Francesc Quílez and Aleix Roig

Images of the exhibition. Photo: Marta Mérida

The exhibition The Heartbeat of Nature has been put together from the different elements arising from the artist’s relationship with nature. The connecting thread is work on paper, present in the six sections of the exhibition, in which the nearly 80 pieces are grouped together. These form an exhibition narrative that is characterized by giving visibility to a fairly unknown group, thus making it possible to highlight the collection of the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints (Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya). The selection is completed and enriched with a number of paintings, all of which belong to the Museu Nacional except for four that belong to the Museu Jaume Morera in Lleida and five that are on permanent loan in the Museu Marítim in Barcelona.

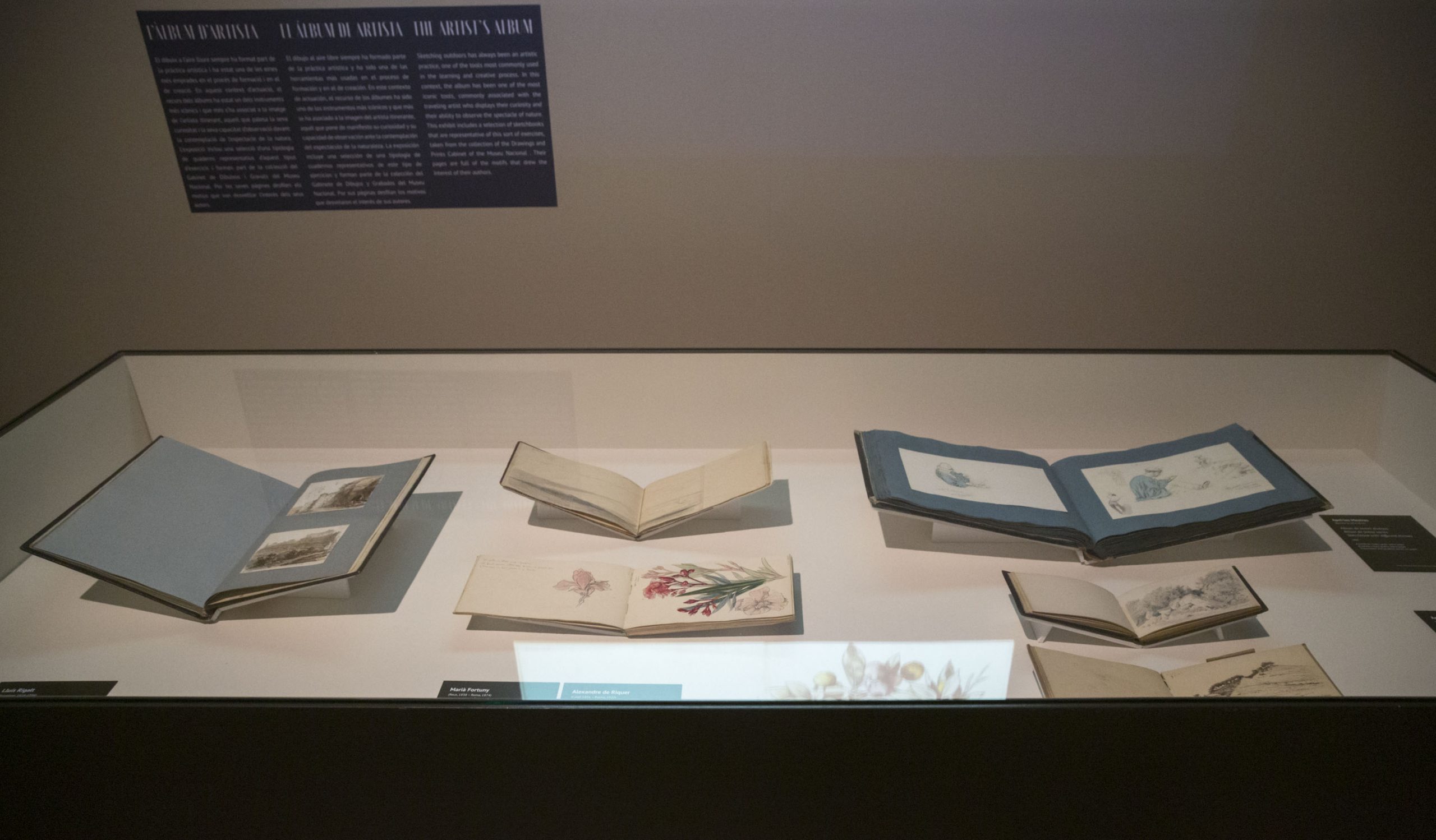

Artist’s album

The visit begins with a selection of a group of albums that prefigure some of the aspects that shape the identity of the different thematic areas represented in the exhibition.

