Paz Marqués

Madrid, Barcelona and Rome are the venues for a travelling exhibition curated by Andrés Úbeda, deputy director of the Museo del Prado, with the aim of bringing together an extraordinary group of paintings composed of the fragments of fresco mural paintings, which have been removed, and an altar panel. They were originally in the Herrera Chapel in San Giacomo degli Spagnoli, which used to be the Crown of Castile’s church in Rome. The group was commissioned to Annibale Carracci, the great Italian painter, a pioneer of Baroque painting, who did it in collaboration with his assistants. Nowadays, only the panel painting is still in Rome, in the church of Santa Maria in Monserrato degli Spagnoli, while the mural paintings are shared between the Museo Nacional del Prado and the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

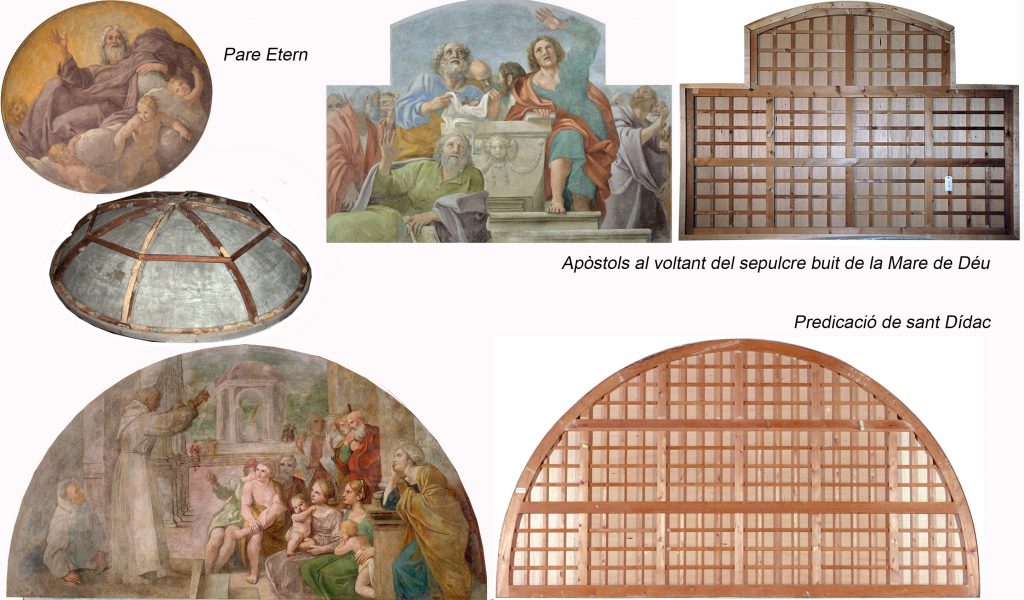

Scenes from the Herrera Chapel, owned by the Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi, on long-term loan to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya since 1906.

In an article in the exhibition catalogue, Mireia Mestre and myself explain how, in the 1830s, the different sized mural paintings were removed and transferred to new supports that since 1906 have been in our collection on long-term loan from the Museu Provincial de Belles Arts, now the Reial Acadèmia Catalana de Belles Arts de Sant Jordi.

A few brushstrokes of context

In 1602, Juan Enríquez Herrera, an important Spanish banker who had moved to Rome, purchased a chapel in the church of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli in Piazza Navona. He was convinced that thanks to the intercession of Saint Didacus of Alcalá his son had been cured, and this was a powerful reason for dedicating the chapel to this saint and decorating it with paintings to illustrate his life and miracles.

Herrera hired Annibale Carracci, an artist born in Bologna in 1560 and already famous, who had been working for many years in Rome, where he had been summoned by Cardinal Farnese. Carracci, who was by then in the last period of his life, made the preliminary sketches and the cartoons for the different scenes; he however developed a nervous disorder that forced him to give up painting, although he directed the work he had been commissioned to do. The assistants in his workshop, Giovanni Lanfranco, Sisto Badalocchio, Domenico Zampieri (Il Domenichino) and Francesco Albani, were given the task of doing most of the painting cycle.

