Last year, the students in the second year of the Higher Diploma in Visual Arts and Design for Interior Design Project Management at the Escola Massana visited the museum. The results of this visit are six texts in which the students analyse and contextualize different items of furniture and the decorative arts in the Modern Art collection. The texts will be published grouped together in two posts.

Casa Mañach by Jujol: a work that is kept alive

Marta Peret Pujol

«The door handle is often the first physical contact that we establish with a building and, by extension, with its architect. Taking hold of it and pulling on the door, countering its weight with one’s own body, constitutes the most intimate encounter with it.» Juhani Pallasmaa

Wrought-iron door handle (59 x 44 x 11 cm) designed by Josep Maria Jujol i Gibert (and almost certainly made with the help of forgers Badia), in 1911 for Casa Mañach. The architect Ramon Tort i Estrada donated it to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in 2003. Next, a detail of the original handle and door. Photo taken from Sobre la tienda Manyac…

The door handle of the Casa Mañach locksmith’s shop sought the hands of passers-by in the Barcelona of 1911, inviting them to enter one of the most exotic shops in the then upmarket Carrer Ferran, planned by a no less surprising architect, Josep Maria Jujol i Gibert, from Tarragona. Although the shop is longer there, falling victim to the destruction of the Civil War, the wrought-iron door handle in the form of the Sacred Heart and sinuous shapes continues to invite the visitors to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya to delve into the architect’s creative world.

The aim of this text is not to offer a compendium of historical events or descriptive facts about the shop but, in reply to the door handle’s invitation, I propose to take a close look at Casa Mañach and, from its interior, I shall attempt to answer a question that I think is relevant for this or any work of art: which approach most faithfully restores the original spirit of the project?

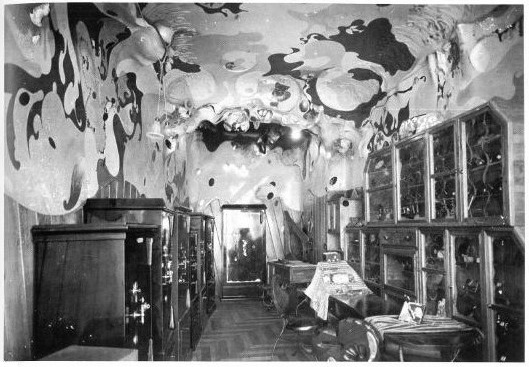

As Jujol confided to his student Alfonso Buñuel (an architect and the brother of the film maker), he wanted Casa Mañach to suggest «sauces mixed and rockets exploding». We would not be wrong if we were to infer that he wished to capture a fleeting moment, what is dynamic in the inherently static, to offer a spark of his vitality in a space where the commissioner of the work, Pere Mañach, had offered him complete creative freedom.

Thus, the first question leads to a second: can we talk about a place without mummifying it, without placing it inside the straitjacket of historiography? Can we talk about something without losing the state of surprise in the face of the unforeseen? In short: is it possible to offer a view of the Mañach shop that might allow it to be, forever, mixed sauces and exploding rockets?

Let us then grasp the handle and immerse ourselves (with this verb’s attributes of corporality and temporality) in a shop measuring only 35 square metres that has been described as a landscape of the deepest seas and a galactic vision, a fire and a monument to the Virgin Mary.

A work in constant progress

It seems obvious, in this landscape of stars, water and fire, that movement is its epicentral concept and this is linked, by definition, to time and space, an abstract dimension if not in relation to the body: temporality and corporality are the keys that enable us to capture the spirit of the Mañach shop. The architect Ignasi Solà-Morales argues that Jujol introduces time (and, I would add, the body of author and recipient) in two ways: he impresses it on the process and the diversification of the space.

Jujol’s work is always a work in progress, not because it lacks an end but because it shows «the sign of the work that has brought it to where it is at a particular moment». Jujol worked the materials personally, leaving them looking like something unmistakeably made by hand (for example, the sign on the front: worn, cracked, hand-painted, tortured). We could add that we had already seen signs of this when it was conceived through the drawing, when Jujol let himself be carried away and drew, lost in a daydream, in which thought, physical action and the material nature of the paper merged. Thus, the union of the mental and the corporal, in the drawing and in the execution, is expressed in personal shapes and lines that suggest a promise of undefined change. And this trait of the progressive nature of the work is precisely one of the most peculiar aspects of its reception: the promise of permanent mutation and regeneration

- Commercial plaque from Casa Mañach, 1911, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

- Elevation and section of the front of Casa Mañach, 1910. Arxiu Jujol.

