Joan Yeguas

In the donation that Enric Batlló made in 1914, there appears a reference to an “Alegoría de la Santísima Trinidad (tres caras en una). Siglo XVII” (Allegory of the Holy Trinity (three faces in one). 17th century). This is an oil on canvas (45.5 x 38 cm) which represents a bust of Christ, dressed in a crimson robe, which appears with three juxtaposed faces; each head has its respective nose and mouth, but the two central eyes are shared by the faces of the ends. In terms of the dating, it could be delimited between 1600 and 1650. The authorship is anonymous and the school is difficult to determine.

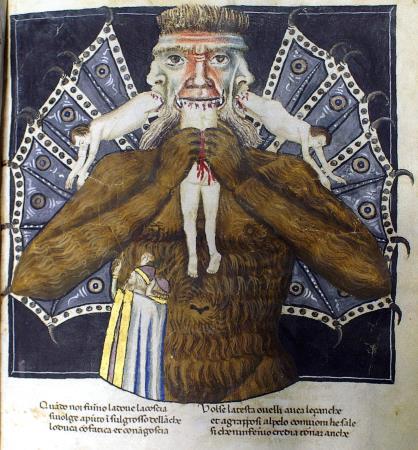

The most interesting thing about the painting is not its artistic quality, which more than justifies it, but the theological argument it represents. The iconographic theme is known as the “Three-faced Trinity” or the “Three-headed Trinity” because it has three identical faces of Jesus Christ (in Latin it is also called vultustriformis or vultustrifons). It has sometimes been referred to as the “Tricephalous Trinity”, but in this case it would be wrong, as it doesn’t have three heads, but three faces. This type of image was used to explain the dogma of the Trinity, a Christian belief that states that God is a single being that is substantiated individually in three people, specifically, the triad formed by God the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The belief is made official in the Council of Nicaea (the year 325); it has caused many controversies throughout history.

Christian iconography of the Trinity

Three-faced Trinity. Anonymous, 17th century. Folklore Museum at the Hellbrunn Palace (Salzburg); and Three-faced Trinity. Anonymous from Mexican school, 18th century. National Museum of Virreinato

The representation of the Trinity in Christian art has been a complex and changing subject. Circumstantially it has been symbolised through a geometric figure, such as, for example, the triangle (even with the eye of providence inside).

Three-faced Trinity with the triangle. Anonymous from a Cuzco school, 18th century. Museum of Art of Lima; and Three-faced Trinity with triangle. Gregorio Vásquez de Arce, 1680. Colonial Museum, Bogota

At other times it has been embodied through the human figure: the incarnation of the Word of God is the Son. Instead, according to the biblical texts, the manifestation of God the Father and the Holy Spirit was always indirect; nevertheless, there are iconographic references where God the Father appears as a man with white hair and a beard and the Holy Spirit is in the form of a dove. Following this thread, the anthropomorphic Trinity has been represented in different ways. One has been the horizontal juxtaposition of three equal figures, which are inspired by the supposed appearance of Jesus Christ; the idea of three identical figures arises in the episode of Abraham’s hospitality (Genesis 18, 1-22), where the patriarch sees three men. Another variant has been the vertical superposition of the “Throne of Glory”, where God the Father is seated and the Son, on the cross (or lying on the lap of the Father, under the influence of the groups of Mercy); sometimes, they also appear associated with the Coronation of the Virgin, forming a triangular group.

In order to avoid Tritheism (the doctrine that makes three gods of the three persons of the Trinity), the three-faced Trinity was used, that is, three faces that shared the same body.