Artist’s album. Photo: Marta Mérida

Although diverse in nature and type, these kinds of albums often contained a series of small notes and sketches that constituted the genesis of a painting made in the artist’s atelier. In other cases, though, they only corresponded to a sporadic artistic urge, or they even served to group together the artist’s own production, to form a collection. Many of them contained pages full of lively, spontaneous drawings that were not meant to be seen by anyone outside their creator’s circle.

They were personal pieces, with a wide variety of types, determined by the interests of the moment. In the case of the depiction of nature, on the one hand we find the delicate attention to detail in Oleander by Alexandre de Riquer (1856-1920) in keeping with the section devoted to organic forms. On the other hand, the immensity of a horizon that is beyond reach, present in Moroccan Landscape by Marià Fortuny, is a foretaste of something we shall see later in the section devoted to natural phenomena. The ruin as a recurring feature in the Romantic imaginary also has its own place in the show, as well as an appropriate prefiguration in this section of albums taken from the works of Lluís Rigalt, Centelles Castle and Castillo de Centellas, who took care to conserve the sketches he made on his travels around Catalonia. Lastly, the drawings of Apel·les Mestres, show the nineteenth-century artist’s attitude to nature, generating a rediscovery of the environment made through direct contemplation and the act of creation, confirming the profile of a personality characterized by the assimilation of all kinds of influences and by perceiving his surroundings with boundless interest.

Apel·les Mestres (Barcelona, 1854-1936). Font del coure / Lying man (Album of different subjects). 1880. Graphite pencil and watercolour on paper. 24 × 65 cm (open album). Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The nature flâneur

This immersive attitude, to which the entire show is indebted and which inspires its entire content, is typical of the figure to which the first section of the exhibition is dedicated: the nature flâneur. He walks in the open air, a gratifying practice in which he enjoys the leisurely exercise of contemplating, gazing aimlessly and stopping wherever he pleases. Just as the urban flâneur does, he remains attentive to discovering, at every step of the way, something unexpected, the epiphany of chance that strikes him and which he uses to nourish his artistic sensibility.

Moreover, he gets away from the hustle and bustle of the big city and immerses himself in the immensity of natural surroundings that help him to formulate aesthetic ideas and the corresponding crystallization in compositions destined to express the heartbeat of nature. Despite being a sketch meant to be both anecdotal and amusing, the watercolour by the architect Josep Oriol Mestres (1815-1895) in which Claudi Lorenzale appears riding on a mule masterfully represents the outings in the countryside already being promoted by Romantic artists. In this respect, it is an iconic image of the appearance of a formative practice, that of working in the open air, which was consolidated, in the Catalan academic system, from the 1850s onwards.

Josep Oriol Mestres (Barcelona, 1815-1895). Portrait of Claudi Lorenzale. 1845. Watercolour and graphite pencil on paper. 19 × 13 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Perceiving also this urge that leads man to discover the riches of the world around him, we find two outstanding works by Jaume Morera i Galícia. The Lleida-born artist is an exemplar of the ideal of the Nature Flâneur, perhaps even more significantly than any other artist in the show, given that he adopted an attitude of defying danger and inclement weather. His urge to depict inaccessible, secluded and dangerous places puts him in a position in which the artistic urge overrides his own protection. The Painter and his Guide shows the reality of a cloudy horizon above a treeless wasteland. The terrain becomes an unknown quantity for the travelling artist, even more marked due to the fog that can be glimpsed. Luckily, he has a guide who accompanies him on this difficult journey, far from the corseted tranquillity within the walls of the studio. Almost as if he were completing the journey described in the previous work, the canvas Peñalara (Sierra de Guadarrama) presents the artist at his destination. These two pieces are also a tribute to himself, and by extension, to the most intrepid travelling artists who did not hesitate when it came to entering hostile environments, withstanding the harshness of the weather and their wild natural surroundings. They were creators who remained impassive with regard to the challenge of capturing a reality that with its grandiosity overawed them.

