Elena Llorens and Eduard Vallès

Following last week’s post, in which we reported on the main new items that visitors will find in the refurbished space “Art and the Spanish Civil War” of the collection of Modern Art, today we will focus on the important collection of works from this period preserved by the Museu Nacional, close to 270 pieces, without which it would not have been possible to tackle a refurbishment of such magnitude. The most repeated question these days is: why does the Museum have all these works from the Civil War?

A collection hidden for forty years

In the mid-1980s, the Museum of Modern Art in Barcelona —the art collections of the 19th and 20th centuries which were incorporated into the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in 2004 under the Museums Act approved in 1990— undertook the revision of its collections with a view to the publication of the catalogue of the painting collection. That revision consisted not only of cataloguing the pieces but also, in some cases, of locating them in the different municipally owned facilities in which it was stated that they had been deposited throughout the history of the museum. In the storerooms of the Palau Nacional, then home to the Museu d’Art de Catalunya, several paintings belonging to this collection were also found and documented. They must have been stored there since the end of the war, when it was decided to segregate the modern collections of the Museu d’Art de Catalunya, inaugurated in 1934, to form an independent museum in the old Arsenal of the Parc de la Ciutadella. However, the most surprising fact was to find a set of works based on the theme of war, and more specifically, the Spanish Civil War, which had literally never seen the light of day. How was that possible?

Fernando Briones, Allegory of the execution of Federico García Lorca, 1937; Amado Oliver, After the bombardment, 1937

It is not known for sure how, when and why these works had arrived in Montjuïc, nor why at that time they had not yet left the place where they had been “hidden”, taking into account that ten years had passed since Spain had left behind the dictatorship, a circumstance that deserved several criticisms at the time. On the contrary, it is easy to imagine that they were hidden for more than forty years in order to preserve them from possible destruction, as they were all the work of artists committed to the Republic: Alberto Sánchez, Horacio Ferrer, Manuel Ángeles Ortiz, Antonio Ballester, Emiliano Barral, Antonio Rodríguez Luna, José Bardasano, Juana Francisca Rubio, Salvador and Pitti Bartolozzi, Fernando Briones, Ramón Puyol, Enric Climent, Gregorio Prieto,Ramón Gaya, Helios Gómez, Apel·les Fenosa, Francisco Mateos, Eduardo Vicente, Josep Viladomat, Ginés Parra, Arturo Souto, Santiago Pelegrín, Miguel Prieto, and a long etcetera of painters, sculptors, graphic artists and engravers, some of whom being very unknown.

José Antonio González Ballesteros, ¡Compañeros!, 1936; and Ginés Parra, Masses-summary, c. 1937

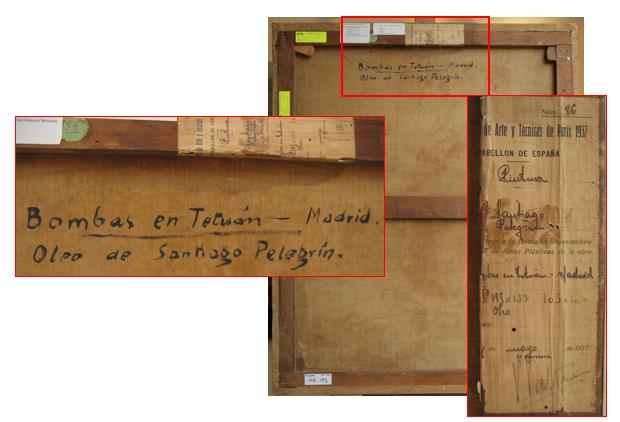

Juana Francisca Rubio, Hero, c. 1937; and Santiago Pelegrín, Bomb in Tetuan (Madrid), 1937

In any case, this fact was soon celebrated and most of the works were exhibited publicly in the exhibition entitled Art against the war, which took place in 1986 at the Palau de la Virreina in Barcelona, curated by Pedro Azara. And the following year, the then Centro de Arte Reina Sofía exhibited a very substantial part of this collection in an exhibition in Madrid dedicated entirely to the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 Paris International Exhibition, whose catalogue, signed by the curator, Josefina Alix, is today still a reference for the study of this crucial episode for modern Spanish art.

The backs of the paintings, the key to unraveling the origin of the works

As a result of the research carried out for these two exhibitions, it was possible to clarify some of the unknowns that had hovered over the works and their respective authors at the time of their discovery. And, what is more important and less known: the presence of two different label models on the back of many of the paintings allowed to establish the origin of the works and, consequently, to shed light on a substantial part of their history and, in return, to begin to work out why they had ended up in the storerooms of the Palau Nacional.