- Knob, c. 1911, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

As a living entity, it also announces its finality and this latent fleetingness of the work is one of its most thrilling characteristics (that fleeting nature that we see in the lines of the body, in the modest materials that Jujol manipulated to paroxysm…). When all is said and done, we are looking at a typically Baroque confrontation (and Jujol showed a tremendously Baroque sensibility!) between eros and thanatos, the memento mori that reminds the body of its mortality.

The second strategy of the introduction of temporality is spatial diversification. With this I am referring to Jujol’s playful nature, designing doodles, incisions, anagrams and signs that he hid in every nook and cranny of the material, forming living maps that prolonged the discovery and suspended the surprise in time, as the gaze, the body, came into contact with the space. Although we can no longer walk through the Mañach locksmith’s shop, we can cast our eyes over the photographs and sketches of it that have survived, or the objects that were part of its fittings such as the door handle, the business plate and the knob conserved in the Museu Nacional (or others that have been exhibited there like the chair or the counter) and rediscover the surprise of the unexpected, with every symbol, every mark…

Chairs in the form of a bleeding heart (one of them is a replica) (85 x 52 x 69 cm) and counter, both in wrought iron and wood, designed for Casa Mañach in 1911 and belonging to a private collection. Bedmar Fotografia.

A wholly modern work

Now we are no longer in Casa Mañach; we have emerged once again into Carrer Ferran where a flood of passers-by admire the shop windows of the Masriera jewellers’ shop and drool in front of the Massana patisserie. And, from the street, we wonder about what we have just seen.

Photograph of the front at 57, Carrer Ferran, 1911, conserved in the Arxiu Històric del Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, and my own version with the colours suggested by Josep Llinàs in Sospecha de estiércol, Ediciones Asimétricas, 2015

The work of Jujol, as a work in progress, avoids fixed meanings. It is not that Jujol’s deliberate symbolism (the religious fervour exacerbated surely by the Tragic Week, or other more prosaic ones such as the depths of the sea) does not add value to its interpretation, but it is a discursive value that does not explain the artistic impact or the work’s validity today. Art makes it possible to feel the original astonishment of the unexpected and here the concept “original” is crucial, as it implies that it moves us when it appeals to some pre-existing thing, we might say, a corporal memory that shuns language.

We could therefore argue that Casa Mañach is a wholly modern work by including temporality and corporality in the aesthetic experience, but above all because, in doing so, it embraces the conflict between its fundamental terms: between architecture and movement, architecture and finality (just think of the classical firmitas and soliditas) and between work and meaning.

To learn more about Casa Mañach

The Cendoya Oratory by Joan Busquets and the hidden language of flowers

Ingrid Barrera Panós

The first time I visited the museum I immediately went to visit the Modernista interiors. Among many pieces I found one that I was not expecting to see and which awakened my curiosity, the oratory by Joan Busquets and Josep Pey, but standing behind the railing it is difficult to appreciate some of the secrets it conceals.

Built in 1905, it was originally just another part of the house that the married couple Antonio Domingo Martínez and Josefa Torres Gener had at 53, Passeig de Gràcia. This small room was quite common in the early twentieth century among the families of the Catalan bourgeoisie who could afford it. Replacing the chapel, it was a reserved space set aside for religious worship in the family home that met the need to be close to God.

It may seem strange to see Modernisme at the service of the faith in a period when moral values and religion are being questioned, as it seems that the latter disappeared during that period, but nothing could be further from the truth. Through symbolism, even the flowers refer to it, as in the case of the ceiling of this space.

Flowers and nature are one of the principal characteristics of Modernisme and they are the inspiration for the art of this period. The hidden language of flowers comes from the Middle East. Through the Persian practice of selam Persian women managed to code messages, thus evading their guardians. This floral language became particularly important in France, the model that Barcelona adapted. We thus know that the gladioli on the ceiling are a reference to inner strength and moral integrity, while the sunflowers, one of the most popular flowers in Modernisme, are associated with development and personal growth, in connection with the divine. Just like a flower, an individual is expected to devote their life to a constant search for the light.

