Laia Pérez

In the museum we are working on collaborative digital projects to spread the collections internationally. The first digital project of international scope in which the museum participated was Google Art Project, which made the museum’s collections available to everyone through the net. Then came Europeana: Partage Plus and Europeana Photography.

Now, we are present in The Watercolour World project.

The Watercolour World project

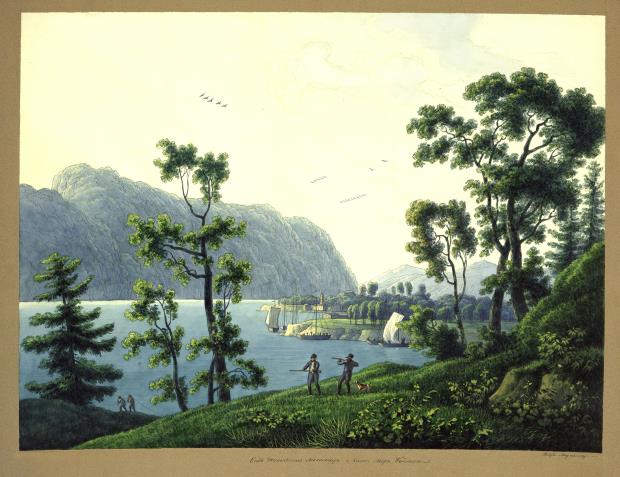

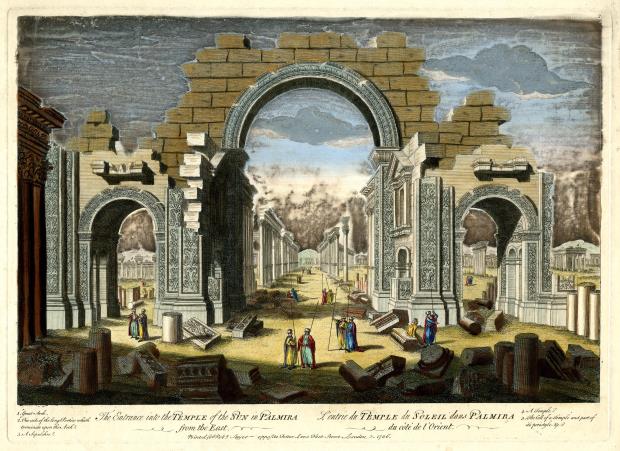

What was the world like in the 17th or 19th centuries? How did people get to know landscapes or monuments, or find out about historical events? Centuries before photography was invented, artists, travellers or naturalists documented the world with a notebook and a box of watercolours in their bags. Over time, with the popularisation of a technique that offered immediacy and ease of transportation, painters and amateurs produced thousands of these first snapshots that captured their gaze on reality while creating extraordinary visual records of the time.

And if all the watercolours conserved in museums, archives, libraries or private collections from around the world were gathered together, would it be possible to reproduce this pre-photographic world?

With this premise, the project The Watercolour World, was born in 2019. An online database of watercolours with the aim of creating the world’s largest pre-photographic collection online. This is a catalogue of digital images, dated between 1750-1900, and geolocated on an interactive world map. The promoter of the project, Fred Hohler, is a former British diplomat interested in the preservation of heritage and who had previously created the Public Catalogue Foundation, an online database of more than 200,000 British-owned paintings and currently Art UK. It is a private initiative with funding from the Marandi Foundation, a non-profit organisation run by the entrepreneurs and philanthropists Javad and Narmina Marandi with the patronage of the British Royal family. In addition, this includes the partnership of the Japanese company Fujitsu, which is responsible for managing the scanning of collections that do not have their own digitalisations.

Explore the collections with a critical eye

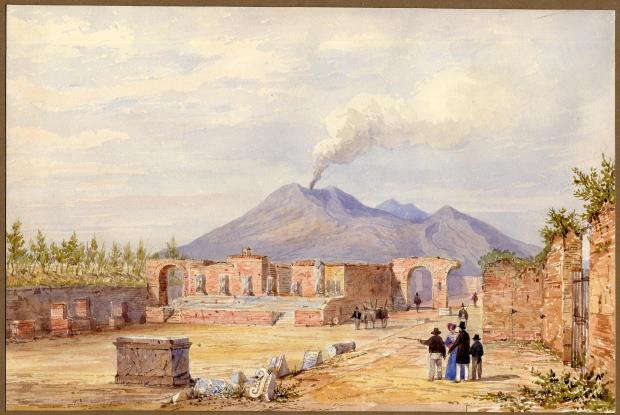

But The Watercolour World is not just an online image bank. Its dissemination strategy combines different goals: the main one is to understand the conservation and dissemination of these works in order to address current issues such as climate change or the destruction of heritage. In this sense, in addition to the possibility of exploring the works through the interactive map, by browsing the collections or using advanced search engines, you can visit thematic albums or monographic articles on various subjects. It is interesting because these are often true graphic chronicles that recount historical events in context with contrasting uses and customs of the time. Thus, you can browse the various eruptions of Vesuvius in Naples, relive the riots of Bristol in 1831 or discover the origins of outdoor fairs, picnics or the evolution of sports such as cricket. Another interesting aspect of its dissemination strategy is to strengthen the engagement with the users by inviting them to help to identify those watercolours whose location remains unknown.

