Eduard Vallès and Francesc Quílez

The following sections are devoted to reproduce a selection of works by Nonell. The works are divided into several sections that correspond to his main artistic interests and the themes he explored. Each of these centres of interest is illustrated by some of Nonell’s most outstanding pieces, linked to their artistic context, which is why the presentation is thematic rather than chronological, as we feel that presenting the works by subject demonstrates these links much more clearly. This approach also places the works within the context of international artistic movements and establishes a dialogue with the modern tradition.

“Local” naturalism

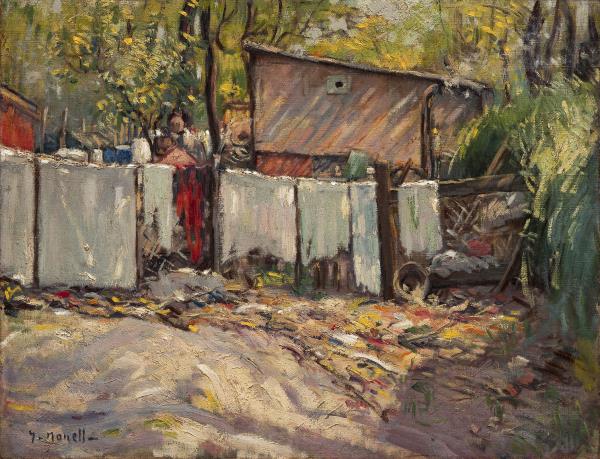

Nonell’s formation as an artist, like that of many young people of his generation, owes a large debt to nineteenth-century French painting as well as, particularly, the naturalist works of practitioners like Santiago Rusiñol. Naturalism was a reaction against idealism that, in a way, formed a perfect environment for Nonell’s evolution as he gradually distanced himself from the aestheticist stances of the first modernist generation. At that time, however, Nonell was still in the early days of his career, seeking to forge a language of his own, one that would bloom years later when he began to focus on the margins of society. His early works were set in his immediate environment, such as the family home, and often feature terrace roofs or humble courtyards.

Nonell never seeks to sublimate these modest, often secluded spaces, and the gaze he casts on these surroundings is imbued with a certain melancholy. In fact, this interest in quiet, humble spaces was in line with the semi-Impressionist landscapes imported from Paris by such artists as Rusiñol and Casas and which Nonell – like so many artists in his circle – undoubtedly admired as he started out on his career.

These compositions feature ochre and grey tones, and the human figure is not always present in them, or is merely a complementary element to the space itself, which has its own entity. Other notable works include his interiors depicting workers in shops or factories, often partially hidden or with their backs turned, hinting at a certain idea of the alienation caused by work, a technique also seen in many other painters of the time. In a way, factory workers were the interior human landscape that complemented the exterior landscapes of the suburban areas that he was painting at the same time, and which reflect the growth of the city in the late-nineteenth century.

Nonell became the chronicler of that workers’ microcosm, which suggested these visions so close to his personal reality, but so unlikely to produce commercially successful art. In the period in which Nonell produced most of these works he had not yet travelled to France, but there is no doubt that he had already assimilated lessons from European painting, if not directly, then by studying paintings by artists who had already visited Paris.

Cartography of a wild landscape

In the summer of 1896, Nonell, accompanied by his fellow artists Ricard Canals and Juli Vallmitjana, embarked on an adventure whose outcome was uncertain and which took them into the heart of the Boí Valley. After a long and arduous journey, the three friends took accommodation at the spa hotel in Caldes and began a sojourn that would have immediate repercussions for Catalan art.

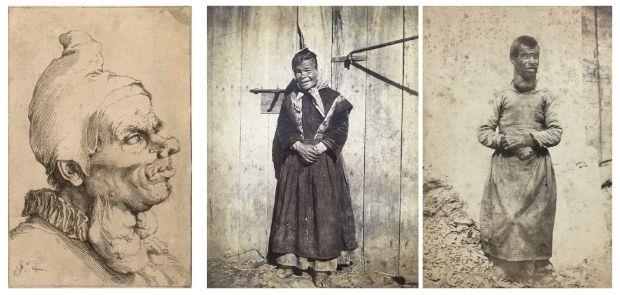

In this remote area in the Catalan Pyrenees, Nonell came into contact with the inhabitants of the surrounding villages, some of whom suffered from congenital disorders and illnesses that prevented them from fully developing their upper and lower extremities, as well as causing disproportionate growth of the thyroid gland. These two conditions, typical of places where endogamy still persisted, led to the appearance of people suffering from cretinism and gout, respectively. Far from being repelled by these images, Nonell entered into one of the most surprising and fascinating relationships in his life as an artist, turning these stigmatised characters into a source of inspiration that marked one of the most fertile periods in his creative career.

A few days after their arrival, the friends received a visit from Ramon Pichot and the critic Josep Maria Jordà, who had been invited to accompany them for a month. In an article published later, Jordan humorously narrated what he described as an “outlandish” journey. In his short account, Jordà not only recounted some of the misfortunes that befell them, but also described Nonell’s great devotion to his art, which gave fruit in the form of a large number of drawings, conserved in several portfolios.

Following his Pyrenean journey and over a period of around six years, he painted scenes featuring characters that he always respected and treated with dignity. Nonell was able to separate these characters from their condition as strange, anomalous creatures, and thereby contributed to dispelling the sinister prejudices to which they were subjected.

Although, inevitably, there was a bias towards the picturesque in his production on the theme, this visit to the Boí Valley unintentionally became an important landmark in the artist’s career and, by extension, deserves to be considered, without exaggeration, as one of the most outstanding episodes in the history of Catalan art: a sort of founding manifesto of artistic modernity.