We see these sunflowers on the railing across the entrance to the space. There are roses too, which appear closed at the entrance, and open at the back, when they meet the hanging lamp, representing the lifecycle that culminates when it finds the light. This is also a symbol of Catalan nationalism, a recurring image that we find in Modernista stained-glass panels and facades in Catalonia.

Ceiling light from the Cendoya Oratory, 1905 i roof del Secession Hall a Viena © WienTourismus / Claudio Alessandri

The image of this lamp reminds us of the roof of the Secession Building, a symbol of Viennese Secessionism, something that highlights the connection between the different manifestations included in Art Nouveau in different parts of Europe.

Viennese Secession served as inspiration for Busquets i Jané, a cabinetmaker and decorator, who took over from his father in charge of the family business that his uncles had founded, and he took it upon himself to design the whole oratory, except for the drawing of the angels and the paintings of the willows, work that he gave to Josep Pey.

With the aim of producing Modernista furniture intended to integrate art and decoration, it is surprising to see the chair and the prie-dieu, designed for this space, with a rather more medieval look than the space itself.

Prie-dieu and chair from Cendoya Oratory, 1905

Although Joan Busquets i Jané is considered an important figure in Catalan Modernisme, the style of his furniture corresponds to the fashion of the time, eclectic and historicist.

In charge of Casa Busquets, he received orders for customers in the Catalan bourgeoisie, intellectuals and politicians, from both Spain and Latin America. The firm, specializing initially in the production of tapestries, became a shop and workshop until 1949, one of the forerunners of Art Deco.

It may seem that spaces such as the oratory and all its symbolism belong to another century, but as our homes have grown smaller, a small part has been kept, such as an altar or even a religious statue. This obvious distance was what captivated me from the first moment, but after delving into its mysteries this distance seems to have disappeared.

What piece in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya has left you wanting more?

Cloisonné glass, a short-lived delicate technique

Ione Beobide Murua

From afar, one of those fantastic stained-glass panels that Catalan Modernisme left us: floral patterns, symmetries, precise drawing, subtle shades, wavy lines…

From up close, a surprise: What are all these tiny little glass balls and beads in different colours combined as if they were a watercolour?

Frederic Vidal, Four-leafed glass door, Wood and cloisonné glass, c. Two details of the techinique of cloisonné glass. (1) Photograph taken from Viquipèdia (2) Photograph taken by Sol Urbano, april 2019.

Cloisonné glass

This is a technique for decorative glasswork that was developed in a brief period of time during Modernisme, from 1897 to 1904. The name comes from the French term cloisonné (partitioned), which also defines an old oriental technique of artistic metalwork with enamels, used to make jewellery, trays and other decorative objects.

Cloisonné glass was applied chiefly in stained-glass panels, windows, screens and lampshades. On these supports where light – artificial or natural – plays a part, the transparency of the glass beads and spheres, coloured in subtle shades, added to the shine of the gilt metal used to make the partitions (cloisons), produces delicate, very bright finishes.

According to Amedée Naverein, the French artist who invented this technique in 1894:

“… To put my invention into practice, first you draw the design that you wish to reproduce on a piece of paper. Over this paper you place a flat panel of glass through which the design of the outlines of the drawing can be seen. Then strips of wire of a suitable metal, such as polished brass, are bent to follow the outlines of the design drawn on the paper. These wire strips are glued to the glass panel using an adhesive material, such as gum arabic. When the adhesive material has hardened, the spaces are filled with glass beads or similar materials of the required thickness and the right colours to form the ornamental design. These glass particles or granulates or similar materials are placed in a thin layer, and must be glued or joined using an adhesive material, preferably fish glue mixed with a small amount of potassium dichromate to prevent the glue from absorbing moisture from the atmosphere, and to make it easier to dry. This adhesive material is applied preferably with sufficient heat. Only a small amount of dichromate is used, to prevent the glue from being coloured. The glue is spread over the glass beads or granulate, or similar material, in just the right amount for the particles to stick to one another and to the glass panel. The panel thus prepared dries at a suitable temperature of about 30° C. A second glass panel can be placed on top of the wire strips, and the edges of the two glass panels can be sealed together using putty to avoid air getting in …”

