Júlia Lull Sanz

The social function of images

The art historian Georges Didi-Huberman suggests that images have the ability to “touch on something real”. This statement seeks, on the one hand, to underline the determining social function of images beyond their aesthetic value, and on the other, to stress the evocative and generative power that images have to open up new possibilities of relating to the world.

Until very recently, museums were seen as temples where all manner of experts, enthusiasts and intellectuals went to appreciate the work of the great geniuses of the past. In this regard, and as William Morris said at the end of the 19th century, museums are “the temples of the laity”, where the historical doctrine of the past is recited and accepted by the spectator with no opportunity to question it. These days, this concept has changed radically in that museums offer themselves to their visitors as open, inclusive and dynamic spaces with multiple possibilities for interpreting the past, with the ultimate goal of facilitating bridges and connections to the way we view today’s world. Thus, history is presented to us as a constructed narrative, open to being amended and revised by the museum, but also by its visitors.

Our world is full of deliberate fictional constructions that even today are accepted as established truths. The philosopher Michel Foucault devoted much of his time to studying the effects of power and the way truths are entrenched at different stages of history. In this respect, works of art become essential tools for studying and visualising how some of these fictions are produced as transmitters of the values, imaginary and constructed narratives of each past era.

The commitment of museums to avoid a patriarchal reading of the past

Museum institutions and their narratives have finally come to accept their responsibilities when it comes to reviewing the way in which the world has been explained, accepting that what we remember and keep as artistic objects is based on pre-established or partial selections. One of the greatest historical distortions is with regard to the role of women in generating culture.

The history of art is full of forgotten women. That is why one of the great paradoxes of art is the simple fact that, while there are an abundance of women used as models and objects of contemplation in the production of art, they are, conversely, absent as agents of cultural production. This reality, which over the ages has become normalised, perpetuated and accepted as “natural”, is nothing more than a fiction produced by a system of patriarchal social relationships based on the subjugation of women. Therefore, we cannot forget that our knowledge of the history will always be partial if we don’t accept that the views of the other 50% of society have been overlooked for centuries. We could even go as far as saying that half the world remains to be discovered.

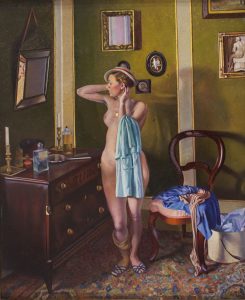

Not only that, beyond just the lack of works of art produced by women artists in our museums, we must add, as mentioned before, the excess of female representations based on the male imagination. The patriarchal and dominant capitalist imagination monopolised the production of images until very recently, creating and reinforcing a world view that excluded or undervalued anything other than the white heterosexual male.

In any case, if we view artistic objects as quintessential cultural artefacts, capable of providing us with a complex interaction with the past, we can use them to re-examine the processes behind the construction of the major fiction represented by the patriarchal system which, even today, seeks to govern our lives. As part of the permanent exhibition of the National Art Museum of Catalonia we find that, since 2014, seven women artists have been represented. This is a very positive fact taking into consideration that, before then, the number of women artists exhibited was zero. Even so, the proportion in relation to the total number of women artists remains totally unsatisfactory.