The quick sketches of Ramon Martí i Alsina also capture this reality based on direct contact and demonstrate the influence of positivist thinking. Free of rhetoric, in his markedly naturalistic view we also find man’s inquisitive immersion in the environment. They are noted for being a very direct, immediate, spontaneous approach: sketches that will have an instrumental function and will help him to transcend the theatrical influence of his predecessors and to adopt a more faithful and realistic register in the depiction of the landscape.

Organic forms

The next section of the exhibition more or less shows how far the process of artistic creation requires the said observation of each and every one of the elements that define a natural space. This rough analysis is closely linked to scientific study, capturing with art the imperfect and unpredictable curves of organic forms. Besides the singular nature of these irregularities, the artist is capable of identifying the common patterns that define a species. The depiction of these archetypes often appears linked to a particular artistic resource, whether in the form of dots, blotches or lines. Therefore, all of these organic motifs end up as the ingredients that make up a landscape, described by each artist based on his own personal language.

This section is one of the ones that best reflect the evolutionary dimension of nature, its power of transformation, its permanent metamorphosis in a creative sense, in which the entire exhibition also shares.

Teresa Lostau (Barcelona, 1884-1923). Salicaria (flor silvestre). Hacia 1921. Lápiz grafito y acuarela sobre papel. 16,5 × 12,5 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

By way of example, there are the austere drawings of flowers by Teresa Lostau (MNAC 107325-D, 107318-D, 107351-D), indebted to an approach close to the botanical, with notes about the species in Latin, and the heterodox coloristic idiom present in Gold and Azure by Joaquim Mir (1873-1940).

Joaquim Mir (Barcelona, 1873-1940). Gold and azur. Circa 1902. Oil on canvas. 111 × 111 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The Box-palette of Marià Fortuny with a Landscape on the Inside synthesizes much of what has been expressed in the previous sections. On an auxiliary support, almost certainly used during outings in the open air, the artist made a small landscape with lively brushstrokes. These are intermingled organically with the blotches of paint present in the same object, as a result of the painter’s activity. The small sketch that can almost be made out also foreshadows much of what is exhibited in the following section.

In this space the desire to create of certain creators, their sudden, unexpected interest in depicting natural phenomena, also emerges forcefully. It is an unexpected discovery that, in the case of Fortuny, takes us beyond reductionist labels, those that identify him as a painter of aristocratic wedding scenes and an orientalist. The exhibition questions this prejudice and allows us to glimpse the importance acquired by the theme of the landscape in his career as an artist.

The next section is devoted to atmospheric and natural phenomena. The direct confrontation with nature through plein air painting placed the artist before an infinite number of variables, generated by different atmospheric and natural phenomena. The phenomena present in the different horizons directly influences the trees, rocks and animals; the perfect symbiosis between the sky and the land emerges through the light. These phenomena, however, can make us feel very small when they unleash all their power. The force of storms overawes even the bravest and the endless fog suggests an uncertain path, as diffuse and mysterious as the one that opens up behind the implacable, dazzling Mediterranean light. In Fortuny we find the most successful example of those who seek to capture this luminosity, typical of Mediterranean latitudes. In this section we discover a large number of works by the Reus-born artist that capture wide-open panoramas of the North African coastline. The great majority of these pieces are watercolours that he used as preparatory studies for the canvas The Battle of Tetouan. The overwhelming brightness that he discovered in Africa was crucial for his art, because although he had already worked in the open air during his time as a student in Barcelona, the experience of Africa represented a point of no return in his permanent quest to investigate and find his own poetic voice. After that he would constantly seek this light on his travels to southern places, far away too from the obligations and the hustle and bustle of Rome, where he lived, whether in Morocco, Granada or Portici.

Marià Fortuny (Reus, 1838 – Roma, 1874). Moroccan landscape. Circa 1860-1862. Watercolour on paper. 50 × 60 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The blinding Mediterranean light is also present in the oil painting Turkeys (Sant Pol de Mar) by Nicolau Raurich (1871-1945). The expeditious touches with which he defines the birds’ plumage recall those used by Fortuny to depict the hens in the work Moroccan Horseshoer. The brightness of the whitewashed wall is however the great protagonist of the work. His mastery is heightened by the thickness of the paint that characterizes the artist’s style. This material effect becomes an accidental trompe-l’oeil, making the depiction of the lime on the bare wall even more realistic

Nicolau Raurich (Barcelona, 1871-1945). Turkeys (Sant Pol de Mar). Circa 1912. Oil on canvas stuck to wood. 54,5 × 53 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Returning to something typical of drawing, the series of clouds by Joan González Pellicer (1868-1908) is also testimony to an approach to nature made based on a language with a marked personal touch. In this case, the Barcelona-born artist opted to depict the sinuosity of the clouds by way of a marked chiaroscuro, emphasizing the sinuousness of the curves, making a series that was experimental in nature. As happens in other productions of clouds present in the show, this is one of the most representative paradigmatic motifs of the constant transformation of nature.

