Sandra Herrera and Yolanda Ruiz

The exhibition The Colours of Fire. Hamada – Artigas, which can be visited at the museum until 9 January 2022, shows the connection between Catalonia and Japan through the story of friendship and mutual admiration between the artists Josep Llorens Artigas (1892-1980) and Hamada Shōji (1894-1978).

Cultural exchange between Europe and Japan

Relations between Europe and Japan date back to the middle of the sixteenth century. The first European missionaries arrived in Japan during the Muromachi period, but cultural exchange increased notably with Japan’s opening up to trade during the Meiji era and with its participation in the 1867 Universal Exposition in Paris, which gave rise to the appearance of Japonism.

The French capital was the starting point from where the passion for Japonism spread throughout Europe, taking root in Catalonia especially. In Barcelona it became obvious during the 1870s through the programming of shows and the importation of oriental arts and crafts. Furthermore, the participation of Japan in the Universal Exposition of 1888 in the city encouraged interest in Japanese art, and some Catalan artists, like Alexandre de Riquer or Apel·les Mestres, began collecting it. They purchased Japanese illustrated books, some of which are conserved in the Joaquim Folch i Torres Library. We spoke about them in “Japonism and its presence in the museum library”.

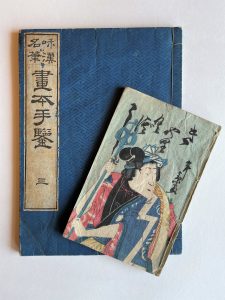

Japanese books stamped “Adquisició Riquer”. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

Japanese books from the Apel·les Mestres Bequest. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

Oliver H. Statler and the publication Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn

Oliver H. Statler (1915-2002) was an American collector specializing in Japanese art. During the Second World War he was stationed in the Pacific. The war ended while he was on leave. Statler asked to rejoin his company, but his request was denied and he ended up joining the civilian service as an army financial administrator in Yokohama and Tokyo during the Occupation of Japan, from 1947 to 1954.

Statler stayed in Japan for four years and he spent his time investigating and writing about the Japanese art that so fascinated him. Shortly after he arrived, he went to an exhibition of contemporary Japanese prints and fell in love with them. As a consequence he met many artists and devoted himself to collecting nearly a thousand prints that are now in the Art Institute of Chicago.

His passion became his study subject. In 1955 he gave a talk at The Asiatic Society of Japan and when his friend the writer James A. Micheler suggested to the publisher Charles E. Tuttle that he should publish a book of Japanese prints, the result was the publication of Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn (Tuttle, 1956), which you can consult in the museum’s library.

![Statler, O. Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn.

Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle Co., [1956]. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library](https://blog.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/Imatge04-207x300.jpg)

Statler, O. Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn. Rutland: Charles E. Tuttle Co., [1956]. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

The book expanded on Statler’s talk and added a selection from among the 300 artists active at that moment who were members of the sōsaku hanga (創作 版画, creative prints) movement. The author was aware that his choice would be controversial, but what he really intended was to motivate readers to follow in the footsteps of this movement all over the world and make their own choice.

Sōsaku hanga

The sōsaku hanga artistic movement emerged in Japan at the beginning of the twentieth century, with the objective of placing the artist in the centre as the sole creator motivated by a desire for self-expression: I draw (自画 jiga), I engrave (自 刻 jikoku) and I print (自 刷 jizuri).

Yamamoto Kanae. Fisherman (漁師 ryoushi, 1904). Woodcut. Image extracted from Wikimedia Commons

Sōsaku hanga shows itself to be opposed to the more collaborative concept promoted by shin-hanga (新版画, new prints), which appeared in the 1910s with the aim of differentiating itself from ukiyo-e, a more commercial art addressed to American buyers. The purpose of shin-hanga is the creation of an ensemble work with the contribution of various professionals in the making of the print: designer, engraver, printer and publisher.

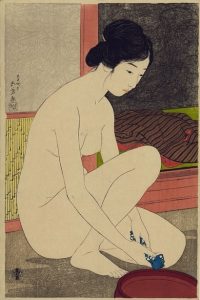

Hashiguchi Goyō. Woman Bathing (浴場の女, Yokujō no on’na) (1915). Woodcut. Image extracted from Wikimedia Commons

But it was not only Europe showing its attraction for Japanese influence. This attraction went both ways and Japan also assimilated some Western influences. For example, the introduction of the exlibris (bookplate), as it is understood in the West, despite the fact that, up to then, marks had been used in Japan that perfectly specified book ownership.

