Milena Pi

Historical and legendary events are interwoven in the figure of Saint Eulàlia, whose saint’s day we are celebrating this week. We thought this would be a good opportunity to take a closer look at the historical sources, the origins of her cult, and the symbolism that this relic has for Barcelona and the later institutional development of the Catalan Counties. Saint Eulàlia, martyr and benefactor, is also present in the collections of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. The article ends with a small selection of works and a review of the iconography.

The search for relics

In the late ninth century, Bishop Frodoinus of Barcelona proposed to search for the relics of Saint Eulàlia, who had died on the cross five centuries earlier. Barcelona was then in the archdiocese of Narbonne and Archbishop Sigebod was looking for them so that he could have a new church built there, dedicated to her.

As was usual in those days, following the directions of prior rituals, prayers and fasting, Bishop Frodoinus and his clerics «miraculously» found her remains buried near a church dedicated to Saint Mary. This church must have been the present-day Santa Maria del Mar (previously Santa Maria de les Arenes) as it was a Roman tradition to bury the dead along the sides of the roads leading out of the city, namely, outside the walls.

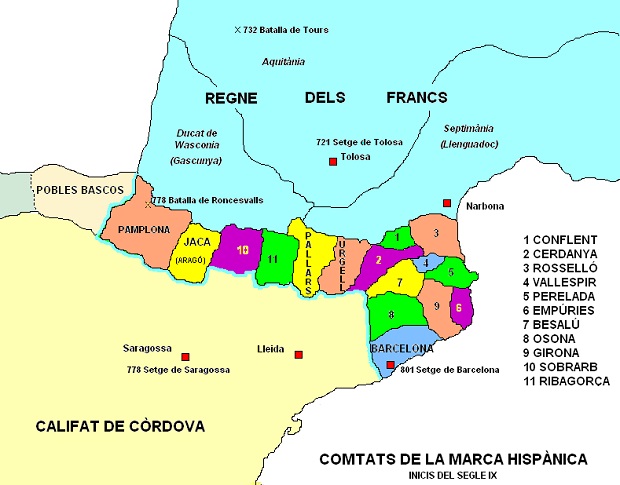

But why was this search undertaken? Frodoinus had been appointed bishop by the Frankish king Charles the Bald, from whom he had also received a large piece of land on the eastern slopes of Montseny and the complex commission of managing the administrative organization of the Catalan Counties, particularly those of Barcelona and Girona.

The political and religious moment was a delicate one, the kingdom of the Franks was defending the Hispanic March from the threat of the Muslims, and part of the pre-eminent orders of local society, who were suspicious, remained loyal to Hispano-Gothic ideas and liturgy. The Visigothic clergy, however, had taken the treasures and the relics and did not want to become part of the new ecclesiastical authority of the Carolingian empire. To strengthen Frankish authority and control in the region, King Charles the Bald endowed the bishoprics with riches, as they were the most representative political and administrative structure in a territory lacking efficient county government.

Charles the Bald died, however, in 877, and that same year Wilfred, count of Cerdanya and Urgell, was appointed as count of Barcelona and Girona. For the first time the counties were not administered by a Frankish functionary, and a line of native governors thus began. Barcelona, Girona, Urgell, and shortly afterwards Vic, would be ruled by Count Wilfred the Hairy (Guifré el Pelós).

To give this new project legitimacy it was necessary to merge native tradition with the Frankish legacy, the Church and the liturgy of Rome. Frodoinus found himself needing to spread his ecclesiastic, political and personal prestige, and that brings to the beginning of this story: the «discovery» (or «invention») of the body of a local saint, already venerated by the Visigothic Church and who implied a continuation of worship, while at the same time it strengthened the ties with the Church of Rome – a union of the past and the present.

After Sigebod gave up his search and returned to Narbonne empty-handed, Frodoinus explored the area near Santa Maria del Mar. When the relic was found, it was translated in a solemn procession to the cathedral in Barcelona. The body was laid in a marble tomb and placed below the cathedral altar. If the saint had been found by someone with the metropolitan prestige of Frodoinus and remained in the city of her birth, her cult would extol the ecclesiastical order inherited from the Franks, and it would consolidate the new institutional system with its capital Barcelona.

As Joan-F Cabestany i Fort says, «We must link the ‘invention’ of the body of Saint Eulàlia to a series of events that originated at that time and which structured the rule of Count Wilfred I and his immediate successors until the middle of the tenth century.»

Well, that’s the history, now for the legend.

- Sarcophagus said to be of Saint Eulàlia, late 3rd century – early 4th century, Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya. Image taken from the blog Tacata. Cultural services.

- Lupo di Francesco, Sepulchre of Saint Eulàlia of Barcelona, c. 1327, Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Santa Eulàlia in Barcelona.