Joan González (Barcelona, 1868-1908). Cloud study. Num. 2. Circa 1904-1906. Graphite pencil and watercolour on paper. 23 × 29,5 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The impossibility of expressing this constantly shifting element once again demonstrates man’s limitations, but also the intrinsic condition of nature itself. Thus, the movement can only be captured with technical means, i.e., photography. However, artistic expression through exercise and painting becomes an attractive construct that constantly challenges the artist’s retina, grouping the different variations together into bodies that despite their verisimilitude have never existed. This paradox is also especially evident in the next section, in which water and above all the sea are the protagonists.

Ultimate land

For the artist, the sea is both an undefined and an infinite place. The ambiguous distance of the horizon and the impenitent power of its water can terrify even the most expert sailors. As we have said, the sea presents a constant variability, impossible to express with pencil and brush, with which only an atemporal approximation can be captured. The marine environment is normally defined by its fiercest aspect. Nevertheless, the depiction of man’s attempt to tame it is also habitual, a quotidian victory that can only be understood through the long truce the waters offer us.

Shipwrecks, storms, views of the sunset and the moon, or the ferocity of the waves; these are some of the Romantic motifs that awakened the interest of artists and which are represented in this exhibition space.

Two works by Jaume Morera present diametrically opposed motifs. On one hand, Villerville Beach (Normandy) describes a sea that, although it does not look particularly aggressive, demonstrates its power through the flotsam and jetsam washed up on the beach. The disturbing darkness of the sky does not invite us to go into the water. On the contrary, The Seine: Vicinity of Le Havre Port of Rouen is one of the few cases present in The Heartbeat of Nature in which we see a natural space apparently dominated by man.

Another notable case is Seascape by the painter Baldomer Galofre (1846-1902). The piece shows an apparently calm sea threatened by a storm that is approaching from the left-hand side. The Reus-born artist recurrently shows dangers in the offing, a form of insinuation that can also be seen in Landscape, in the previous section, in which a faint plume of smoke warns us of a fire.

Baldomer Galofre (Reus, 1846 – Barcelona, 1902). Seascape. Circa 1880-1886. Ink, gouache and conté pencil on paper. 48,3 × 64,8 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The most intimidating aspect of the water can be seen in other paintings, above all the canvas by Joaquim Vayreda, Seascape (Sète, Languedoc). It shows us the wild dynamism of the waves crashing into a small boat. Knowing that the situation will get worse, as determined by the progression of the storm, the sailors have chosen to return to the shore. A second boat is lagging behind them in the background, and its return is even more urgent. Among the things buried in the beach in the foreground we catch a glimpse of the remains of a past shipwreck.

Joaquim Vayreda Vila (Girona, 1843 – Olot, 1894). Seascape (Sète, Languedoc). Circa 1873-1875. Oil on canvas. 24 × 40 cm

The poetry of ruin

Man’s tenacity, along with the desire for survival and his futile clinging to his own mortality, can never vanquish the power of nature that destroys us due to an unfortunate causality or at best to his inevitable deterioration over the years.

Thus, the shipwreck of civilizations, of a longed-for past, and by extension of a radiant youth, also appears represented in the next section, devoted to the nostalgia evoked by ruins.

With its evocative power, the image of the architectural ruin became one of the motifs most visited by the artistic imaginary of the nineteenth century, and it was transformed into an icon alluding to the feeling of fragility of the human condition. The view of this element also contributed to the appearance of an aesthetic school in which the contemplation of a brilliant architectural past, which had been defeated by the destructive power of nature, opened the doors to a feeling of nostalgia, of melancholy, that became one of the distinctive traits of the Romantic artist. The artistic transformation of the ruin facilitated the possibility of reconciling art and nature, freezing the action of the passage of time. Two of the most outstanding pieces in this section serve to demonstrate how the pictorial languages of the period evolved. Thus, the oil painting by Lluís Rigalt, Ruins, shows the chapel of Camarasa Castle in a wholly Romantic light, with the incentive of a certain patrimonial sensibility. In the case of Palace Ruins by Ramon Martí Alsina, stagey artifice is abandoned in favour of a more truthful view that also sets out to give prominence to the environment, in this case the clouds