Art as a subversive tool

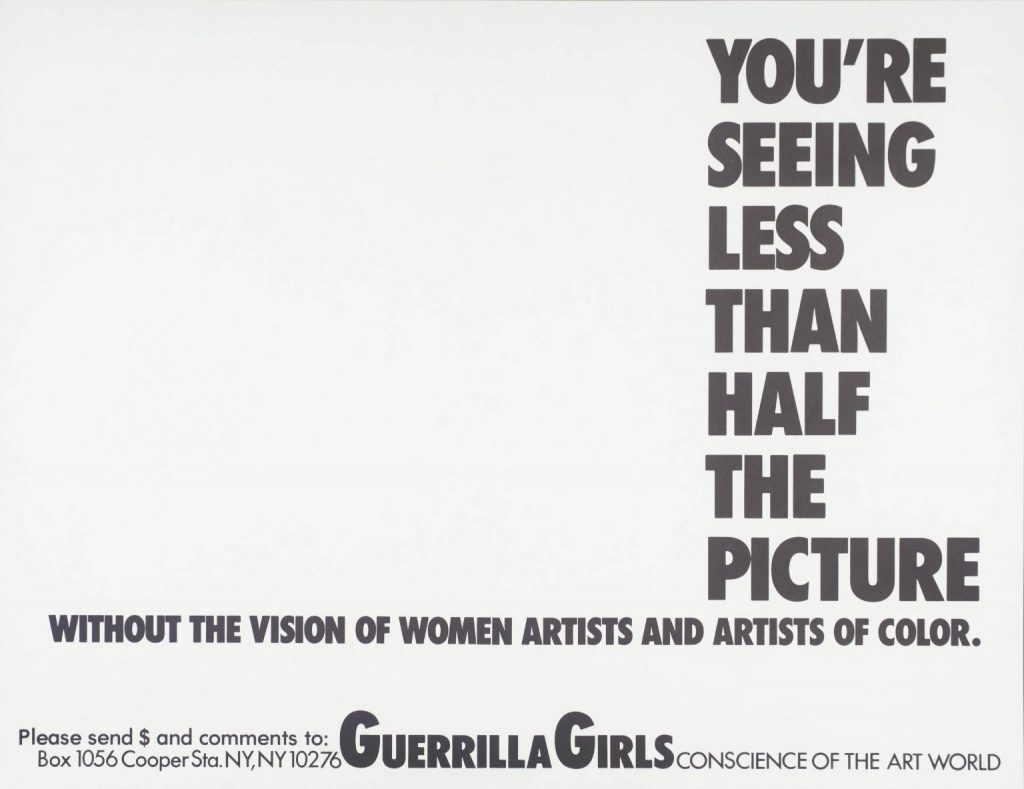

The work of these women artists opens up the focus and broadens our perspective of the past. According to the Guerrilla Girls (a group of feminist activist artists in New York created in 1985 to fight sexism and racism in artistic institutions): without the vision of women artists and artists of colour, you’re seeing less than half the picture.

When women speak through art, their work challenges the patriarchal system and can become a tool for subversion. The content of female art is, by its very nature, dissident and, as a consequence, original and innovative, as it puts forward hitherto unexplored viewpoints. Its positioning means that its artistic potential also implies political potential.