By the end of the 18th century, the Spanish Crown had begun to abandon the church of San Giacomo degli Spagnoli, which was gradually deteriorating, so much so that the paintings in the Herrera Chapel were in a very precarious state. The poor condition of the paintings worried the Catalan sculptor Antoni Solà, who had been living in Rome since 1803. He was well known among the artistic community in the Italian city and was the director of the Spanish artists who had been awarded grants to live and work there. In 1831, on a journey to Madrid to paint a portrait of King Ferdinand VII, the artist told him about the deterioration of Annibale Carracci’s fresco paintings and the great likelihood of losing them if no action was taken to rescue them from there. Back in Rome, the sculptor was sent the funds and permission from the Spanish embassy to coordinate the removal and transferral (terme nou glossari) of the frescoes from the Herrera Chapel. He is, therefore, a fundamental figure in the recovery of these frescoes.

In order to implement this very important plan, the sculptor, who knew the experts in Rome, hired the finest mural painting removal expert: the estrattista (terme nou glossari) Pellegrino Succi (1793 – rec. until 1875). He was the son of Giacomo Succi, also an estrattista, who had earned professional recognition for his life’s work and a monthly salary to work exclusively for the Papal States. Pellegrino had learned the profession and the secrets of the workshop with his father, and when the latter died in 1809, it was he who continued the work even though he was still very young.

