Francesc Quílez

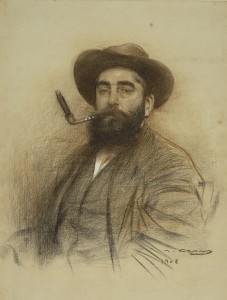

Ramon Casas is a paradigmatic example of the modern artist in any literal sense of the term. Critics and historians have pointed him out as a great painter and the creator of some of the most emblematic and iconic works in the history of Catalan art. With his nonconformist attitude, Ramon Casas managed to rouse a feeling of empathy and complicity in a public who looked on his works as a mirror reflecting a shared system of values. The public’s familiarity with Casas’s work, often summed up in an ironic smile, was also influenced by the actions of an artist who was seen as a mischievous child, a petit bourgeois playing a game of provocation, luckily an inoffensive one whose actions never altered the social order.

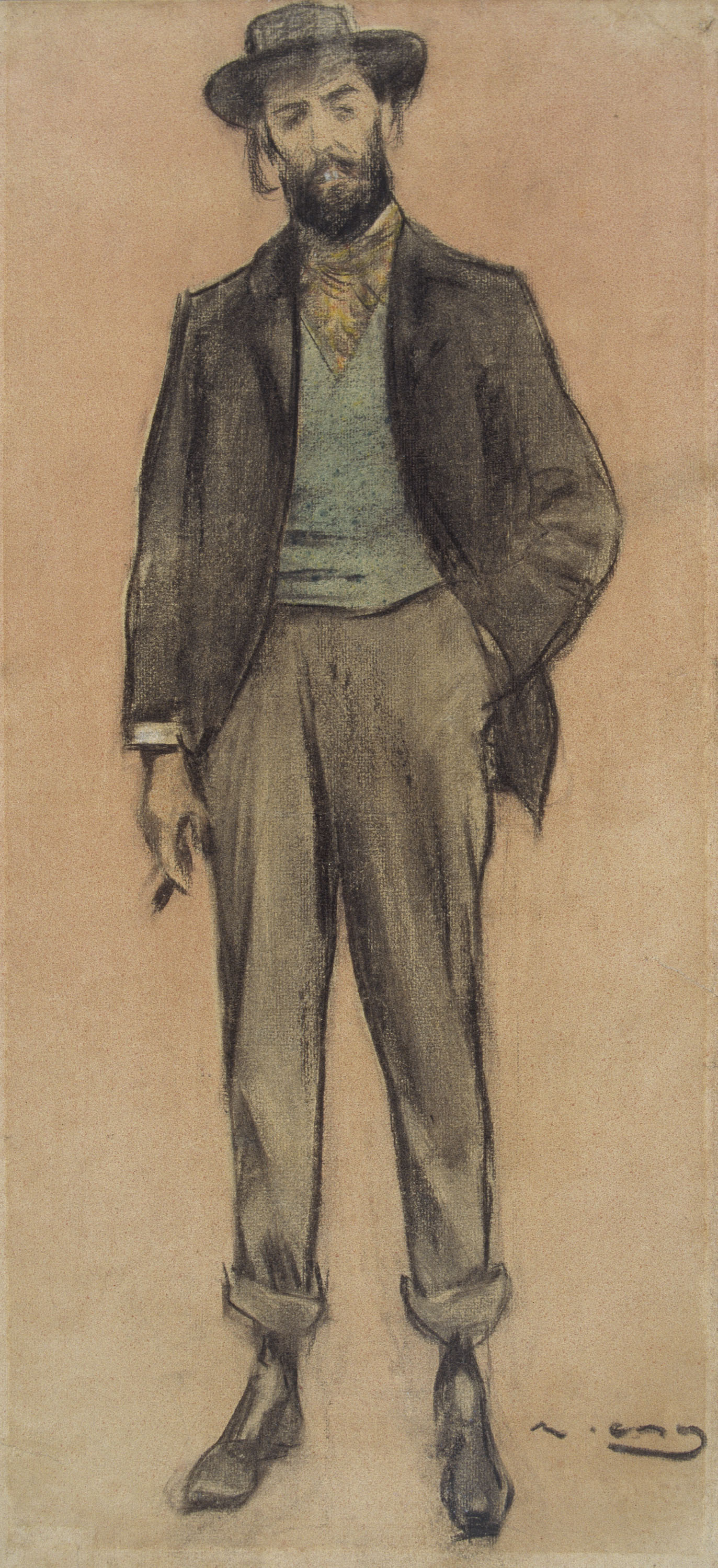

Ramon Casas. Self-portrait. 1908

Born into a well-off family, the painter decided to take a different path to that of his social background and adopted a bohemian way of life. Endowed with innate talent and skills, Ramon Casas played a part at the forefront of the Catalan painting of the late 19th century and helped to steer the short-sighted localist approach that dominated the work of most Catalan painters of the time towards a new, cosmopolitan horizon with more ambitious expectations.

