Sílvia Redondo, Mireia Rosich and Íngrid Vidal

On 10 March 2021, to mark International Women’s Day, the activity “Transforming the gaze: the visibility of women artists” was held virtually. The main objective of this event, organized by the museum’s Joaquim Folch i Torres Library and the Art Museums Network of Catalonia, was to learn about, rethink and discuss the place women occupy in museums through a dialogue between the invited speakers and those participating in it.

The idea of this dialogue arose from the present need to establish a review of institutional discourses in order to raise awareness of a reality hidden for a long time in museum storerooms and to transform the way we currently regard these female artists.

The speakers invited to this dialogue were Elina Norandi, Laia Manonelles and the artist Mari Chordà, all women associated with the art world who, through their experiences, spoke to us about the visibility of women artists from different points of view. Moderating the encounter were Mireia Rosich, director of the Víctor Balaguer Museum, and Sílvia Redondo, director of the Joaquim Folch i Torres Library.

The aim of the event was obvious: to improve the visibility of women artists, especially those who are still invisible today, and to transform our gaze in order to change this situation. To achieve this, the Library and the Network came up with a live activity, a dialogue between women from different fields, all of them associated with the art world, who, through their experiences, would give a clear account of the current situation of female artists. And this is how this encounter came about.

Recently, with the commission “Feminism and Identities” created to address gender issues, the Art Museums Network commissioned Elina Norandi to carry out a study of the women artists present in the collections of the 22 museums that currently comprise it.Based on this study the census of women in the public collections of the most important Art Museums in the territory has been obtained. The census will enable us to cross-reference data and consider proposals for the future, not just exhibitions, but also research and interpretation – information that will have to be taken into account in the acquisitions policy.

The event was divided into two main blocks: in the first, the guests made a brief presentation and in the second, guests and participants established an interesting dialogue on the subjects put forward in the presentations.

Bloc 1. Presentations of the participants

Elina Norandi

Elina Norandi is a historian, art critic and exhibitions curator. She has a PhD in Art History, and is a tenured lecturer in Art History at the Escola Superior de Disseny i Art Llotja. She has published a large number of articles, essays and book chapters about the iconography produced by women in modern and contemporary art. She has also shown an interest in the artistic discourses related to issues of gender, dissident sexualities and queer theory. In 2017 she was appointed curator of the Sacharoff Year by the Generalitat de Catalunya’s Department of Culture.

As a result of her first study, Elina explained that some museums, such as the one in Vic, were not included in the census, given that they had no work by women documented. On the other hand, the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, the Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona and the Museu del Disseny had supplied the bulk of the names of women artists. Those in the MACBA were current artists, most of them still working. Other museums had provided contemporary artists, but there were also some from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In the case of the Museu del Disseny, the inclusion of fashion designers had been ruled out, as they would be held back for a second part.

The total number of female artists is 1,249, although this is a provisional figure; many data from the inventories have still to be reviewed and more will almost certainly be added.

It has been possible to draw some conclusions related to the presence of women in museums. For the moment the following have been counted:

- 132 artists present in more than one museum

- 79 in more than two, the majority contemporary

- 36 artists in 3 museums

- 8 artists represented in 4 museums

- 4 artists in 5 museums, who are Lola Anglada, Fina Miralles, Pilarín Bayés and Roser Bru

- 1 single artist with work in 6 museums: Maria Girona.

- 3 women in 7 museums: Esther Boix, Concha Ibáñez and Aurèlia Muñoz.

- the artist most represented, to date, in 8 museums: Maria Assumpció Raventós

It has been possible to confirm that, broadly speaking, the names most present are associated with so-called third wave feminism, female artists who worked in the 1970s. From earlier generations we have only found Lola Anglada and Ángeles Santos. The rest are more contemporary artists, like Glòria Cot, Núria López Ribalta and Eulàlia Valldosera, who are still producing work.

“The study is a starting point. For the moment we have gathered very basic data in order to make this joint inventory. For many of them we do not even have basic data, such as their place of origin or some dates,” Norandi said.