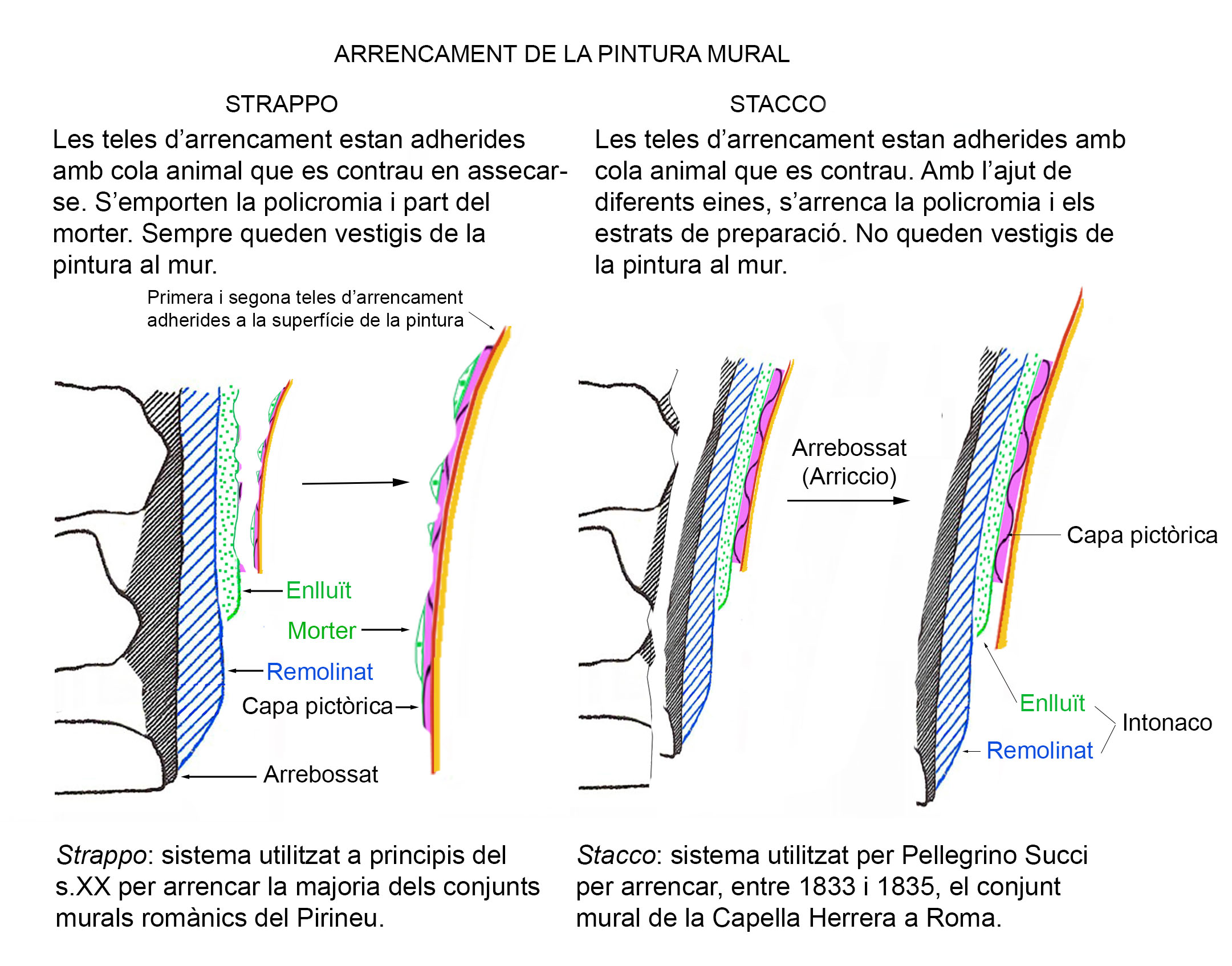

Two of the techniques for removing mural paintings.

Pellegrino Succi removed the mural paintings from the Herrera Chapel a stacco (terme nou glossari) between 1833 and 1835. This technique, different to the strappo which was used in the early 20th century to remove the majority of the groups of Romanesque mural paintings in the Pyrenees, consisted in detaching the paint film with part of the layers of preparation on the wall, intonaco and intonachino(termes nous glossari), and in this way the aim was for the detached fragment to conserve the material qualities of the fresco. The poor condition of the chapel walls and the paintings made removing the scenes very complicated. Proof of this gradual deterioration was the restoration work that had been carried out a century earlier, in 1731, by the Italian painter Sebastiano Conca, who was very familiar with Carracci’s work.

A delicate removal

Pellegrino Succi removed the mural paintings satisfactorily and transferred them to canvas. Let us remember that in order to remove the mural painting the surface had to be cleaned. Once it was clean different pieces of canvas were applied with very hot animal glue. Before the pieces of canvas were applied, it was necessary to fix the surface in order to make the detachment of the polychromy as easy as possible. As the glue cooled it contracted, and with the aid of instruments such as long sharp palette knives the layers of mortar with the polychromy were detached from the wall mechanically. The backs of these layers, once they had been separated from the wall, had to be flattened in order to glue the transfer canvas to them that acted as a new flexible support.

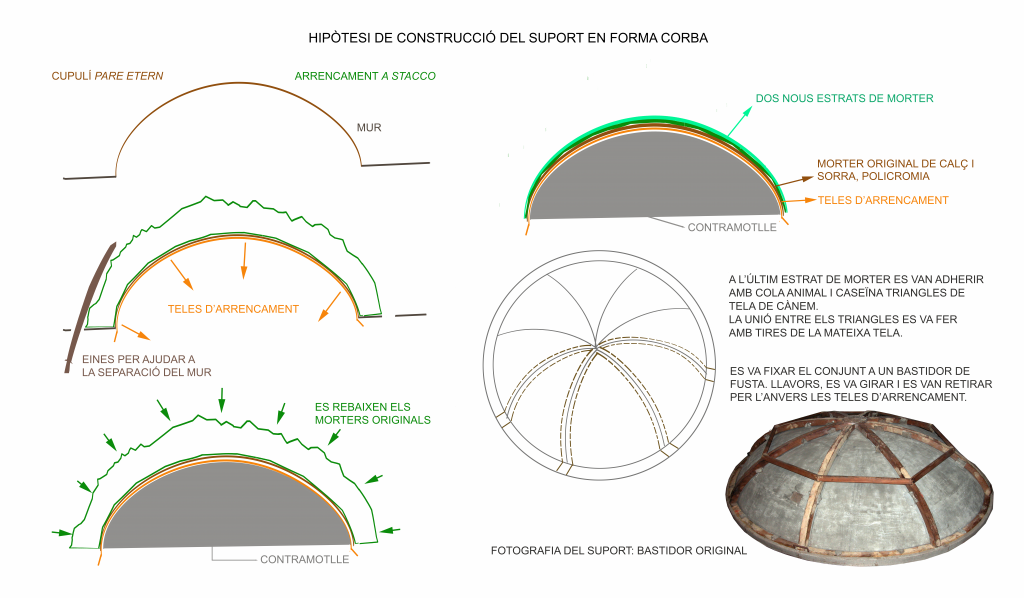

Removal and transferral of the Eternal Father.