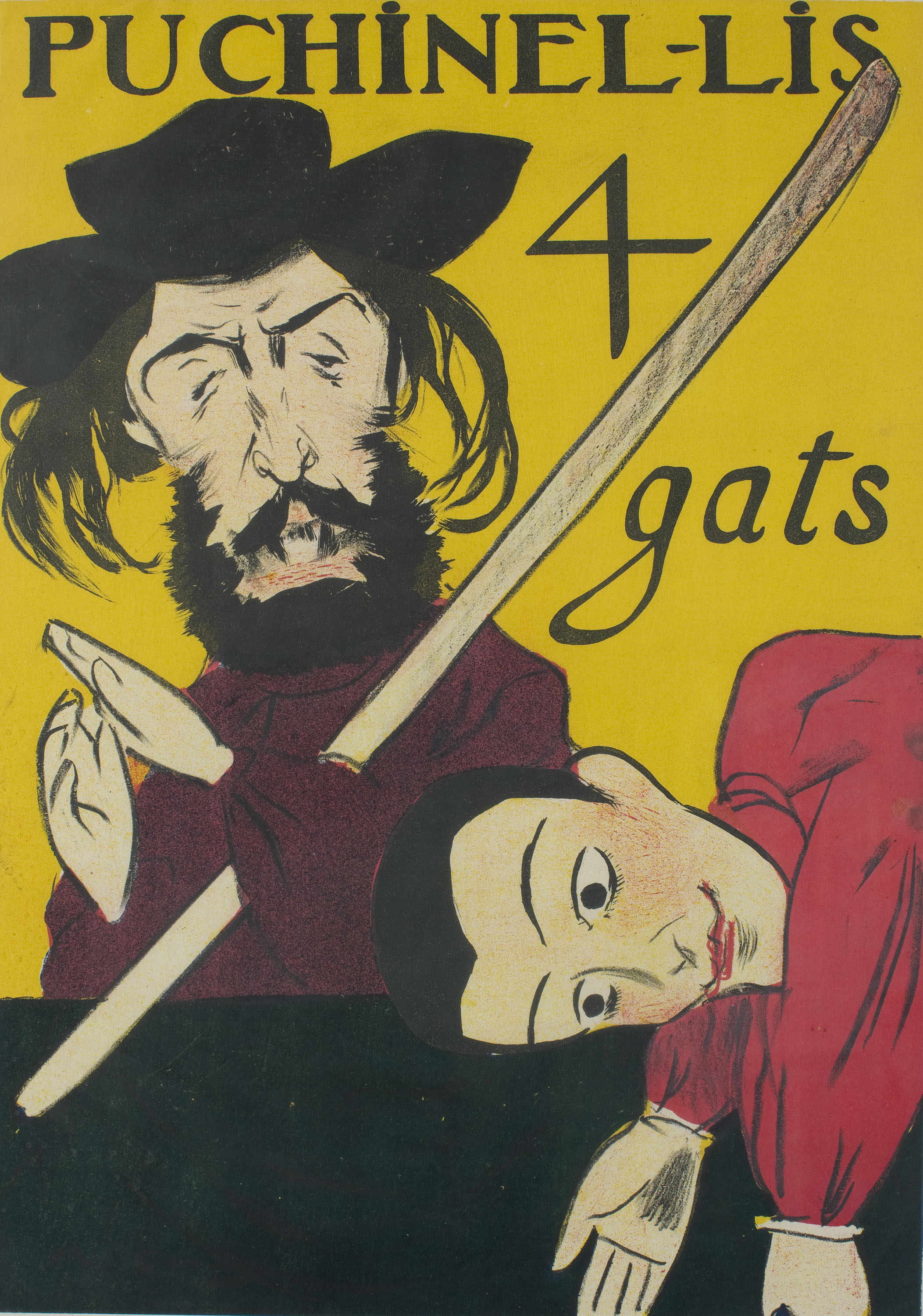

In Paris, in search of a fertile contact with Europe’s most avant-garde and dynamic pictorial centre, he must have projected his personal wish for renewal. His innate curiosity was stimulated and revealed his need to reinvent himself and adopt a provocative attitude of épater le bourgeois. This did materialise in bohemian activities fed by an open, broad-minded culture that was highly receptive to the introduction of new ways of understanding art. One of Casas’s most unusual and original contributions to the birth of the first episode of organised modernity to emerge in Barcelona, following the opening of the beer hall Els Quatre Gats on 14 June 1897, was undoubtedly the understanding, which became a practice that the traditional separation between high and low culture had to be overcome.

Els Quatre Gats, a scenario for presenting new artists

The influence of Paris was a decisive factor in the formation of the core of Els Quatre Gats, the founding episode of a bohemia with a militant leaning. After all, this intergenerational stronghold owed a debt to the atmosphere the generation born in the 1860s had found in the most cosmopolitan and avant-garde city in Europe at the time.

The lively atmosphere that must have prevailed at Els Quatre Gats from the moment of its inauguration made it the ideal setting for an urge for freedom that moral conventions prevented from materialising. Irony, a sense of humour or a comic view of the reality around them was precisely what came to define and fully characterise the group at Els Quatre Gats.