The origins of bookplate print making in Japan

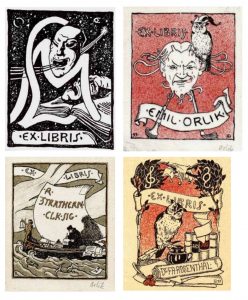

The Japanese passion for bookplate prints dates back to the early twentieth century when the Austrian artist Emile Orlik published four of his works in the journal Myōjō. Shortly after the publication of the prints, Orlik went to live in Japan and during his stay he took the opportunity to do drawings in ink, watercolours, pastels and washes, and to begin collecting Japanese art, including ukiyo-e prints.

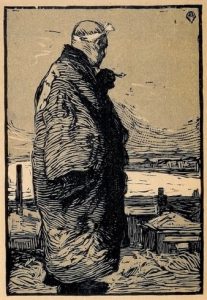

Exlibris created by Emile Orlik and published in the journal Myōjō. Extracted from: Eine Geschichte der Bücherzaichen in Japan. A: Deutsche Exlibris-Gesellschaft

The bookplate fever that was generated in Japan led to the country’s first bookplate association being founded in 1922: Nippon Zohyokai. The goal of the association, wound up for good in 1928, was to publicize the art of the bookplate in Japan and it led to the creation of the first bookplate by a Japanese artist in the 1930s.

In 1933 the Japanese people’s passion for bookplates flourished once again and a new association was created: Nippon Zoshohyo Kyokai, which went the same way as its predecessor and was wound up in 1939. Apart from these associations’ ups and downs, in Japan a very active movement for the popularization of bookplate making has endured and lovers of bookplates began commissioning artists to design their own personal “marks”.

In the midst of this fever, in 1943 Taro Shimo decided to create the Nippon Exlibris Association, an association still active today despite the fact that its founder stepped down from the post of president in 1977 for health reasons. Shimo was succeeded one year later by Kazutoshi Sakamoyo, when the association had by then 1,400 members, including 120 living outside Japan.

Exlibris by Taro Shimo, creator and first president of the Nippon Exlibris Association (1943). Extracted from: http://art-exlibris.net/

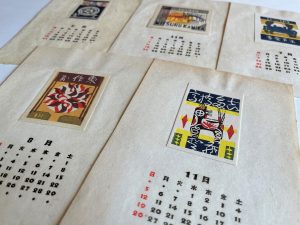

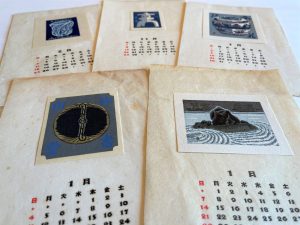

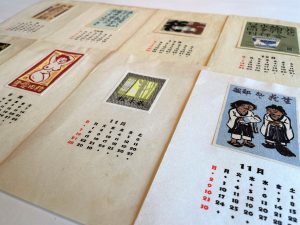

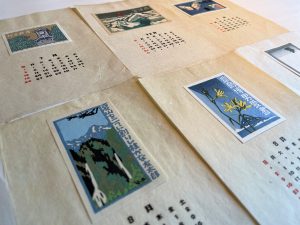

Between 1943 and 2020, the association distributed among its members a calendar formed of twelve exlibris woodcuts designed by different well-known artists. Although they use a simple colour range, the woodcuts achieve brilliant colourful illustrations. The exlibris were printed by hand. For this reason, the print run was very small and membership of the association was limited because their numbers had to be adapted to the production that could be made.

Exlibris by the Nippon Exlibris Association. Extracted from: http://art-exlibris.net/

The artists in the Nippon Exlibris Association

The Joaquim Folch i Torres Library conserves a set of the calendars published by the Nippon Exlibris Association from 1960 to 1980, which contain the exlibris made by about 70 artists. Below, we list the artists whose work is in the virtual exhibition Japanese Exlibris, which you can visit on the museum’s webpage:

- Azechi Umetaro 畦地梅太郎 (1902-1999)

Azechi Umetaro was encouraged by the artist Un’ichi Hiratsuka to delve into the art of the woodcut and his first works were along the lines of the sōsaku hanga (creative prints) movement. Like other artists of his generation, he benefited from Americans’ interest in his work. Oliver Statler included him in the publication Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn (1956) and some years later he was chosen for the volume The Modern Japanese Print: an Appreciation (1962) by James A. Michener.

Exlibris by the artist Azechi Umetaro. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Hashimoto Okiie 橋本興家 (1899-1993)

As a young man he concentrated on oil painting, but in 1936 he started out in the art of the print after attending Un’ichi Hiratsuka’s course on printing woodcuts in Tokyo. He began to be better known in the 1950s, especially after appearing in the book Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn (1956), by Oliver Statler.