It has also been possible to make a geographical classification according to the data collected:

- More than 500 female artists were born in Catalonia

- 118 were born in the rest of Spain

- 210 are from the rest of Europe (mainly Germany and France, followed by the United Kingdom, Italy and Austria)

- 89 were born in America (45 in the USA and 10 in Argentina)

- 23 are from Asia (11 from Japan, 4 from Israel; the rest are from Iran, India, Afghanistan and South Korea)

- 7 were born in Africa (Egypt and Morocco mostly)

- 1 Australian artist

As for the chronology:

- the great majority are artists born in the twentieth century

- 125 artists were born during the nineteenth century

- 5 artists were born in the eighteenth century, including Angelika Kauffmann and Elisabeth L. Vigée Le Brun

- 2 artists from the seventeenth century, still quite unknown, Claudine Bouzonnet Stella and Maria Magdalena Küssell.

With regard to the artistic languages, painters and sculptors have been recorded, but also photographers, visual artists (including, among others, performance and installations) illustrators, bookplate makers, medal makers, and designers, in the graphic arts and of fabrics and jewellery.

Laia Manonelles

Laia Manonelles has a PhD in Art History from the University of Barcelona and is a lecturer in the Department of Art History at the same university. She has curated different exhibitions and has done research in action art, experimental art and Chinese art, among others. She is the author of the book Arte experimental en China, conversaciones con artistas (Experimental Art in China, Conversations With Artists) and is a member of the editorial committee of the University of Barcelona journal Matèria.

Laia took as a point of departure the work by María Gimeno, Queridas Viejas (Dear Old Ladies), presented at the Museo del Prado in 2019, as an example of a reparative work in relation to the presence of women in academic studies. In Gombrich’s Història de l’Art (The Story of Art), which has been used, in both Art History and Fine Art studies, as a reference book, there were no female artists. Gimeno cut some artists out of the book and replaced them with female artists, placing them in the relevant period, clearly showing that the official account has silenced them. It is not just Gombrich’s book, other women artists have also worked on it. The canon must be reviewed. Teachers have a responsibility to provide a polyphony of voices.

Laia’s genealogy led her to make personal reflections. She considers that Dr Elsa Plaza was fundamental in her education, as she helped to raise her awareness of gender perspective. Plaza showed her both women artists and new gazes when it came to making curatorial proposals. Among other artists, thanks to Elsa she got to know the work of Mari Chordà, Nora Ancarola and Marga Ximénez, who in fact is currently present in an exhibition at the Museu d’Art de Cerdanyola, “From Oblivion to Rebellion, Invisible Goddesses.”

Manonelles said that important progress is being made. For a start, female students are calling for the presence of women artists in study plans. At the university optional subjects have been activated – based on feminist perspectives – like the one by Assumpta Bassas. The Master’s in Advanced Studies in Art History has an Art and Gender course. And, finally, an exhibition of Fina Miralles’ work has just been organized at Casa Elizalde. There seem to be many initiatives. It can also be confirmed that there are more degree, Master’s and PhD studies that place the emphasis on this undertaking to provide visibility. According to Manonelles, all these initiatives are important and very necessary, but structural, in-depth work is also needed. A course on gender would not be necessary if it was completely integrated in the corpus of the different subjects.

Another key issue should also be incorporated in the discussion, reconciliation. Is it real or not at university? How does it affect everyday life? In any case, it is essential to let women artists speak, and out of respect for them, more books and more exhibitions are necessary.

Mari Chordà

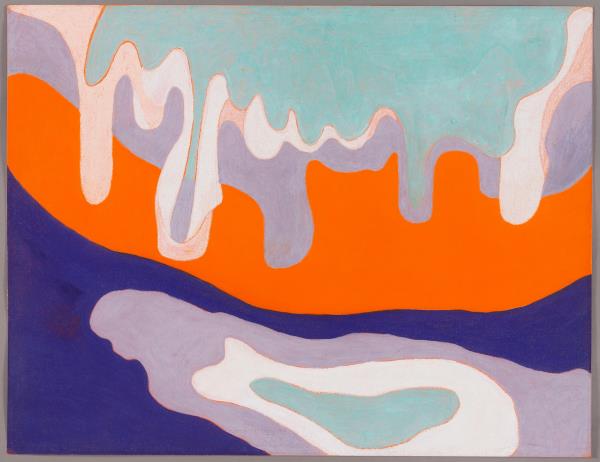

The last to speak was the Catalan artist Mari Chordà, a versatile feminist poet and sociocultural activist, known for being a pioneer in the artistic representation of female sexuality and the experience of motherhood, through lively works, full of colour. She went into exile in Paris for a while and eventually returned to her hometown, Amposta, at the end of the 1960s. Her daughter was born in Amposta and there she also began her intense cultural and feminist activity, founding the Llar d’Amposta. In the late 1970s she took part in the founding of the women’s space LaSal, in Barcelona, and also in the first feminist publishing house in Spain, LaSal Edicions de les Dones.