This atmosphere created at Els Quatre Gats favoured the apparition of unorthodox practices that illustrated cultural traditions of a popular nature, like Chinese shadows or puppets, which were rooted in the popular imaginary.

The Chinese shadow puppets at Els Quatre Gats

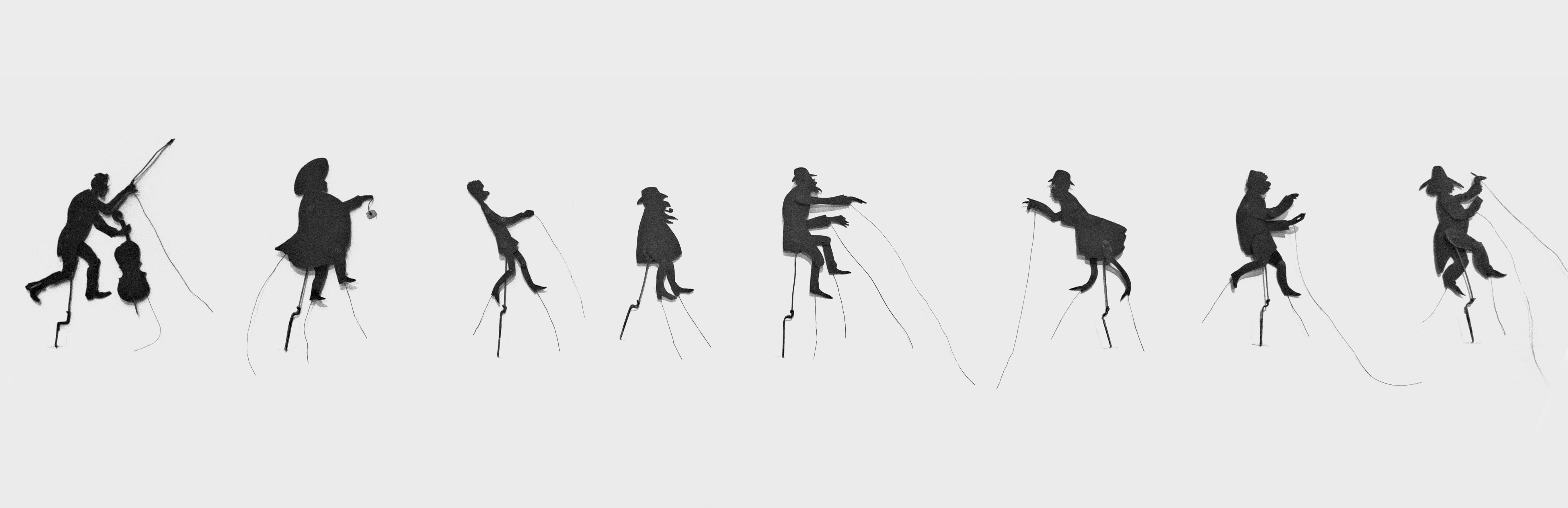

The unique set of the shadow puppets kept at the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya has recently enriched our Casas’ exceptional collection. It is a group of 11 shadow puppets. They are a testimony to a very popular practice which in this particular case combines the talent of their designer, Ramon Casas, and the technical ingenuity of the creator of these articulated beings, the doctor Josep Meifrén, with whom Casas always kept up strong bonds of friendship.

Ramon Casas and Josep Meifrèn. Chinese shadow puppets for Els Quatre Gats. Deposit of Pere Jiménez-Meifrén Caralps

The set constitutes a model of hybridisation, of synthesis, which gathers the forms of popular amusement that were well established in 19th-century Barcelona. This is borne out by the existence of prints depicting this type of traditional performance and also by the Modernista revival of this type of artistic practice. This reinvention brought it added artistic value, combining Ramon Casas’s creativity and the influence of new languages, new art movements like poster art or Japanese aesthetics, which also had a visual influence on developments in Chinese shadow theatre and on the figures used in it. In this respect, the design of the figures, with their sketchy features, exemplifies the process by which these models were assimilated.

Casas’s personal style is especially felt in the caricaturish air with which he draws the outline, the silhouette of each of the puppets, and in some cases emphasises certain facial features that help identify the character.

Presumably, the figures must have been easily identifiable for spectators and must have had some bearing on the subject of the event. Formally, the designer emphasised the most characteristic features of each model and used an exaggerated, often comical, register. In this respect, we have been able to identify some of the protagonists from their exaggerated defects and, in other cases, propose a hypothesis which, with the natural methodological caution, seems plausible to us, as we can compare the puppets with portraits of the time, either in drawings, some by Casas himself, or in photographs. In this way, in some of the pictures we have managed to identify what could be portraits of Pompeu Gener, Àngel Guimerà, Pere Romeu, Miquel Utrillo or a self-portrait of Ramon Casas.

The Chinese shadows were very popular in Barcelona, as we see from the large amount of graphic material documenting the dissemination of this repertory by Barcelona publishers. In general terms, these are single sheets on which are printed the silhouettes of figures making up a wide range of characters, creating a type of traditional storytelling.

Related links

Temporary exhibit of Chinese shadow puppets

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats