Joan Yeguas

The reorganization of the Renaissance and Baroque art collection, which reopened in January 2018, made it possible to recover many works of art that had been kept in the storerooms for years. Many had previously been exhibited in the permanent rooms, whether temporarily during earlier reorganizations (like the one in 2004) or as short-term replacements of works loaned to exhibitions elsewhere; others, though, had never been exhibited, in some cases because they were in a poor condition, and they needed restoring.

A review of the works in the collection

Changing a collection around makes it necessary to make a detailed review of the group of works of art that have to be exhibited, those that are removed, and those that in future may substitute the ones that are now part of the discourse. All of them undergo a historiographical study; they all have to have a cartouche informing the public of the title and the painter, among other things. For this reason, we conservators gather and keep an eye on the reliable data that we have and make it known to everyone. At the same time, we also do research and propose changes.

New attributions

In an article appearing in the journal Acta / Artis. Estudis d’art modern, I wrote about the reorganization of 2018, and I also took the opportunity to review many of the works in the reserve collections, leaving to one side the best-known ones that often eclipse the rest. In this task I wished to make explicit the work done by M. Margarita Cuyàs, head of the National Museum’s Renaissance and Baroque Art Department from 1980 to 2013.

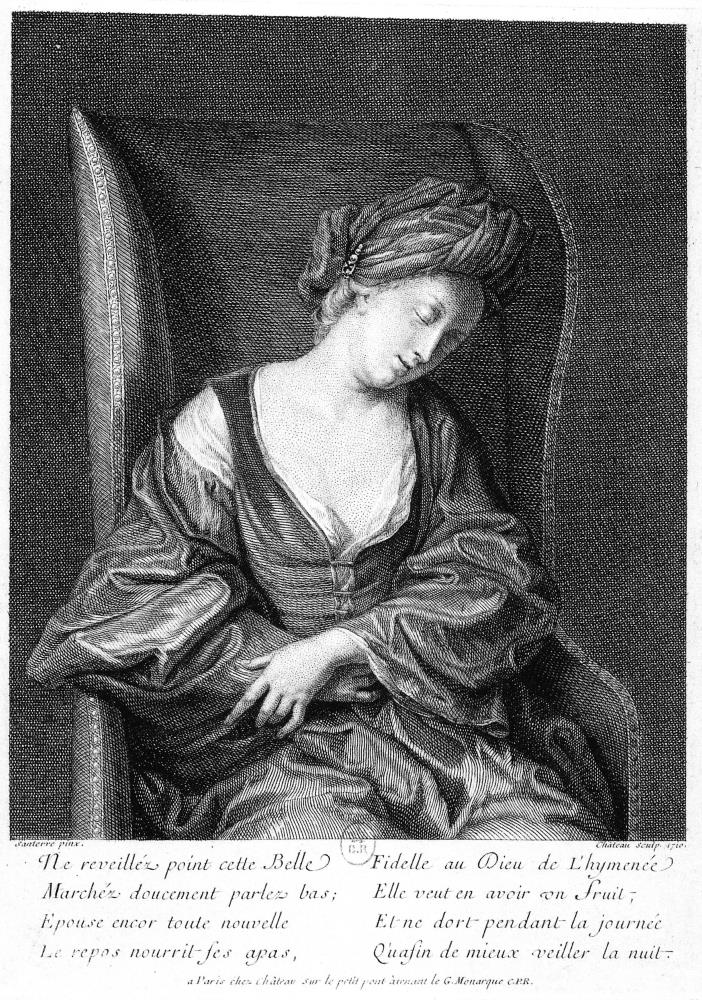

Cuyàs made attributions, which are still valid, and as they were still unpublished, I should like to make them known: The Holy Countenance by the circle of Albrecht Bouts, which follows the model of a true icon done by Jan van Eyck; two still-lifes with fruit and birds (Still Life with Pomegranates, Grapes, Birds and a Squirrel and Still Life with Pomegranates, Apples, Pears, Grapes, Figs and Birds) by Tommaso Realfonzo, “Masillo”; Portrait of a Young Man with a Wig by Nicolàs de Largillière; Saint Peter Martyr by Lluís Gaudin, identified as part of an altarpiece that the painter made for the convent of Santa Caterina in Barcelona in 1616, among others. A particularly interesting one is Young Woman Sleeping, attributed to Jean-Baptiste Santerre, depicting a young woman asleep who looks like Marie Adélaïde of Savoy (1685-1712), the mother of Louis XV of France, the model for which must be related to an engraving by Nicolas Château done in 1710, in which we see the same young woman in the same pose wearing the same dress and turban.

