Mireia Capdevila and Francesc Vilanova

Curators of the exhibition The Museum in Danger! The Safeguarding and Organization of Catalan Art During the Civil War, MNAC, July 2021-February 2022

From the autumn of 1934, with the creation of a modern, functional and comprehensive museum of art at the service of the country, thanks to the efforts of figures like Joaquim Folch i Torres, to the dismantling of the museums of Kyiv and other Ukrainian cities, in the spring of 2022.

More than 80 years separate these dates, but with the images of the first days of the war in Ukraine we inevitably went back, following the steps of the people who created museums, preserved heritage and, due to the violence in the contemporary world, had to gather, protect, hide, in short safeguard, not just works of art and material heritage, but also the memory and the identity of national communities, their past and their history.

“…a war in which the destruction of the cultural heritage of the enemy country or people has been used as a means to control it, terrorize it, divide it or completely eradicate it. The goal here is not so much to defeat an enemy army […], but to carry out ethnic cleansing or genocide by other means, and also to rewrite history according to the interests of a victor desirous of consolidating its conquests.”

Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, s.ll., La Caja Books, 2019, p. 10

These are some of the aspects that were talked about in a discussion at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya on 12 May 2022. The activity, organized by the Amics del Museu Nacional in collaboration with the Fundació Carles Pi i Sunyer, was a show of solidarity organized for the purpose of raising funds in order to welcome and integrate refugees and asylum seekers who are coming to Catalonia. Our thanks to all who collaborated: 900 € was raised which has already been given to the Red Cross.

Museums in Danger!

What could connect the experience of a Catalan museum (in fact, the Catalan museum par excellence), to the vicissitudes of the great European museums and centres in the years 1939-1945, the destructions of heritage all over the world (from Yemen to Syria, from Afghanistan to Timbuktu, Iraq or Bosnia, to mention just a few of the best known examples) and, in the end, the spring war in Ukraine in 2022?

The connection is obvious: wars and violence (revolutionary or not, spontaneous or planned and directed). The 20th century, as we said in that discussion, represented a most important qualitative leap for the world, which negates the principle of the moral progress of humanity. In just over 100 years, we have seen images of all kinds of wars and acts of violence, with the destruction of human beings (the dead, wounded, hostages, displaced people, etc.) always at the forefront. Behind them, and the territorial conquests, the destructions of world heritage: books, art, monuments, landscapes, cultural instruments. Everything that constitutes an organized and minimally civilized (cultured) society: the people and their material and immaterial wealth. Robert Bevan explains very well what is behind this war and violence (the sequence could be: conquest of power or a territory, punishment of the civilian or military population; destruction or confiscation of their heritage).

We have the images of the Great War in Europe: Reims destroyed; libraries burned; art lost. However, after that it would be necessary to add the wars and acts of violence in almost every continent in the world. Have we made a balance of the destruction of the European colonial wars? What was destroyed in the war prior to the Second World War in Asia, when Japan began constructing the so-called Asian Prosperity Sphere at the cost of violently conquering much of continental China? We are quite familiar with the list of acts of destruction, theft and pillaging in the Second World War in Europe. We ought to review and see the destruction of heritage in other parts of the world. There was a great deal of destruction. Heritage, in whatever form, has become another instrument of punishment, a hostage in the hands of the enemy.

“Despite the difficulties involved in the safeguarding, the Museum staff (and some volunteer helpers who had joined it) did not desist in the noble undertaking that had been shown to them, moreover without any armed forces to protect them. When force was requested, they received the answer that none was available, so, in the words that were said in those days among those duty bound to serve, it was a case of performing a task rather like trying to “persuade oysters to open”. / In every town […] there was no shortage, in the time of greatest danger, of a small group of distinguished citizens, friends of art, who came to help prevent its destruction. Around the staff of the local Museum (where there was one) or the School of Fine Art (where one existed), volunteers came to help, setting up “Committees” or not setting them up, which made the revolutionaries understand that they were setting fire to the barbarity that they were about to commit”

Joaquim Folch i Torres, 1939

Different installations of the BM damaged by the blitz. As in the early months of the Spanish Civil War in Barcelona, the BM created its safe storerooms in the building’s basement. However, as if following the Catalan experience, some of the collections (this also happened with the National Gallery and the Tate) were moved to storehouses well away from London. Some parts of Wales were particularly suitable for this mission.© British Museum

“At the height of the struggle, anonymous citizens pulled altarpieces, images and holy objects from the flames and, in the midst of the shooting, risking their lives, […] they transferred them to the Generalitat”