She has never stopped, and still today she continues with her creations and her sociocultural activism. Her work is present in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, the Reina Sofia in Madrid and in 2015 her work was included in an exhibition at the Tate in London.

The artist said, “For many years I have only worked at home. I had a study in a small guests’ bedroom in Amposta and that’s where I began. I wanted to make one thing clear: how important it is for women to find someone you can trust. I was fortunate to meet Marisol Panisello from Amposta, a figurative painter who used to go to the mountains or the sea to paint. I also became fond of going into the countryside to paint. I took part in art shows. Luckily I came to Barcelona, otherwise I would probably only have done landscapes.”

Chordà stated with satisfaction that many young girls, and some boys too, are enthusiastically joining the feminist movement. Many of them go to Ca la Dona, a mansion in carrer Rupit (Ca la Dona, space for feminist action) that has been made available to them by the present city council, for which they are very grateful. There is a room for exhibitions, and – ever since they were held in carrer de Casp – publications have been made of these; all in all, a lot of work done and, luckily, a lot of young women who have come together.

On several occasions she mentioned her roots in Amposta, of which she is proud, just as, according to her, she was fortunate because her father was not opposed to her studying art, since “Fine Art in Barcelona was old-fashioned at that time.” On a trip to New York, at the Metropolitan she understood the usefulness of having studied Fine Art and of having enjoyed the solidarity of other female artists. She mentioned the artist Soledad Sevilla, since, according to Chordà, women see themselves reflected in each other, and based on this recognition of themselves in others they construct their own identity.

In 1958 l’Olla was opened, in the Terres de l’Ebre, where different female artists got together. The artist regretted that, for many years, the Terres de l’Ebre have not been given due recognition. Luckily, things are changing and there is now a School of Fine Arts in Amposta.

The artist said that, right now, her ambition is to take the time to write, as she is busy with a book of poems.

Block 2: Dialogue

Based on the questions of those in attendance, different issues were raised that we present below.

How have the works arrived in the museums?

Mireia Rosich, as the director of the Víctor Balaguer Library-Museum, commented that this question is not always easy to answer if the admission is not properly recorded, especially if they are pieces from before the twentieth century. She also confirmed that, in the case of the museum she directs, the two women artists that are recorded there personally donated their works to Sr. Víctor Balaguer.

Elina Norandi said that, in effect, some museums have been formed based on the repertoire of collectors and both the Víctor Balaguer Library-Museum and the Abelló Museum in Mollet del Vallès are examples of this. Moreover, in the case of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, it has been confirmed that many works by women were purchased. It was a habitual practice, Elina said, for the City Council to purchase works – by women artists too – at the municipal fine arts exhibitions that were organized on Montjuïc, but also at the Salons that were held every year or two years in the Ciutadella Park, formerly the site of the city’s Modern Art Museum. The City Council had a specific budget for purchasing art and, contrary to what people might think, quite a lot of work by women was purchased; it is for this reason that many women’s names have now been found when compiling the census. What we have to ask ourselves is why these female artists, despite entering museums’ collections, are still unknown today.

Another way that work by women can enter is by donation, whether because the artists themselves decide to make a donation to a museum, or whether the artist’s family does so after their death. Donations, said Elina, are not always as successful as the family would like, since space in museums’ exhibition rooms is limited and the works often end up in the storerooms.

Norandi commented that these data are still being studied, but what she could say is that the majority of the works by female artists in the census have entered collections through purchase. The case of Mari Chordà is a good example of this; the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya admitted 4 works by her, 3 purchased and 1 donated by the artist.

Has it been possible to identify women who signed their work with a male pseudonym?