The latest artists added to the collection

In a final chapter I review attributions and suggest new ones. The Portrait of the Infanta Catherine Michelle, I attribute to Jan Kraeck (Haarlem, c. 1540 – Turin, 1607), also known by his Italianized name, Giovanni Caracca. Catherine Michelle of Spain was the daughter of King Philip II, married in 1585 to Charles Emmanuel I of Savoy, portrayed by Kraeck, a Dutch painter active at the court in Savoy.

Another interesting work is The Adoration of Christ with the Ayala Family attributed to the Flemish Juan de Roelas (c. 1670 – Olivares, 1625). Notice the presence of four members of a family as donors, identified with the count and countess of Ayala by a heraldic motif that appears among the jewels, almost certainly at the time he was granted the noble title (1602), something that coincides with the ages of all the sitters.

Children Begging, I ascribe to the anonymous naturalist painter called the Master of the Blue Jeans, active in northern Italy in the late 17th century. The depiction of poverty, with a curious and distant gaze, became fashionable in European painting in that period.

Master of the blue jeans, Children Begging, 1680-1700

The Presentation of Mary is a religious scene that takes place against a staged background. Because of the architectural perspective, Carlos Moreno Toledo (a student trainee at the museum) saw that the painter was using a work by the Dutchman Hans Vredeman de Vries done in 1557. Because of the majestic composition, the type of small-format figure and the rapid brushwork, the work has to be placed in the circle of Alberto Carlieri (Rome, 1672-1720).