Lluís Rigalt (Barcelona, 1814-1894). Ruins. 1865. Oil on canvas. 102 × 155,5 cm / Ramon Martí i Alsina (Barcelona, 1826-1894). Palace Ruins. 1859. Oil on canvas. 70,5 × 123,5 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Unlike earlier periods, in which the gaze was focused on the depiction of classical architecture, motivated by the weight of tradition and the fact that Italy had become the place of pilgrimage for the travellers on the Grand Tour, eager to learn about the magnitude of classical heritage, Catalan artists of the nineteenth century directed their observation towards a far closer reality and made the medieval ruin a sign of identity of their effort to recover the vestiges of a monumental patrimony that was scattered all over Catalonia.

Mistery and fantasy

Finally, the last section of The Beating Heart of Nature has mystery and fantasy as its protagonists. The spread of the ideas of the Enlightenment contributed to nature being perceived as a concatenation of natural phenomena inserted in a relationship of universal causality that gave them a rational explanation. Besides this positivist view, based on natural laws, many artists explored the mysterious artistic possibilities offered them by an environment that was reluctant to renounce its evolutive condition. In the works of many of them, nature was interpreted not as a phenomenon, but as the trigger for more lived experiences, dominated by the imagination and fantasy, with the intention of recovering the unity between man and nature that Reason had split apart. Of the artists represented, Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (1817-1870) stands out as the most capable when it came to defining atmospheres evoking these factors.

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (Madrid, 1817-1870). Capricho. Circa 1860. Ink and watercolour on cardboard. 50 × 40 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Despite obviously bringing to mind the work of Goya, Lucas, in his capacity as a draughtsman, was capable of creating a language of his own, contributing a great deal of originality that emerged by way of experimentation and the use of the random blotch technique, highly representative of a formula that was habitual in the period, noted for playing with the factor of chance and spreading the paint over the paper. In any case, the expressive power of the language developed by the Madrid-born artist is noted for the presence of vague elements, ambiguously situated between figurework and abstraction.

Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (Madrid, 1817-1870). Landscape. Circa 1860. Gouache on paper. 40 × 50 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Specifically, in the case of the landscapes it becomes a challenge for the spectator to precisely determine the exact outline of the mountains or the marine horizon. The masses formed by blotches create a dynamic and elusive space, unconnected with the solid tranquillity of the defined instant.

The last artist to mention in this section is Antoni Fabrés. His nocturnal works situate us in threatening unknown places. Despite this apparent sobriety, the artist from Gràcia (Barcelona) also allows himself to be ironic about the Romantic fixation with the unknown. This is demonstrated by the explicit reference to the taste for the funereal, present in Cemetery.

Taking it further, Fabrés caricatured the so-called “Werther effect”, namely, the fascination emerging during the Romantic age with suicide, following among others the example of Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther, and which very often resulted in the materialization of the fatal outcome.

Antoni Fabrés (Barcelona, 1854 – Roma, 1938). Le lac de la mort. Circa 1900. Charcoal and varnished clarion on paper. 80 × 60 cm. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Thus, similarly to the iconic Satire on Romantic Suicide by Leonardo Alenza (1807-1845), Le lac de la mort by Fabrés ridicules this Romantic fixation with suicide. The painter revisits some of the traditional Romantic visual cliches and he ironically disparages their emotional charge and transforms them into meta-pictorial exercises in which an innate talent and a highly virtuoso technical mastery stand out, in which one observes the presence of a layer of varnish that foreshadows Nonell’s famous “fried” drawings. In his case – as in others, Baldomer Galofre for instance, another of the artists that have been an authentic rediscovery – we sense contact with photography, a more than likely use of this reproductive technique to help him or an instrumental resource that would be felt in many of his Italian works, perhaps taken in his Rome workshop.

Beyond this intended causticity, the fact is that Fabrés’ work presents here an idiom both virtuous and ambiguous, based on a personal point of view that describes timeless landscapes for us. The latter maintain a certain vague unreality close to the terrain of insinuations. In fact, nature, understood as the totality of the real, can only be known and depicted partially. Man is thus aware that the environment in which he finds himself is beyond his powers, his mortal transient nature and his understanding. In the face of this irrefutable truth, the artistic urge clings desperately to the futile attempt to express The Heartbeat of Nature.

To know more:

- Check The Heartbeat of Nature playlist on Youtube

- Resources for the visit