Alícia Cornet

The Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya preserves among its tombstone collections a slab dedicated to Geralda and Maria, from the old convent of Sant Francesc in Barcelona. These two women were tertiaries, that is, lay people who followed the Third Rule of the Order of St. Francis. There is no documentation on them, all we know is what the inscription on the tombstone reads:

“VI kalendas iunii anno domini Mo.CCCo.VIIo., obiit G(eralda), uxor Berenguerii de Palaciolo, quondam; et eodem anno VI kalendas madii obiit domina Maria, filia eiusdem Geralde, uxor quondam Petri de Civario quondam. Et iacent hic in terra, que prime receperunt terciam Regulam Ordinis Sanctii Francisci. Quarum anime requiescant in pace. Amen”

Thanks to the inscription, we know that Geralda and Maria died in 1307, that they were mother and daughter, that they had been married -Geralda with Berenguer de Palau and Maria with Pedro de Civario- and that they were tertiary women.

Tombstone of Geralda and Maria, 1307, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, (núm. registre 14347)

Who were the tertiaries?

Between the 11th and 14th centuries, a series of transformations in the social, cultural and economic spheres took place in Western Europe. The development of cities led to the emergence of new social classes, such as merchants, artisans and bankers. Universities were born and cities became centres of culture and freedom, with a gradual increase in the mobility of people and ideas. This context also led to a spiritual change. A series of religious movements arose, within and outside orthodoxy, made up mostly of lay men and women who opposed a Church they perceived as powerful and corrupt. Within these spiritual movements we can include the tertiaries, secular ones who, under the protection of the mendicant Order of St. Francis, led a life based on prayer, poverty and the care of the sick.

When trying to delve deeper into the way of life of the tertiaries, a fact was detected in the Catalan documentation of the time that caused confusion: in the manuscripts the term tertiary is used to designate a beguine and vice versa. The two names, tertiary and beguine, were used interchangeably to refer to women who lived very similar lives. Both were lay people who devoted themselves to religious life and alternated prayer with caring for and helping others. They did not perform religious vows, nor did they live in seclusion. They could live alone or in community, and come from different social classes. But despite sharing common guidelines, Beguines and Tertiaries were different religious groups: the former had their origin in the area of Liege (Belgium) and, unlike the Tertiaries, did not have the protection of the Church, they were women who lived autonomously and did not follow any religious order.

Engraving with the representation of a beguine, from the book Des dodesdantz, printed by Matthäus Brandis in Lübeck el 1489

Added to the problem caused by the documentation of the time to know when it refers to a beguine or a tertiary, was the fact that throughout the fourteenth century a significant number of beguines were forced to adopt the Rule of the Third Order of St. Francis. The Church’s distrust of these women who lived independently of male and ecclesiastical control grew and in order to protect themselves from possible accusations of heresy — as happened to Margarita Porete, a young French beguine burned at the stake by a heretic — they had no choice but to adopt the Rule of a Third Order.

Tertiaries and beguines in the city of Barcelona

Geralda and Maria are the oldest tertiaries documented in Catalonia. As already mentioned, all the information that is known is that which can be read in the inscription on the tombstone. Fortunately, we do have documentation of other Beguines and Tertiaries who lived in the city of Barcelona during the 14th and 15th centuries. Sister Agnès, Sister Sança, the Portuguese Agnès and Brígida Terré, are just some of these women who dedicated their lives to helping and caring for others.

- Sister Agnes

In a document dated 1328, preserved in the Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, King Alfonso the Benign refers to Sister Agnes as a woman dedicated to the contemplative life who lives near a leprosy hospital in Barcelona, where possibly the beguine cared for the sick. In this document, the king orders the mayor of the city to expel from the neighbourhood anyone who bothers Sister Agnes while praying. With this document the consideration in which the beguines were held in the city is made clear.

- Sister Sança

She was a Franciscan Tertiary documented at the end of the 14th century in Barcelona. In 1393, King Juan I gave permission to Sister Sança to bury or have buried in a sacred place the bodies and bones of prisoners hanged by justice once they had fallen from the gallows of the city. A royal privilege that once again confirms the social work that these women carried out and how it was valued, even by royalty.

- Sister Agnes, the Portuguese

She was another of the Beguines who enjoyed great prestige among the inhabitants of Barcelona. Documented in a house near the Monastery of Montalegre at the beginning of the 15th century, Sister Agnes was a counsellor for members of the court, a mediator in conflicts and in charge of educating exposed girls.

- Brígida Terré or Brígida Terrera

She was a young woman from the Barcelona bourgeoisie who led the house of beguines of Santa Margarida, located next to the hospital of lepers of Sant Llàtzer.

Brígida Terré came to live in Santa Margarida most probably around the year 1418. The beguines grew throughout the 15th century and became a female community, known as the Terreres, dedicated to assisting the lepers of the hospital of Sant Llàtzer, instructing poor and exposed girls and burying, or having it done, the corpses of those hanged in the gallows of Barcelona, after the tertiary sister Sança obtained this license from King Juan I.