The inscription bearing the first model of label, “Exhibition of Art and Techniques of Paris 1937 / Spanish Pavilion”, left everyone speechless as it put an end to a story that had been in suspense since 1939; for more than forty years it had been believed that the works that had participated in the Plastic Arts section of the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris International Exposition of 1937, inaugurated on 12th July, they had been irretrievably lost: either they had been destroyed by who know who or when, or else they had never returned from Paris. The fact is that many of the participating artists lived for four long decades wondering what had become of the works they had one day selflessly sent to Paris to help show the world the excellent level that Spanish culture enjoyed under the republican regime and denied, in passing, the distorted news spread by the insurgents. Some of them died without knowing the end of the story; others, still alive in the mid-1980s, were able to recover their works, deeply moved; and, still, the heirs who requested it, had the opportunity to recover what was rightfully belonged to them. In total, some sixty works were returned to their rightful owners, some of which can currently be seen in other public collections in the state, such as the iconic Madrid 1937 (Black planes), by Horacio Ferrer , at the MNCARS.

Miguel Prieto, Espigolaires, c. 1937; and Fernando García Alegría, Virgin in front of her dying son, 1937

The research carried out by Josefina Alix was decisive in putting all the pieces together: the works were sent to Paris from Valencia, where in the spring of 1937 the Government of the Republic was installed and where an ex professo commission created had been charged with the selection of the pieces; when the pavilion was dismantled in the spring of the following year, the trucks that returned to Spain with all the material stopped in Barcelona because, apart from the fact that the Government had been forced to move there in the face of the advance of the insurgent troops, ground communications with Valencia were cut off. It is logical to think that artists from Valencia and other parts of the state who had been selected found it materially and logistically impossible to go and collect the works; the war was advancing relentlessly, and the end was getting closer … We do not know if, from the trucks, the works went directly to the Palau Nacional or if they first “slept” in another deposit in the city; nor do we know who gave the order to move them, or who to hide them for so many years. Given the repression that was unleashed from 39, it was doen in a very holy way. Thanks to this, today we have a very accurate picture of the role that the visual arts played in the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris Exhibition.

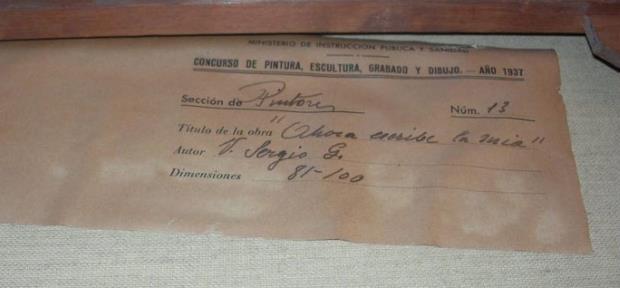

The second label, with the inscription “Ministerio de Instrucción Pública y Sanidad / Concurso de pintura, escultura, grabado y dibujo – Año 1937” (Ministry of Public Instruction and Health / Painting, sculpture, engraving and drawing competition – Year 1937), allowed another important episode to be reconstructed for Spanish art in times of war, at the same time it definitively established the origin of the other major set of discovered works. Let’s allow the administrative language of the time to inform us of the reasons that led the Ministry to call this competition in September 1937: “The need to collect the plastic exaltation that motivates the heroic deed of the Spanish people, scattered today in partial manifestations, to keep alive and with a sense of continuity our artistic tradition, and to ensure that the many facets of the moment can have adequate impact, moves this Ministry to worry about the situation of our artists, seeking the necessary stimulus and help for their creations. To this end, the Ministry of Public Instruction and Health, at the proposal of the General Directorate of Fine Arts, calls a wide competition of painting, sculpture and engraving […] ”.

Beyond the goals that were pursued, which we will not assess in this text, what is interesting here is to highlight the fact that the rules of the competition foresaw organising an exhibition with the selected works, as well as a series of financial rewards for the winners. The exceptional historical circumstances meant that the periods for presentation were extended until December and that the Ministry finally chose to convert the exhibition of the selected works into the first of a series of Quarterly Exhibitions that, unfortunately, did not go on to have any continuity. The exhibition was successfully inaugurated in August 1938 at the Casal de la Cultura in Barcelona (it should be remembered that the Government had been installed in Barcelona since the spring), and among the winners were El Madriles by Josep Viladomat and the Bombardment by Enric Climent, works currently on display. But there were many more artists who competed, and it is clear that most were not able to go and collect their pieces once the exhibition closed. The large number of pieces stored in the Palau Nacional from this competition and the subsequent exhibition certify this.

Apel·les Fenosa, Lleida, 1938; and Enric Climent, Bombardment, 1937

Francisco Mateos, Night, 1937; and Arturo Souto, New family, 1937

History wanted, therefore, that around the same time (summer of 1938) in Barcelona a set of works to be gathered together with a theme mostly of war and various origins, but with a common denominator: its open anti-fascism . It is not surprising that from January 1939 they had to be tucked away in a safe hiding place.

Related links

The Spanish Civil War at the Museu Nacional: New works, new artists

New rooms Art and the Spanish Civil War

Civil War, art, conflict and memory

The endless war. Antoni Campañà

Antoni Campañà. The tensions of a gaze (1906-1989) [Online exhibition]

Art modern i contemporani