Different transfer canvases

The Eternal Father, which decorated the small dome of the lantern (terme nou glossari) in the highest part of the chapel, was the only spherical fragment and it was transferred differently to the paintings that were on the flat walls. Our hypothesis is that the whole fragment was removed and placed on a counter-mould with the same shape, where it was rested face down. Once the back had been flattened, eight triangles of the same canvas were stuck to it, from the centre to the edge of the circumference, adapting them to the curve. The triangles were joined together with eight strips of the same canvas, from the centre of the semi-circumference to the edge.

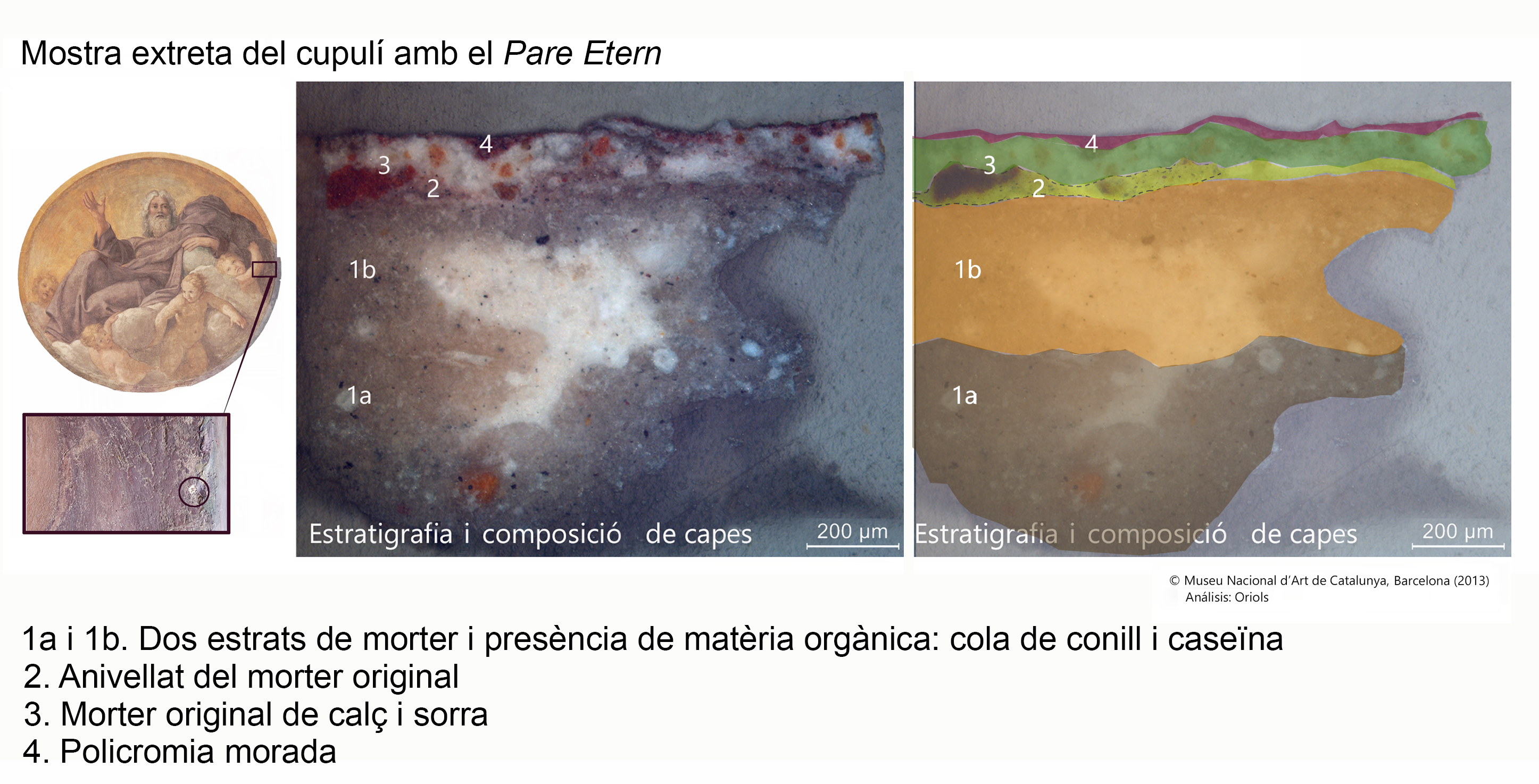

The results of the analyses carried out by the museum laboratory have confirmed that it was levelled with two thick layers, made up of calcium carbonate, plaster, particles of coal and aluminium silicates. Signs have also been detected of the presence of organic matter corresponding to two types of proteins, rabbit-skin glue and casein used as adhesive.

In order to place the transfer canvases on the rest of the flat paintings, Pellegrino Succi had to flatten the back as he had done in the dome. Once the transfer canvases had been stuck on, uncut and the same size as each fragment, he could then proceed to remove, from the front, the glue and the pieces of canvas used to remove them. During the exhaustive study of the fragments at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, we have found only one layer of transfer canvas and it is hemp, in accordance with Succi’s procedure described in the literature, and not the two cotton cloths used by Steffanoni’s team many years later on the museum’s Romanesque mural paintings.

Taken by sea to Barcelona

We know from witnesses of the time that in 1839 the removed and transferred paintings were in Antoni Solà’s workshop in Rome. To make it easier to move them and to keep them rigid they were tensed on wooden stretchers, as if they were paintings on canvas. The paint losses were restored in his workshop and varnish was probably applied.

According to our inspection, at no time were the transferred works rolled up because there are no tiny cracks on the surface of the paintings.

In 1842, Antoni Solà moved to live in the Spanish embassy building in Rome, and there the paintings came to the attention of the Spanish authorities. In 1850 the paintings were eventually sent to Barcelona on board a Sicilian brigantine.

The 16 removed fragments arrived in the port of Barcelona in three boxes. The largest works, in two boxes that were difficult to handle, remained in the Acadèmia Provincial de Belles Arts by order of Queen Isabella II, given the difficulties of transporting them, whereas the third box, with seven smaller pieces, was sent to Madrid.