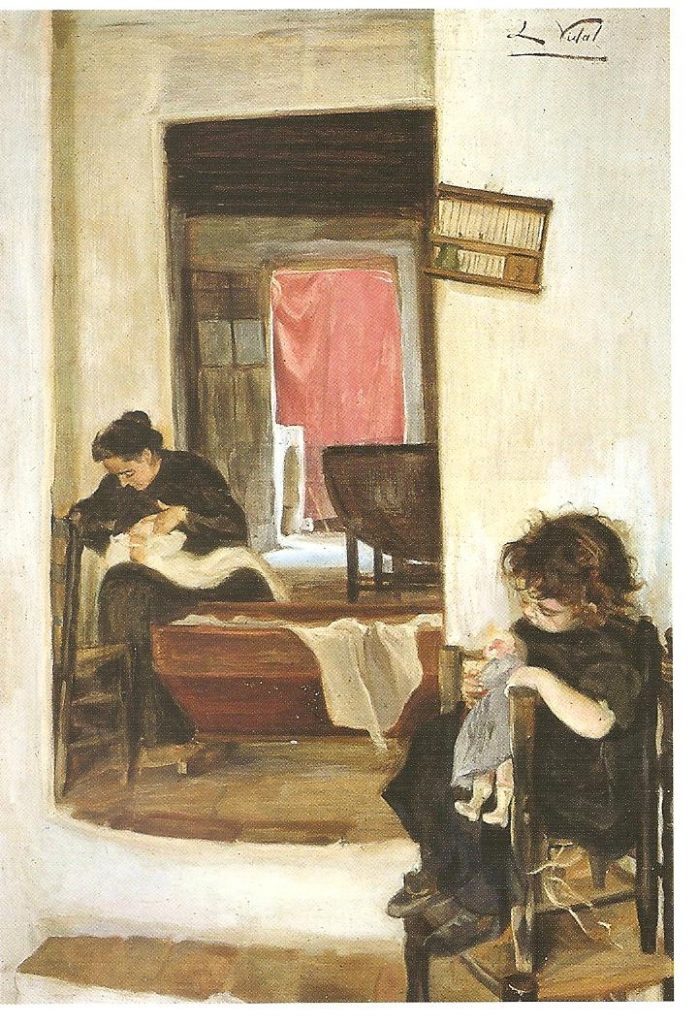

This was evident, for example in the Lluisa Vidal exhibition, a modernist painter, shown at the National Art Museum of Catalonia in 2016. This artist constructed a vision of feminine intimacy full of richness and complexity, while at the same time pointing critically to some of the reasons behind the perpetuation of the unequal social standing between men and women

Lluïsa Vidal, Self-portrait, c. 1899

In 1897, Lluïsa Vidal produced a rather special mother and child painting: neither of the subjects are looking towards us. In the foreground we see a little girl seated on a chair with a doll in her arms, imitating the pose of her mother who we see in the background nursing her baby. Obviously there is no hint of eroticism, provocation or sublimation in this scene. Vidal uses this work to expand the image of motherhood with the sordidly imitative “second mother and child” illustrated by the girl and the doll.

And yet the painting reveals to us a much more complete and complex story: if we look at it in detail, we see that between the mother and the child, high up on the wall, the artist has painted an empty cage, just at the apex of the triangle formed by those three points. We might ask ourselves if this cage has any particular meaning. It could be that the artist is talking about the destination established by the patriarchal system for all women from the time they are born. It is as if motherhood confirms the ability to produce life but also represents a prison for women.

Art as a symptom of the world that produced it

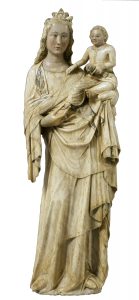

Art also offers us images that bring together and express many aspects of the society that creates it. In this respect, it was in the context of mediaeval Christianity that this stereotype of the woman-as-mother was most forcibly propagated, to such an extent that it marked the general social concept of what a woman should be. This iconographic model, borrowed from the primitive goddesses that were abundant during the Romanesque period and strongly reaffirmed in Gothic art, would perpetuate itself throughout the course of time with slight variations, on the basis of maternity being the main reason for women to exist. Women as machines to dispense affection and care, who are givers of life but yet express no sign of an autonomous or significant existence outside this reproductive relationship, confined to the home, with the private and domestic space kept separate from the public sphere to which they will never have access. This is a good example of how the powers that be at any given moment and their world view can affect the global tenets of society and even transcend them.

The male imaginary has treated women’s bodies as if they were no more than objects. This objectification of women’s bodies has, throughout the history of art, gone hand in hand with normalising and naturalising violence towards them and their bodies. From the scenes of the mythical rape and violation of women that form part of the cultural background of societies throughout history and which we can trace from Ancient Egyptian art through to the present day in its representation as advertising, we find ourselves up against the woman-object concept forming part of our visual culture, as is the violence suffered by their bodies.

The patience and resistance of artistic objects

If we think about it, artistic works expound and reveal truths to us in a patient and persistent way, waiting to be viewed in a critical and curious way by those who want to ask themselves why things are like they are. Through art we can discover, as Simone de Beavuoir would say, the processes by which women “are not born, but become”. When Didi-Huberman states that images “touch on something” he is referring precisely to their capacity to affect the way we look at them and to open up new possibilities, not just observing but understanding the world. As feminists know full well, art is one of the favourite means of deconstructing the patriarchal imaginary and a fertile field for experimentation and presenting alternatives that readjust and release our own imaginary.

Related links

Women in art. From the invented figure to their own bodies. Virtual tour

Women Artists at the Museu Nacional

Lluïsa Vidal, a woman artists in a men’s world

The evolution of women illustrated in art

Júlia Lull

Art historian, specialist in gender studies

Historiadora del l’art, especialista en estudis de gènere