From the outset, prestigious museums and collections from all over the world have joined this ambitious project: including institutions as diverse as the Art Institute of Chicago, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Washington or the Library of Congress, the Rijksmuseum, the Louvre Museum, the Royal Collection Trust, the National Library of France, the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg or the Museo di Capodimonte in Naples, to the National Libraries of Brazil and Peru, among other private collections.

More than two-hundred works available from the Museu Nacional

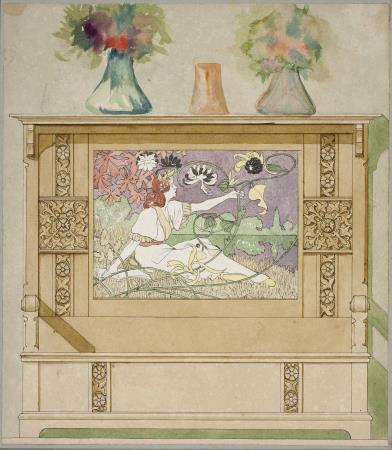

Since May, the Museu Nacional has become the first museum in Spain to participate in The Watercolour World with 281 watercolours selected from the museum’s digitalised collection. From now on, the travel books of Alphonse Delamare, the Moroccan landscapes of Marià Fortuny, the characters of Isidre Nonell, the portraits by Ismael Smith, the reproductions of Romanesque paintings by Joan Vallhonrat or Gaspar Homar’s modernist interior designs are accessible for browsing through the interactive world map.

The participation process is carried out through the online collections of the Museu Nacional and it is from the headquarters of The Watercolour World where they download the data and images from the museum’s website. Thanks to the identifying data that each work generates, these can be linked to the interactive world map through georeferencing. Its website generates a new file for each work with the data provided from the museum’s own collections and with a direct link to the original file of each of the pieces so that the traffic between the two websites is boosted. Furthermore, the images cannot be downloaded from TWW, so there is no problem with image licensing, although they do offer a graphical display with significant increases.

Collaborative projects, a better access to knowledge

But what is required in order to be able to participate and, eventually create digital collaborative projects such as The Watercolour World that propose a broad diffusion of collections, that is to say, knowledge generated from institutions around the world? First of all, it is essential to work on the consistency and enrichment of data, generating a systematised documentation of the collections that strictly follows the international standards elaborated by the benchmark institutions, such as the terminological vocabularies of the Getty Institute, the list of authorities Viaf or Geonames, among others. In this way, more powerful and effective search engines can be developed because if everyone speaks the same language the scope of the results is objectively better. Once the data is ready, you can interrelate with all the projects you want and that follow these guidelines.

![Panorama of Vogel Sang and Cloven Cliff, July, 1818 [i.e. 1819], Frederick William Beechey, 1818. ©National Library of Australia](https://blog.museunacional.cat/wp-content/uploads/Panoramica-de-Vogel-Sang-i-Cloven-Cliff-Noruega-Frederick-William-Beechey-1818.-©National-Library-of-Australia.jpg)

In an interconnected world, participation in projects such as these, in all their aspects, is the path being followed by major international institutions. The strategy, then, is clear, to boost data interoperability in order to reach a larger number and, above all, broader types, of audiences. In this way, thanks to the consistency of data, it is possible not only to participate in multiple collaborative projects, but also in all kinds of virtual applications, such as online databases, interactive maps or dynamic timelines. However it is not just a matter of communicative actions or dissemination of the collections, but thanks to these systems the study and documentation of the works is improved and fostered, as it allows cross-access to other pieces and studies generated anywhere in the world. The pioneering project in this line is the portal Europeana, a European digital cultural heritage platform, funded by the European Commission and currently consisting of some 58,500,000 works of art, books, videos and sound recordings belonging to European Union institutions and which also includes different thematic sub-platforms.

As Fred Hohler explained, founder of The Watercolour World, in an interview, in a globalised world like ours, problems such as climate change with the aggravation of natural phenomena, unfortunately more and more frequent, such as floods, fires, etc. or war or terrorist conflicts, digital preservation of artistic heritage guarantees the conservation and transmission of knowledge which was unimaginable until not so long ago.

Related links

Participating in Google Art Project: opportunity or competition?