Triple anthropomorphic Trinity. Anonymous from a Cuzco school, 18th century. Museum of Art of Lima; and Triple anthropomorphic Trinity. Anonymous, s. XVIII. Vinseum (Vilafranca del Penedès)

At the beginning of the late Middle Ages the tricephalous Trinity was also used, but it was quickly marginalised, because the three-headed monster delighted on bestiaries. From the end of the 14th century onwards, the three-faced head was consolidated, a solution halfway between Greco-Roman polytheism and Jewish monotheism, founded on visual references of antiquity. For example, the goddess Hecate of Greek mythology, associated with the moon, used to be represented with three bodies or three heads corresponding to three phases of the moon (perhaps for this reason, her statues presided over the crossroads). Three-faced deities were often related to their triple time dimension (past, present, and future), in a way similar to the Roman god Janus, with his face facing back (the past) and the other facing forward (the future). A distant source in Asian art can also be traced, with the “Trimurti” or triple image of Brahma (the creator), Vishnu (the preserver) and Shiva (the destroyer or transformer). The origin is even sought in Welsh, Germanic or Celtic deities of the High Middle Ages, associated with sun worshipping, a star that observes everything; deities who received different names, depending on the region, and who were represented with multiple heads.

Goddess Hecate. Anonymous, 2nd century. National Gallery of Prague; and Trimurti. Anonymous Indian, 9th-10th century. Elephanta island (near Mumbai)

The solution of the three-faced vultustrifonso was appreciated by artists of the Italian Renaissance, as it allowed them to take the model of ancient art. We find this type of representation in different examples: a mural painting in the cathedral of Atrium, carried out by Antonio Martini di Atri around 1400; at the tabernacle of the Court of Merchandise, done by Donatello between 1423 and 1425, outside the church of Orsamichele in Florence; the arch of the Upper Room of Andrea del Sarto, painted between 1511 and 1527 next to the Florentine church of San Salvi, or the painting of the vault of the chapel of Eliodora in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, painted by Agnolo Bronzino between 1540 and 1545.

Three-faced Trinity. Donatello, 1423-1425. Church of Orsanmichele, Florence; Three-faced Trinity. Andrea del Sarto, 1511-1527. Church of San Salvi, Florence; and Three-faced Trinity. Agnolo Bronzino, 1540-1545. Palazzo Vecchio, Florence

In the Hispanic area, there are also some known examples: one of the best known being the Trinity which completed the main altarpiece of the temple of the monastery of Santa María de la Caridad, in the town of Tulebras (Navarra), now preserved in the museum of the same monastery, attributed to the painter Jerónimo Cosida around 1570. Later, in the 17th and 18th centuries, this iconographic typology spread throughout Central and South America.

The three-faced Trinity, from being frowned upon on, to being forbidden

The three-faced and the three-headed Trinity were frowned upon by theologians and other watchers of the Christian canon, considering it a monstrosity of nature. This led to the rejection by Jean Gerson (chancellor of the University of Paris), St. Anthony (archbishop of Florence) or Joannes Molanus (professor at the University of Leuven), among others. In medieval times, this artistic typology also clashed with the polycephalous image of the devil, which was obviously totally antithetical, and which, in the 16th century, was a source of ridicule among Protestants.

Finally, opposition to the representation reached the ecclesiastical authorities, and was condemned on several occasions: first at the session of the Council of Trent dedicated to the cult of the images, produced on 4th December of 1563; and then in a papal bull of Pope Urban VIII, published on 11th August, 1628, in which he asserted that these heretical representations were to be removed and burned. This fact explains the conservation of few copies of this type of iconography, although it did not prevent their survival in rural areas, far from the centres of power. In 1745, Pope Benedict XIV banned it by means of a brief apostolic letter (a pontifical letter setting out resolutions concerning the governance and discipline of the Church), a document known as the “Sollicitudini nostrae”.

Three-faced Trinity. Anonymous German, around 1600. Museum of Tyrolean Popular Art, Innsbruck; and Three-faced Trinity. Anonymous Dutch, around 1500. Sotheby’s New York, 9th June 2011, lot 56

Related links

A bearded women crucified: the Saint Wilgefortis of Andreu Sala

Curiosities of the collection: Renaissance and Baroque

Rethinking the collection: new attributions in the Renaissance and Baroque

Art del Renaixement i Barroc