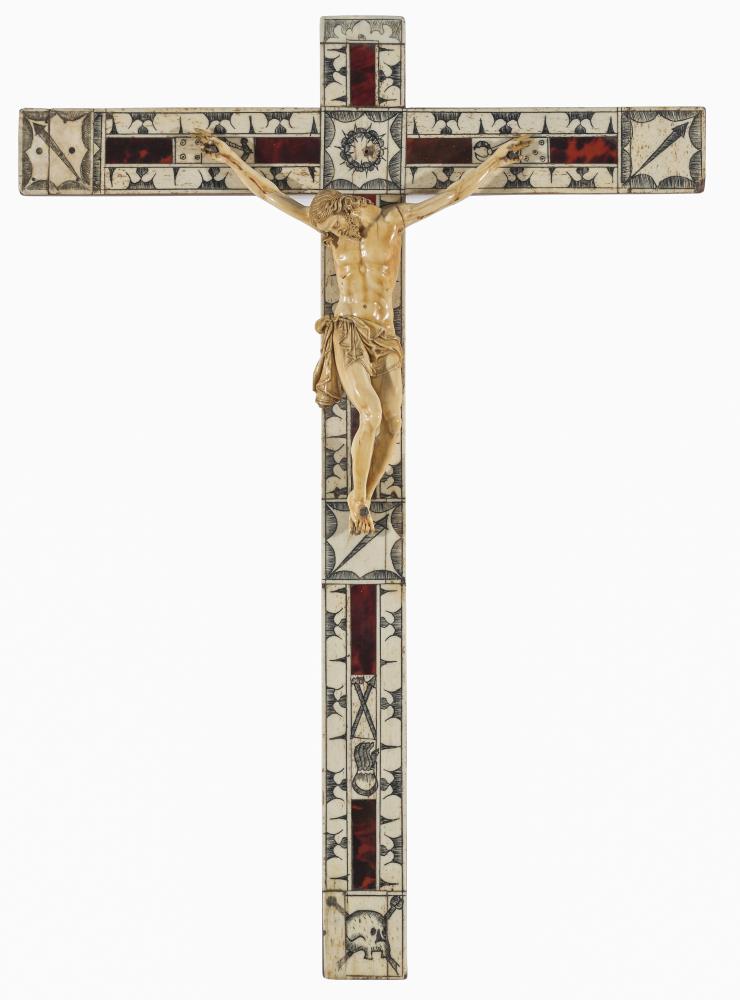

Circle of Francesco Terilli, Crucified Christ, 1600-1625

An ivory carving of Crucified Christ, with good anatomical work, which refers to works close to the circle of Francesco Terilli (born in Feltre, active between 1575 and 1635). Also of interest is the cross, most likely from Castile, with different instruments of the Passion: the crown of thorns, nails, dice, pincers, a hammer, a skull, a hand, and the Solomonic column of the Flagellation with a cockerel on top.

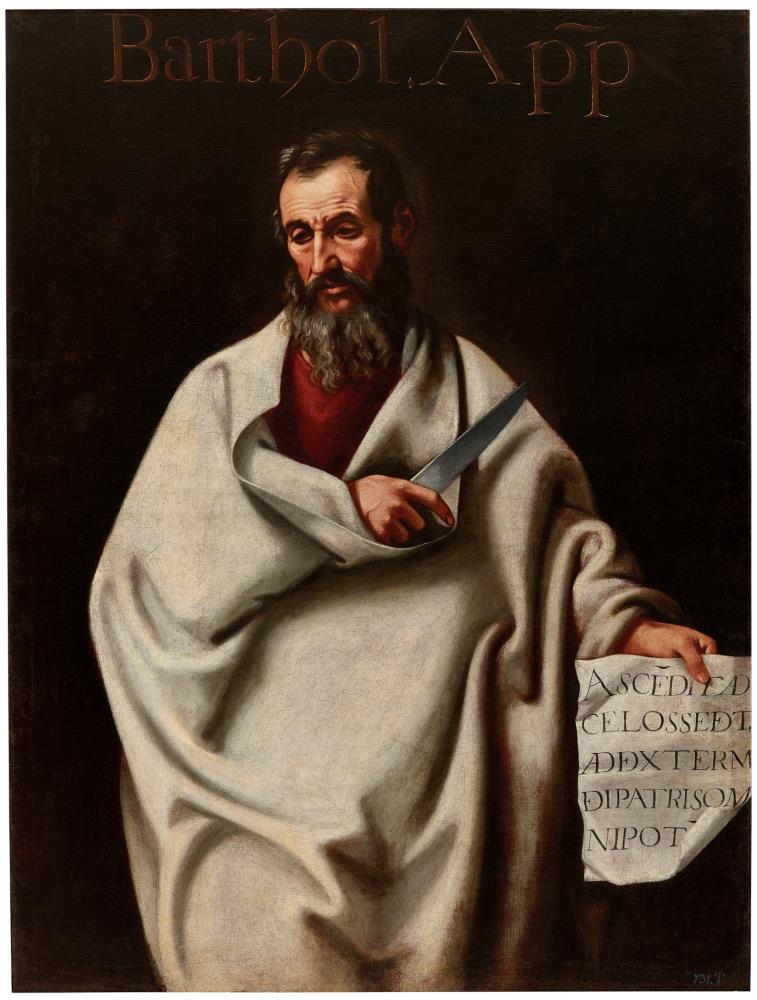

Finally, I have also analysed works that are currently in the storeroom, for instance The Israelites in the Desert, which I place in the late style of Antonio Maria Vassallo (Genoa, c. 1620 – died in Milan after 1664). Or a magnificent Saint Bruno, which is inspired by a sculpture of the same saint made by Manuel Pereira in 1652 for the front of the hostelry that the Carthusians of El Paular had in Madrid; the painting has to be assigned to the painter Cristóbal García Salmerón (Cuenca, c. 1603 – Madrid, c. 1666), because its style is identical – for the way he did the face and painted the robes – to the apostles done by him that are now in the Museo del Prado.

Related links:

New display of Renaissance and Baroque

Opening of the new Renaissance and Baroque galleries!

Four stories from the Renaissance and the Baroque

Art del Renaixement i Barroc