I have taken, and freely and approximately translated, this description of the cloisonné glass technique from the English text of the patent assigned by Amedée Naverein to two industrialists, Theophil Pfister and Emil Barthels, in 1897. That year, Pfister and Barthels founded the firm The Cloisonné Glass Co. in London, making stained-glass panels for decorating windows, screens, ceilings, lampshades, tables and other ornamental objects. The company was short-lived, as it was wound up in 1900.

The Catalan connection

Image taken from the book Vidrieras de un gran jardín de vidrio by Manuel García-Martín 1981

The cloisonné glass technique reached Catalonia thanks to the Barcelona industrialist Francesc Vidal Jevellí (1848-1914). A great lover of the arts and a patron of musicians such as Pau Casals and Enrique Granados, Vidal had studied decorative arts in Paris. After finishing university, he founded a company in Barcelona working in decoration, in whose workshops cabinet making, iron casting, stained glass, upholstery and interior decoration in general was done. It was very well known in the period and received orders to decorate the houses of the most important families of the Barcelona bourgeoisie.

In 1898 Francesc Vidal sent his son Frederic Vidal Puig (1882-1950), aged 17, to learn the cloisonné glass technique in the workshops of The Cloisonné Glass Co.,in London. Frederic, who had been good at drawing from a very early age, learned the technique in just one year in England. Upon his return to Barcelona, he incorporated his knowledge into his father’s company and started making stained-glass panels with the cloisonné glass technique.

Frederic Vidal attempted to train the workers in the company’s stained-glass workshop, but he did not have much success; after six months, the workers refused to continue learning the cloisonné glass technique since they found it difficult. Indeed, seeing the description of the process and the delicate results, it is obvious that to master the technique you do not just need to be an excellent draughtsman, but also to have great manual skill to put the wire strips and the small spheres and beads of glass in place. Moreover, you need to have a mastery of painting techniques to achieve the motifs’ subtle shades of colour.

Photograph taken by Sol Urbano, april 2019

Frederic Vidal continued making cloisonné glass panels until 1904, chiefly to decorate the house of Eusebio Bertrand i Serra, at 37, Passeig de la Bonanova in Barcelona. That year, he moved to Argentina where he lived for nine years, unconnected with any artistic activity, apparently. When he returned to Barcelona in 1913 he resumed working with his father, and after the latter’s death the following year, he took over running the company. But he never did any more work using the cloisonné glass technique.

And the technique was forgotten…

Rediscovery of the cloisonné glass technique

In 1981, due to the imminent demolition of Bertrand’s house, his heirs donated the collection of stained-glass panels in the house to Barcelona City Council. The majority of these pieces are now in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

This rediscovery led to a profound study of the unknown cloisonné glass technique by the company J.M Bonet Vitrall, S.L. and the professor and historian Manuel García-Martín, who wrote two books on the subject: Vidrieras de un gran jardín de vidrio and Las vidrieras cloisonné de Barcelona. Also, the restoration of a piece of cloisonné glass began in the workshops of the Casa Elizalde, although the results were not very satisfactory.

Regrettably, there was no information about the materials and the method of making cloisonné glass until more than 20 years later, when the professor at the University of Applied Sciences in Erfurt (Germany), Sebastian Strobl, published the patent document that I mentioned at the beginning of this article in the course of a congress held in Namur (Belgium) in 2007.

With these new discoveries, Jordi Bonet, the third generation of the company J.M. Bonet Vitrall, S.L., resumed the restoration of cloisonné glass panelsand made an extensive study that he published in January 2013, in collaboration with Trinitat Pradell, a professor at the UPC, entitled: Cloisonné stained glass: material analysis and conservation issues.

Currently, Julia Lahiguera, a designer, ceramicist and artist of other disciplines such as mosaic and trencadís, is studying and working with the cloisonné glass technique in her shop-workshop Brots Creatius, in the Gràcia neighbourhood of Barcelona.

Is this a rebirth of this delicate artistic technique? Only time will tell.