On 1 January 1906, eight of the nine fresco paintings from the Acadèmia entered the Museu Municipal, in the Palace of Fine Arts in Barcelona, on long-term loan for the purpose of exhibiting them. When the museum moved to the Ciutadella Palace, the paintings were also exhibited, and when it subsequently moved to the mountain of Montjuïc, the directors requested the ninth fragment in the group: the Eternal Father from the lantern. In 1934, to mark the inauguration of the Museu d’Art de Catalunya in the Palau de Montjuïc, and with the new museum layout, the public was finally able to admire the nine fragments from the Herrera Chapel that had remained in Barcelona.

The analyses enable us to distinguish between the original layers and those added during transferral.

Supports and interventions

To date, the flat fresco paintings have been worked on separately at different times. One of these interventions, however, affected all the flat paintings and consisted in changing their supports. We do not know exactly when it was, but the wooden stretchers attached in Rome were replaced by the paintings’ current supports. In any case, this type of support is the same one that we find on all the fragments of fresco mural paintings removed and transferred in the museum in the same period, the 1960s. It consisted of a wooden grid framework to which a plywood board was nailed. It was a rigid support, more homogeneous to receive the fragment of painting and lighter than the type of support with a wood, cloth and plaster structure that was used in the 1920s. The flat fragments placed on this new support were adhered with flour paste without a reversible layer.

The transferral of a scene coming from a flat wall.

The scene from the lantern, due to its spherical shape, continued with the original wooden stretcher made in Rome. The arched ribs do not touch the canvas that is attached to the round base of the stretcher. Some canvas reinforcements join and tense the canvas of the support with the ribs in order to prevent the fragment from moving. They are small canvas rectangles that were gradually torn over the years and were changed at the end of 2019.

The frescoes will be reunited again to evoke the magnificent 17th-century mural cycle from the Herrera Chapel, in an exhibition for which many of the fragments have been restored. It will be an excellent opportunity to savour both the spectacular colours and the technical skill of Annibale Carracci and his assistants and to learn about the vicissitudes of the group of paintings.

Restauració pintura mural