The confines of the metropolis

Apart from works inspired by his short stay in the Boí Valley, Nonell took two major cities as the settings for his work: Barcelona and, for a relatively short time, Paris. Barcelona was in those days a great capital immersed in rapid industrial growth and with all the contradictions inherent to those huge metropolises, generating both wealth and inequalities. In fact, some of Nonell’s landscapes include the appearance of factories and chimneys as symbols of the new age.

Despite the predominance of the portrait in his career, Nonell also produced many landscapes during his early years, and these works featured largely in some of his first exhibitions and submissions to official shows. He shared this interest in landscape with many contemporary artists, some of them fellow graduates from Barcelona School of Fine Arts who, like him, later exchanged the classroom for plein air painting.

These young people took inspiration from French Impressionist works that they had seen, in part, in the Montmartre landscapes that Rusiñol and Casas had imported years ago and which, at local level, had a precedent in the Olot School. The group of artists became known as La Colla del Safrà (the Saffron Group), or La Colla de Sant Martí, names that allude respectively to their colour palette and to the areas in the outskirts of the city where they used to go out to paint. Despite the heterogenous nature of the group’s members, they all shared certain aspects in their practice. These included an interest in the city suburbs and the urge to experiment with atmospheric effects on the landscape in their paintings. We can identify two types of landscape particularly. Firstly, works composed of yellows, ochres and greens, often with added effect caused by hazy sunlight. Secondly, recreation of the effect of the noonday sun on landscapes or buildings, painted in very bright yellows.

Secondly, recreation of the effect of the noonday sun on landscapes or buildings, painted in very bright yellows. However, Nonell would devote little of his artistic career to landscape painting.

Another prominent member of the group, Joaquim Mir, continued to work on the theme for several more years, creating some of the most iconic works in the field of representing light, an aspect in which he would become a master. For Mir, the Saffron Group – which Nonell and other artists considered an epilogue – represented the prologue to a career that would see him established as one of the great European landscape painters of his time.

From now on, the landscape would become merely a footnote in Nonell’s work, with the exception of his portrayals of shanty housing. He had started painting these slum areas in the late-nineteenth century, but would continue to return to the theme regularly over the years. Seen through Nonell’s gaze, those miserable shanties, some of them perhaps home to his marginalised models, are richly imbued with sensuality and lyricism.

Miserabilism

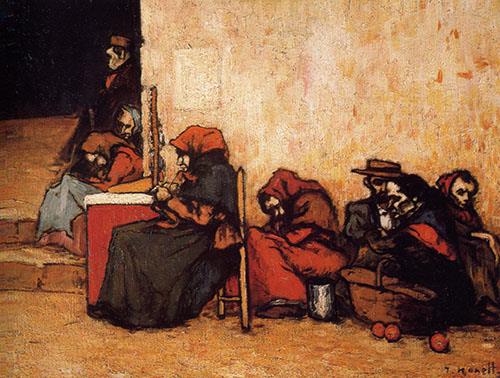

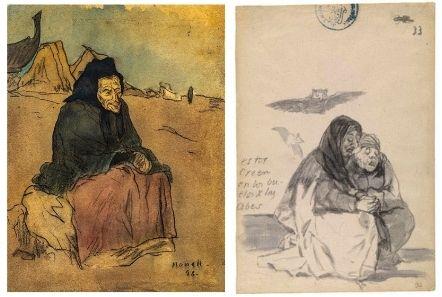

Social themes are among the main elements in Nonell’s work. The poor, the destitute, the needy and the excluded form part of the poetic of miserabilism, which found one of its leading representatives in the Catalan painter. However, despite focusing on a context full of adversity and the logical contradictions that revealed the miseries of the capitalist system, the artist never sought to express the aspirations of social emancipation that drove proletarian organisations.

Nonell’s is a brutal, despairing vision of beings who are not masters of their own destiny but are immersed in a situation of permanent rootlessness and abandonment, lacking the strength to rise up and rebel against the social fate to which they appear doomed. At around the turn of the twentieth century, large sectors of society lived in subhuman conditions, in unhealthy shanty towns, surviving by begging or on charity.

These were people who could not even dream of getting a job, excluded as they were from access to employment. Through his work, then, Nonell rescues this large group of marginalised people from invisibility, and he does so by placing his art at the service of a hopeless cause. His models have no possibility of redemption, and are excluded from a system that rejects them, so the artist activates the mechanism of poetic justice and confers on them a leading role. However, this elevation would elicit a response of disgust and incomprehension from the bourgeois elites.

These works have evident similarities with Nonell’s portraits of gypsy women, as this is not such a different theme, and the two subjects share elements in common. In fact, all these pieces can be interpreted as fully-fledged manifestations of what has been described and become known as the genre of miserabilism. Poverty, abjection, precarious living conditions and so on inspire and impregnate all Nonell’s work. Accordingly, this spirit of resignation, of heavy sorrow, of unwillingness to fight or revolt against poverty and unjust circumstances forms part of his imagery and is an element found throughout the geography of his artistic career.

In fact, the protagonists of his stories are the most disadvantaged, the most marginalised, the lumpen-proletariat that have lost all trace of class consciousness, people who survive in misery, dwelling on the very periphery of the system.

This text is an excerpt from the book recently published by the Museu Nacional about the artist Isidre Nonell Nonell. Visions from the margins.

Related links

Nonell. Visions from the margins

Nonell in context. Beauty from the margins

Francesc Quílez

and

Art modern i contemporani