Exlibris by Hashimoto Okiie. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Kanamori Yoshio 金守世士夫 (1922- )

He studied woodcut printing with Shikō Munakata, who had moved to the prefecture of Toyama, fleeing from the bombing raids on Tokyo in 1944. In 1952 he was a founding member of the Nihon Hanga-in (Japanese Print Institute).

Exlibris by the artist Kanamori Yoshio. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Kawakami Sumio 川上澄生 (1895–1972)

After graduating at university, Kawakami Sumio spent a year in the United States. When he returned to Japan, he accepted a teaching place in the city of Utsunomiya, north of Tokyo, where he remained for 30 years.

Although Kawakami was little known by other artists in the sōsaku hanga movement, his work was appreciated by those that were part of it. Onchi Koshiro (1891-1955) considered him to be an “incomparable artist” and said that there were few artists that “I would place on the same level as him”.

Exlibris by the artist Kawakami Sumio. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Maeda Masao 前田 政雄 (1904-1974)

In 1923 he met Un’ichi Hiratsuka, the leader of the sōsaku-hanga movement. Although to begin with he worked with oil paint, thanks to the influence of Hiratsuka, of the Yoyogi Group and of the Kokuga-kai (National Artists Association), he learned woodcut techniques and in 1940 he went on to work exclusively making prints. Despite being a typical sōsaku-hanga artist, in many respects he showed the influence of traditional nihonga painting.

Exlibris by the artist Meada Masao. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Mori Doshun 守洞春 (1909-1985)

According to Sekino Jun’ichirō, during the Pacific War Mori Doshun worked on the prints for the reproduction of the roll that tells the story of the failed invasion of Japan by the Mongols at the end of the thirteenth century. Doshun also made brightly coloured prints for the six Ichimoku-shū (Collections of the First Thursday Association) created by the Ichimoku-kay (First Thursday Association).

Exlibris by the artist Mori Doshun. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Seimiya Hitoshi (1886-1969)

He is also known as Seimiya Akira and Kiyomiya Akira. He studied Western painting at the Hakuba-kai school with Kuroda Seiki and woodcut printing with the maestro Goda Kiyoshi. In 1912 he was a founding member of the Fyuzan-kay association, in 1915 of Sodosha, and in 1931 the Nihon no-Hanga Kyokai. His prints of the Fyuzan period were strongly influenced by fauvism and his last works reflected the study of Chinese woodcut techniques.

Exlibris by the artist Seimiya Hitoshi. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Takei Takeo 武井武雄 (1894-1983)

He is considered one of the most important children’s illustrators of the twentieth century in Japan, and his influence is still evident in illustration, manga, cartoons, graphic design and advertising. In 1927 he collaborated in the foundation of the Nihon Doga Kyokai (Japanese Children’s Illustrators Association). He was also a member of the group Ichimoku-kay (First Thursday Association) and he formed an association called Han no kai with Onchi Koshiro. In fact, Onchi convinced Takei to contribute to the Ichimoku-shū (Collections of the First Thursday Association) in 1950.

Exlibris by the artist Takeo Takei. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

- Yashusi Omoto (1926-2014)

His training and his career as an artist were delayed by the Pacific War. He served in the Japanese army but after the war, in 1951, he began studying arts at Meiji University. One of his teachers was Fumio Kitaoka, an artist very close to the sōsaku-hanga movement.

In 1973 he joined the Nihon Hanga Kyokai artists’ association, although he had already been exhibiting with this group since the 1950s. In the 1980s he went to the United States to give demonstrations of the traditional Japanese woodcut printing technique.

Exlibris by the artist Yashusi Omoto. Collection: Joaquim Folch i Torres Library

With this article it has been our wish to present the calendars of the Nippon Exlibris Association published in Japan throughout the twentieth century that are conserved in the Joaquim Folch i Torres Library, and which are part of the virtual exhibition Japanese Exlibris. At the same time, we have explained to you the history that revolves around the publication in 1956 of Oliver Statler’s Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn, of which the library has a copy. It was a very important work for some of the artists who appear in this article because it represented the dissemination of their work, chiefly in the United States.

To end with, we would like to invite you to go to the Joaquim Folch i Torres Library and consult the exlibris of the Nippon Exlibris Association and the work Modern Japanese Prints: an Art Reborn by Oliver Statler, and to visit the online exhibition “Japanese Exlibris” on the museum’s webpage.

Related links

Japanese bookplate collection. University of San Diego

“Oliver Statler” a l’Art Institute of Chicago

“Sōsaku hanga” a Viewing japanese prints

“Shin-hanga” a Viewing japanese prints

Yolanda Ruiz

and

Biblioteca Joaquim Folch i Torres