is the edge.

Copper mould for counterfeiting 8 rals coins of Philip II of Castile, 1556-1598. Museu Nacional.

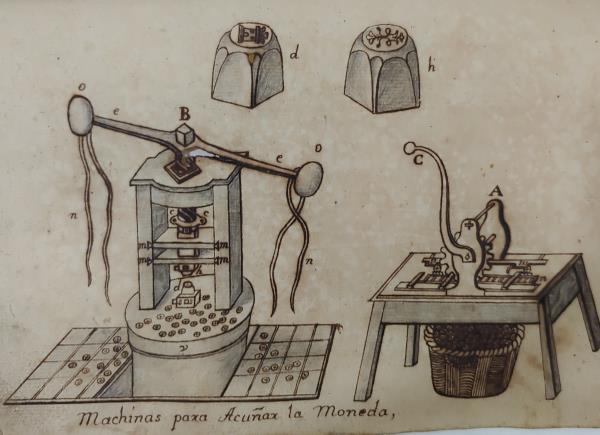

The mechanical manufacture of the coin with hydraulic mills, such as those that can be visited in the Royal Mint of Segòvia, had the immediate effect of producing a better printed coin, with a perfectly circular planchet and a smooth, polished edge. This was the result of minting, with the help of steel rollers, engraved with the negative of the images to be stamped, the metal strips from which the coin had to be extracted with the help of mechanical cutters. It was, to put it colloquially, like making cookies and in the Museum’s collections we also have some examples in the form of a cut or shear. This improvement involved a major blow to the scourge of cutting, filing, or seizing gold and silver pieces.

Around 1680 the French engineer invented the Castaing Machine invented for adding lettering and decoration to the edge of a coin. From then on, the latter bloomed with streaks, grooves, braided spikes, laurel leaf chains, or even embossed inscriptions or incuses. These are the epigraphic edges! The machine has the dual function of giving prestige and ennobling each piece and, at the same time, of serving as an efficient security measure. That is why the milling was usually reserved for gold and silver coins and not copper coins. The edge definitely became the third side of the coin and, as such, was carefully described in the issuance decrees with the other features. With milling, the cutting of coins disappeared forever.

The technological evolution with the minting with flywheel presses was also perfected with the addition of a piece of metal or ferrule that allowed the edge to be stamped at the same time as the obverse and the reverse. The manufacture of coins with automatic presses ensured the careful work of coins until today. The edges highlighted with a strip that allows the coins to be stacked without scratching the engraving of the types of faces are typical of this period.

In recent years, the Euro coins have maintained the tradition of decorating the edges, which, apart from decorating the pieces, have given a new meaning to the third side of the coin by allowing the blind to distinguish by touch the various values of the monetary system. Now, after approaching one of the most discreet parts of the coin and reviewing a lot of specific numismatic terms, all we have to do is to go and get your purse and look at the edges.

Related links

Numismatics Cabinet of Catalonia

Numismatics Guide of the Numismatics Cabinet of Catalonia, Barcelona, 2004

Industrial Revolution and monetary production. The Minthouse of Barcelona and its context, Barcelona, 2013

An industrial heritage revealed: the archaeological intervention of the Minthouse I

An industrial heritage revealed: the archaeological intervention of the Minthouse II

Gabinet Numismàtic de Catalunya