Historically, resorting to the use of a male pseudonym was, in some cases, the only way to present one’s own work. Other habitual practices were signing with one’s initials, with one’s surname only or simply not signing. Thanks to the study of the different documents, said Norandi, of memoirs and chronicles, but also of letters, we know that many women artists decided not to sign with their own name because they were aware that this detail would work against them. The implications of signing with a woman’s name could affect everything from their assessment in a competition, to the possibility of exhibiting or finding places in which to promote their work.

In the case of the census commissioned by the Art Museums Network of Catalonia, it should be said that it has been compiled from filtered data, aimed specifically at female creators, and it is for this reason that pseudonyms have not been identified.

What is the way to progress towards making women artists visible?

On this point, Mari Chordà stated bluntly that women artists have to do their bit and must be prepared to collaborate in this cause. Chordà referred to the case of the artist Núria Llimona as an example of an artistic legacy that should be highlighted. The female artist’s family is crucial after her death, and therefore, it has to take charge of dealing with museums so that the work can be given the recognition – the visibility – it deserves. Chordà in fact declared that she intends to donate to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya the photographs she has found recently of the ‘umbilicals’ series, some of them whose whereabouts were unknown.

Moreover, Chordà made a case for creative spaces, such as the Llar d’Amposta, the feminist LaSalbar–libraryand LaSal Edicions de les Dones, creations she considers as important as her plastic work.

Laia Manonelles seconded the importance of places for meeting and dialogue, reviving the notion of the ‘pleasure of sharing’ that Mari Chordà suggested. The pleasure, which according to Chordà, is revolutionary, was explained by Manonelles – going back to the words of Elsa Plaza – as the pleasure that is generated through shared moments. Through pooled reflection, from different spaces created with this intention, personal growth takes place. Fieldwork is essential, said Laia, and one must make contact with the protagonists – the creators – whenever possible.

Along these lines, Elina pointed out that, right now, it is crucial and urgent to work with female artists who lived under the Franco dictatorship. It is crucial to hurry up and contact those who are still alive; they are the living testimony of a reality of oppression and lack of freedoms that ought to be gathered as soon as possible. Of course, said Norandi, it is necessary to continue working with the women of the past (women artists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries), but we should urgently collect first-hand accounts to learn about a reality that explains why, still today, there are so many unknown female artists.

Pilar Cuerva, Director of the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya’s Research and Knowledge Centre, pointed out the importance of the documentary materials, which are after all another testimony of the reality we wish to understand. With regard to these, apart from the museum’s Historical Archive we must also take into account, as Sílvia Redondo, director of the Joaquim Folch i Torres Library, pointed out, the library’s collection of small catalogues. This material, which attests to a reality of female creation that, up to now, has been hidden among folders and filing cabinets, is currently being catalogued and studied.

Structural work is necessary, said Laia Manonelles, in which universities, libraries, museums and galleries are involved. Structural change is crucial; we should not have to depend on the thematic exhibitions about women artists or decisions subject to quotas. An across-the-board transformation would make thematic courses on women artists unnecessary because women would already be included in study plans. However, Manonelles added, apart from development of the content one must take care of the ways, that is, the consideration of policies of equality, of family reconciliation, and so on.

Among the key drivers for generating this transformation are encounters between people from different fields. Authors such as Maria Ruido or Núria Güell, said Laia, work collectively and place the focus of attention on the problems of women today; to some extent they make visible what has to be worked on, what has to be fought against. The personal is political and it affects all women. Therefore, the job of raising female artists’ profiles goes far beyond museum galleries.

Reflection as a point of departure

Mireia Rosich, as a member of the Art Museums Network of Catalonia, said that the objective of compiling a list of female artists was not focused only on putting on exhibitions and carrying out studies, but on reviewing and improving institutions’ acquisitions policies. Furthermore, on top of that there was the idea that it is necessary to work in a network, and that universities, artists and museums have to join forces and work together.

With this event the current situation of women artists in Catalan art museums was presented and a fluid dialogue on the subject was established. And it was made clear that there is still a lot of work to be done, and many issues associated with women artists must be studied, researched and published.

Related links

The imprint of women artists in post-war Barcelona

The imprint of women artists in post-war Barcelona. The creation process of a documentary exhibition

Biblioteca Joaquim Folch i Torres