The legend of Saint Eulàlia

The name Eulàlia was originally Greek and it literally means «well-spoken», «eloquent». She is traditionally believed to have lived in the late third century and she died at the beginning of the fourth. She was probably born on the plain of Barcino, in the desert de Sarrià, next to a cypress grove transformed into palm trees by a miracle. She was the daughter of a well-off Christian family, and she is described as a wise, prudent and virtuous girl.

At the age of 12 or 13, in the reign of the Roman emperor Diocletian (c. 244 – 311), an edict was passed that condemned to death all the Christians who refused to offer sacrifices to the idols. In Barcino, the implacable governor Publius Datianus was given the task of carrying it out. Eulàlia secretly escaped from her home to stand before him in solidarity with the persecuted Christian community.

Datianus threw her into the prison in his palace, which according to legend was in the narrow alleyway Volta de Santa Eulàlia. Legend also has it that the sun, ashamed, has never shone inside it again and it is only illuminated on her saint’s day. Eulàlia was required to abandon the faith and, when she refused, she was condemned to suffer thirteen martyrdoms, one for each year of her life.

Place-names in Barcelona and a host of artistic representations in the city’s public places still refer to the saint, her torments and the beneficent power that is ascribed to her. From the hilltop where today we find Baixada de Santa Eulàlia, she was rolled down the slope inside a barrel full of shards of glass and nails. The 13 white geese in the cathedral cloister allude to the ones she looked after.

Pla de la Boqueria and Plaça del Pedró both claim the place where Saint Eulàlia was crucified on an X-shaped cross. Legend has it that in order to hide the girl’s nakedness her hair grew long to cover it. Other versions state that it was the snow that began falling. At the moment she expired, her pure soul came out of her mouth in the form of a white dove.

Saint Eulàlia is the joint patron saint of the city of Barcelona and her feast day is 12 February. Ever since 25 September 1687, and by agreement of the Council of the Hundred, the city’s patron saint has been the Virgin of Mercy (La Mercè).

Bernat Martorell, Flagellation and Crucifixion of Saint Eulàlia. From the Altarpiece of Saint Eulàlia and Saint John, 1427-1437, Museu Episcopal de Vic.

The representations of Saint Eulàlia in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The attributes of Saint Eulàlia are the X-shaped cross and the palm leaf that identifies her as a martyr. She is also shown as a young girl, richly dressed in a tunic and cloak.

At the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya you will find a series of works in different styles and from different periods that will serve as a guide to explain the iconography of Saint Eulàlia, and to mark her celebration we invite you to get to know them. Here we have chosen a few of them:

Saint Eulàlia in the Romanesque art collections

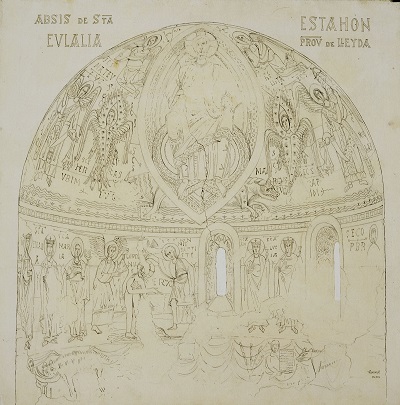

We find the first representation of Saint Eulàlia in the mural painting of the mid twelfth century from the old parish church of Santa Eulàlia d’Estaon, in the Valley of Cardós, Pallars Sobirà.

Inspired by the style of the Circle of Pedret, the iconography of the apse of Estaon presents certain interesting features. The Maiestas Domini reposes on a full circle, a Carolingian reminiscence, and it is surrounded by the Tetramorph. The image of Christ is accompanied by a seraph, a cherub and two archangels. In the half-cylinder there is a depiction of the Baptism of Christ, naked in the river Jordan at the moment he was baptized by John.

Flanking the scene there is a series of female saints. Next to it is the Virgin Mary holding the chalice of the Eucharist. To her right, Saint Eulàlia («SCS EULALIA») the titular saint of the church. On the other side, Saint Lucy and probably Saint Agnes.

At the bottom some deliberately transparent curtains allow us to glimpse a hunting scene: a man with a net, his dog, a wild boar with huge tusks, and another fierce animal. Hunting scenes, very common in Antiquity and assimilated by Christian iconography, must be understood as the struggle between good and evil.

Santa Eulàlia in the Gothic art collections

The Gothic period is noted for the material richness and the profusion of the figurative arts in the different types and techniques. Throughout the collection the figure of Saint Eulàlia reappears more frequently and more prominently.