Miquel Joseph i Mayol, 1971

Unlike what happened in Europe after 1939, the Catalan case (and the Spanish, for its part, in republican territory at least) had one singular aspect: the safeguarding and organization of heritage was carried out to preserve it, in the first place, from an unprecedented revolutionary outburst, which had begun by destroying all sorts of religious cultural heritage (churches, ecclesiastical archives, museums, religious buildings, etc.), and which could continue with the massive destruction of private (bourgeois) collections or the art of the bourgeoisie (museums like the Museu d’Art de Catalunya). Second, safeguarding it was essential in the face of the fascist aggression (the same that had brought about the revolutionary outburst), especially the bombings of civilian populations and urban centres. And the Museu d’Art de Catalunya was in a particularly vulnerable place, on the mountain of Montjuïc, too close to the castle and the major port installations.

The exhibition The Museum in Danger! The Safeguarding and Organization of Catalan Art During the Civil War aimed to explain a part of this story, with images and works and, above all else, to make a reflection that also goes for Ukraine these days: safeguarding lives and heritage is a state operation, which goes beyond shielding works of art, buildings, along with protecting the attacked citizens. It is a sign of a certain degree of civility, of a minimal cultural and collective sensibility.

Seeing the images of the protection and evacuation of works of all kinds from the Ukrainian museums is like going back to Barcelona at the end of 1936; to the Louvre in the autumn of 1939; to the National Gallery in London, in 1940, at the height of the blitz; to St Petersburg, where the Hermitage was emptied, in the midst of the German army’s siege.

The safeguarding work did not prevent losses of works and heritage. The machinery of war has always been able to prevail over reason and civility. We have seen it everywhere: in Palmyra, in Afghanistan, in Iraq, in the wars in the Caucasus, in the library of Sarajevo. And if the excuse of “collateral damage” could not be used in an act of war, there is always the ideological motivation: the Nazis and fascists burning books; the radical Islamists destroying museums’ collections. And the list would be quite long.

From Cervera, in the summer of 1936, to Lviv, in the spring of 2022. Whether the victim of revolutionary violence or a war of aggression, the cultural heritage (architecture, works of art, popular art, monuments, etc.) has become a target in warfare, almost as important as the control of the territory and the subjection of the communities attacked and regarded as enemies. ©AFB. Autor desconegut / @AP

In Catalonia, between 1936 and 1939, the Generalitat invested a huge amount of effort and resources in preserving the country’s artistic heritage. It did so in different ways and with complementary strategies: from the creation of large storehouses in safe places behind the lines, to the two exhibitions of medieval Catalan art in Paris (Jeu de Paume and Maisons-Laffitte). It was safeguarded, organized, classified, registered, restored, explained and discovered – a policy of managing the collective cultural heritage of the highest order. The pioneering “monuments men” were in Barcelona, Lleida, Manresa, Tortosa, Vic, Tarragona, Girona or Castelló d’Empúries. Afterwards, a few years later, the American “monuments men” would arrive in France.

Protecting the cultural heritage is based on universal laws and techniques. What was done in Catalonia between 1936 and 1939 was repeated in Europe after 1939. On the left, boxes with works of art, perfectly recorded, at Mas Descals (Alt Empordà). On the right, putting paintings in wooden boxes in the Musée du Louvre, in the autumn of 1939. ©Arxiu de l’IEC. Aj. Girona-CRDI (Fons Joan Subias i Galter) / @Musée du Louvre

In Ukraine, in Kyiv especially, functionaries and citizens, academics and professionals, are packing, putting away and protecting altarpieces and paintings, sculptures and pieces of precious metalwork; putting books and carvings in boxes. The images we are seeing take us directly to Barcelona, Olot or Darnius. Their story is our story.