At the service of the deceased

One of the main tasks that these women carried out, and for which they were best known, was to take care of the deceased. They performed a series of actions related to death: they cared for the deceased, guarded, washed and wrapped the deceased, guarded the coffin to the cemetery and even mourned. They were present at Masses for the soul of the deceased and accompanied the family at all times.

In the Middle Ages there was a great fear of dying without saving the soul. For this reason, the bourgeoisie and nobles left a generous donation in their wills to the priests so that they could pray for their souls. At a time when beguines and tertiaries were also involved in these tasks, they became recipients of numerous testamentary legacies. Thus, for example, Agnes of Portugal, mentioned above, was the beneficiary of several testamentary donations in exchange for praying for the souls of the testators.

History of the tombstone

The tombstone comes from one of the cloisters of the convent of Sant Francesc in Barcelona. Opened in 1276, the monastery was a large architectural ensemble that stretched from the current Plaça del Duc de Medinaceli to the Rambla.

The convent of Sant Francesc was set on fire, along with others, on the night of July 25, 1835, the day of Sant Jaume, and two years later, completely demolished.

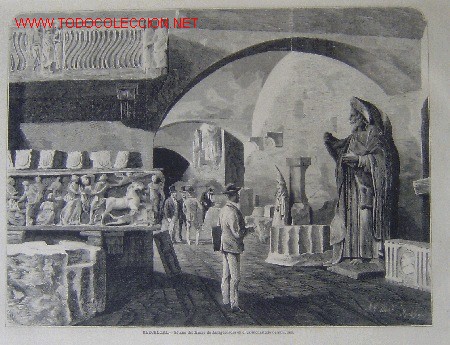

The Museum of Antiquities in the convent of Sant Joan de Barcelona. The Spanish and American illustration, nº. XLVI, 8th December 1873, p. 744

Pròsper de Bofarull, president of the Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres and head of the Arxiu de la Corona d’Aragó, promoted the collection of archaeological remains from these burned and abandoned convents for the purpose of founding a museum of antiquities. These objects, including the tombstone of Geralda and Maria, were joined by others from private collections. In October 1844, the museum was inaugurated in the convent of Sant Joan in Barcelona. Its collection, which initially consisted of Roman and medieval tombstones, architectural elements and tombs, increased over the years. With the return of the convent to the nuns in 1853, it was necessary to find a new space to house the museum. Finally, the collection was moved to the Gothic chapel of Santa Àgata.

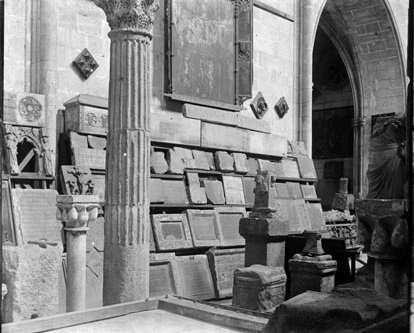

Chapel of Santa Àgata, Barcelona, 1915-1925, National Archive of Catalonia. Authors: Ramon Claret / Joan Bert

The museum would be inaugurated to the public on 15th March, 1880 under the name of Museu Provincial d’Antiguitats. The conservation and cataloguing tasks of the archives, which historian Josep de Manjarrés had initiated at the convent of Sant Joan, would culminate with the publication of a catalogue of 1888 by Antoni Elias de Molins, director of the museum. In this catalogue, the tombstone of the two third parties appears with the registration number 924 and the following description:

“Lápida de mármol. En los lados tiene dos escudos cuartelados en cruz primera y cuarta con un castillo y segunda y tercera con una concha. En el centro de la parte inferior tiene el signo agnus dei”. (Marble tombstone. On the sides it has two shields quartered in a first and fourth cross with a castle and the second and third with a shell. In the centre of the lower part it has the sign agnus dei)

The tombstone remained in the Museu Provincial d’Antiguitats until 1932, when it entered, along with the rest of its collection, the Museu d’Art de Catalunya, installed in the Palau Nacional de Montjuïc.

The purpose of this article is to make known and highlight the figure of these women who carried out important social work throughout European cities during the late Middle Ages. They welcomed the poor, cared for the sick, the dying, their dead bodies and their souls. They were counsellors, mediators in conflicts and trainers. Women who dedicated their lives to helping others and of whom, unfortunately, we know almost nothing.

In memoriam of my great friend Esther Torres

Related links

Catalogue of the Museo Provincial de Antigüedades, Antonio Elias de Molins, Barcelona, 1888. (PDF in Spanish)

CLAUSTRA. Atlas of feminine spirituality in the Peninsula Kingdoms. Institut de Recerca en Cultures Medievals, IRCVM, Universitat de Barcelona.

Les beguines: llibertat en relació, Elena Botinas Montero and Julia Cabaleiro Manzanedo (DUODA, Centre de Recerca de Dones)

Botinas i Montero, E., Cabaleiro Manzanedo, J., Duran i Vinyeta, M. dels À., Vinyoles, T., Les Beguines: la raó il·luminada per amor, Barcelona: Publicacions de lʼAbadia de Montserrat, 2002

Sant Antoni i Santa Clara de Barcelona: origen d’un monestir i configuració d’un arxiu monàstic (1236-1327), Núria Jornet i Benito, Universitat de Barcelona, PhD thesis, 2005 (PDF)

Documentació