- Anonymous, Altarpiece of Saint John the Baptist, Saint Eulàlia and Saint Sebastian, second half of the 15th C

- Master of All (Ramon Gonçalbo?), Saint Eulàlia, third quarter of the 15th C

- Lluís Dalmau, Virgin of the “Consellers” , 1443-1445

Although on these panels Saint Eulàlia is represented as a beautiful damsel, dressed in a tunic and cloak and accompanied by her attributes, in the following depictions, by Bernat Martorell, the main theme are some of the tortures that the young martyr suffered.

We first come to three compartments from an altarpiece dedicated to the saint. The scene in the middle shows the flagellation, with Datianus, seated on a throne, looking on. Flanking the central compartment are Saint Michael and Saint Catherine of Alexandria. The assembly of the pieces is modern and does not correspond to the original. In the Museu Nacional there is also a fourth panel dedicated to the martyrdom of Saint Eulàlia on the rack, from the same group. It shows the torturers tearing her flesh in the presence of the prefect, other dignitaries and Roman soldiers.

Bernat Martorell, Saint Michael, martyrdom of Saint Eulàlia and Saint Catherine and Martyrdom of Saint Eulàlia, c. 1442 – 1445

Saint Eulàlia in the Renaissance and Baroque art collections

Josep Bernat Flaugier is the author of this drawing of Saint Eulàlia in which she is once again shown with the X-shaped cross, holding a flower-filled apron. The oral legend as Joan Amades tells it explains this passage for us.

Young Eulàlia was a very charitable girl; people in need frequented her house because she always gave them alms. This annoyed her parents, who often told her off. One day Eulàlia was carrying bread hidden among her petticoats, to share it out, when her father asked her what she was carrying, and she said that she was carrying flowers in it. God worked a miracle and the bread was turned into flowers.

Saint Eulàlia in the Modern art collections

We come to the end of the visit looking at three significant works in which the saint is represented. Firstly, an expressive Martyrdom of Saint Eulàlia by Francesc Torras, c. 1860-1876, where we see Datianus contemplating the scene of the crucifixion.

Secondly, a photograph by Joan Martí of the statue of Saint Eulàlia in Plaça del Pedró, 1874. As was mentioned earlier, this square in the centre of Barcelona is one of the possible places where according to legend Saint Eulàlia died. In the seventeenth century a commemorative monument was erected in her honour. In the photograph we see the original statue by Lluís Bonifaç the Elder and Llàtzer Tremulles, destroyed during the Civil War. Later, Frederic Marès was commissioned with sculpting the new statue that today still crowns the fountain (1951).

Thirdly and finally, we will stop in front of the painting by Aleix Clapés to explain another legendary passage: the Translation of the remains of Saint Eulàlia from Santa Maria del Mar to the cathedral, c. 1890-1902. According to legend, when Frodoinus finally found the tomb of Saint Eulàlia, he organized a cortege to translate her remains to the cathedral, then the church of the Holy Cross. When the present-day Plaça de l’Àngel was created, the coffin was anchored to the ground and it was impossible to lift it. An angel appeared in the sky and pointed to a canon who had stolen one of the saint’s fingers. Only when the relic was returned could the procession continue.

In the Board Room of the Administration Block of Hospital de Sant Pau there is another later painting by Aleix Clapés in which the artist returns to this subject: it is the Burial of Saint Eulàlia, 1921.

Bibliography

- CABESTANY I FORT, Joan-F, El culte de santa Eulàlia a la catedral de Barcelona (s. IX-X), Lambard. Estudis d’art medieval. Amics de l’Art Romànic, IEC, Vol. IX, Barcelona, 1996.

- CARBONELL, E., PAGÈS, M., CAMPS, J., MAROT, T., Guia art romànic, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1997.

- MANOTE, M.R., RUIZ, F., QUÍLEZ, F., MANOT, T., Guia art gòtic, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, 1998.

- PASCUAL I SANPONS (ed.), Robert Baró i Cabrera, Pablo Abella Villar, Cristina Fontcuberta i Famadas, Carme Grandas i Sagarra, Amadeu Carbó i Martorell, Santa Eulàlia, patrona de Barcelona, Ajuntament de Barcelona, Institut de Cultura, Museu Etnològic i de Cultures del Món, Barcelona, 2018.

- REAU, L., Iconografía del arte cristiano, trad. Daniel Alcoba, Ediciones del Serbal, Barcelona, 1995.

- RIBAS GARRIGA, Rosa, Culte i iconografia de Santa Eulàlia i Sant Oleguer a Catalunya. Una proposta didàctica, Ed. Claret, Barcelona, 2009.

Related links

Obra de la setmana #177 – Santa Eulàlia. Amics del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

Santa Eulàlia, patrona de Barcelona. Biblioteca de Catalunya.

Digital Mèdia