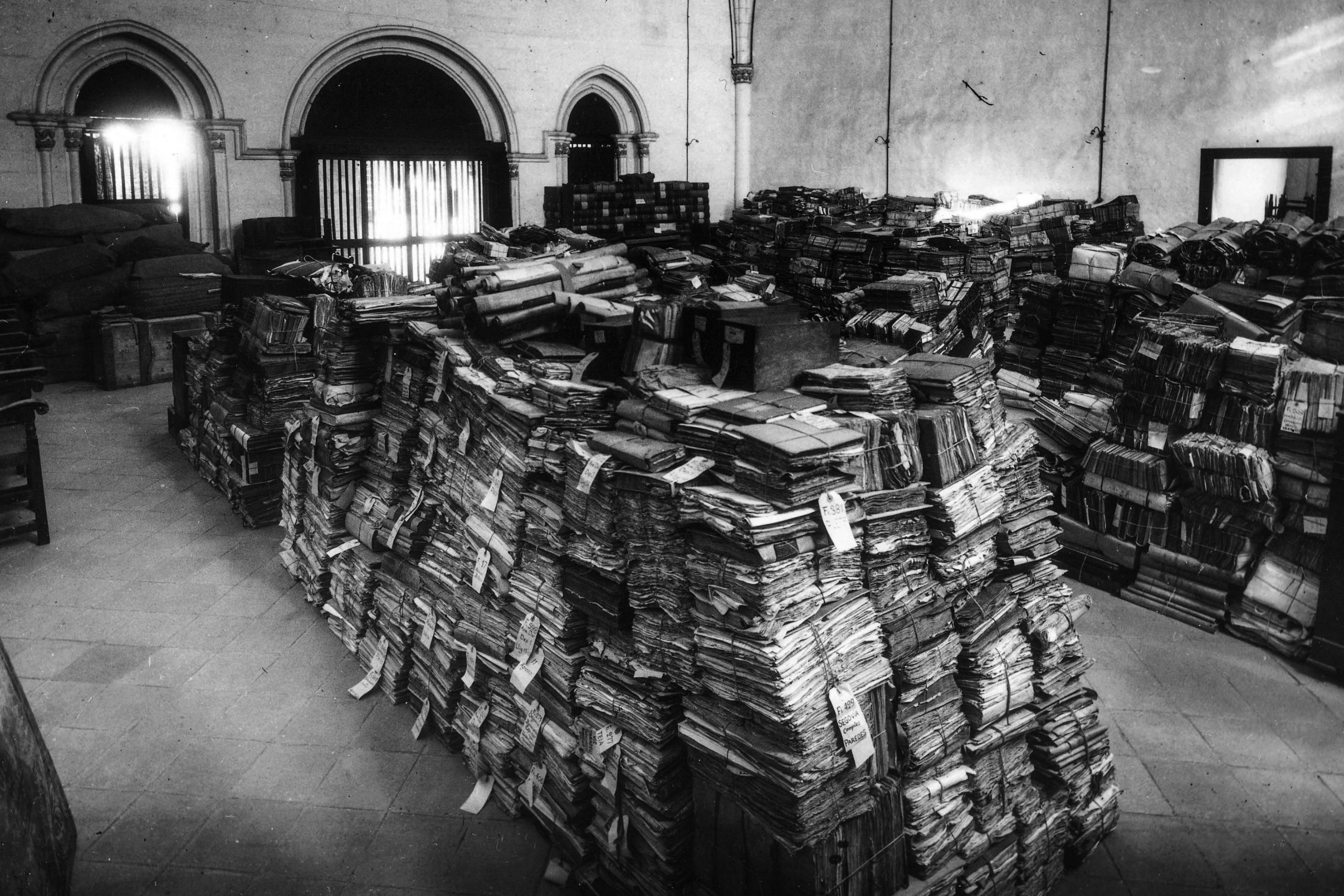

Summer of 1936. Storehouse of books safeguarded in Barcelona. Storehouse of books and other art objects at the University of Cervera. The British authorities could hardly have known about the Catalan experience in safeguarding heritage in wartime and revolutions, but some British experts had travelled to Catalonia in the first months of the war and they may have gained first-hand information. In short, everything that was successfully tried out in Catalonia was replicated in other parts of Europe after 1939. @AFB. Autor desconegut

When the Francoist troops arrived in La Jonquera, on 10 February 1939, the heads of the Servicio de Defensa del Patrimonio Nacional (José M. Muguruza, Luis Monreal, etc.) simply gathered together all the heritage that the Generalitat had collected, put in order, organized and preserved. They did not have to do anything. Later, people like Muguruza and Monreal would lie continually about the fact that the “reds” had stolen, plundered, destroyed, etc. It was the privilege of the victors. We must hope that the Ukrainians do not have to go through this bitter experience. That when they are once again able to unpack their works and put them back in their places in the museums, they can do so with the satisfaction of not having lost the war, not even their personal freedom. Catalonia’s experience in 1939 cannot be repeated in Ukraine. It would be a return to the barbarism of 20th-century European Fascism. Because barbarism, destruction, political and ideological fanaticism, are also part of what has been called European civilization.