Àlex Mitrani

Changing everything

“A world is falling apart”, said a highlighted phrase in an article on 18th December 1968 in Tele-Express, entitled “Hippies y beatniks en la Plaza Real”, accompanied by a second article, “El ‘Underground’, cultura de subversión”. Three English terms were used to label a sociological phenomenon: the appearance of groups of young people who behaved outlandishly, and who, to the conservative way of thinking of the time, seemed to be seriously subverting the natural or traditional order of things. Despite the condescension, some feared that the forms of behaviour and the ideas of these young people represented a transgression that endangered civilization, signalling the end of the world as they knew it. And maybe they were right …

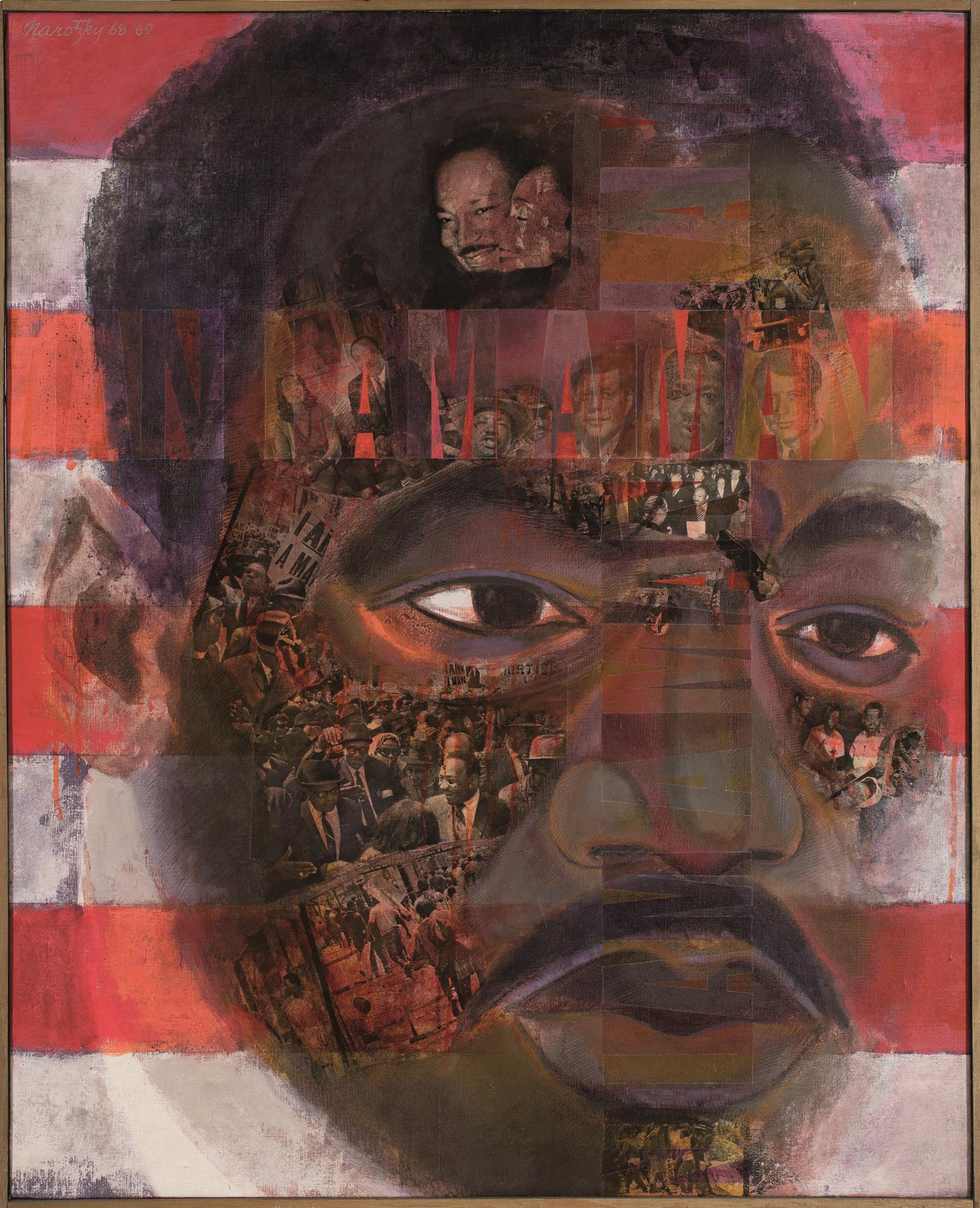

Pim-Pam-Pop, Equipo Crónica, 1971. Collection Rafael Tous. © Equipo Crónica –Co-author royalties Manolo Valdés, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2018

The beatniks first appeared in the United States in the 1950s, and their rebellion was political and sexual, with a tragic air about it. The hippies emerged in the late 1960s, with their romantic aspirations for freedom, peace and getting back to nature. The term “underground” was used especially in the following decade, the 1970s, to characterize the clandestine radicality of the counterculture. The article included the following words by the “long-hairs” who were occupying the squares in the old centre of Barcelona:

- We don’t believe in the realities of the 20th

- Or in space flight, because we still haven’t learned to walk on the Earth – said the one with the red beard.

- Or in wars but we do believe in love.

- Or in socialism.

- Or in capitalism.

- Or in tyrants, dictators and despots.

- Or in the value of money.

- This has been a sort of list of the beat generation’s “credo”. Generation. Protest. And, for that reason, the explanation of why they are outsiders.

These outsiders would be the protagonists (or the symptom, depending on one’s point of view) of profound changes in Western society’s mindset. Obviously, the intellectual and ideological standpoints were far more nuanced, according to whether the context was musical, academic, political or artistic. The late 1960s were a time of banality and revolution, of dreams and repression, of frivolity and rebellion. Art did not just reflect this, but it acted as an agent of it, and, if you will, a place of change.

Art explodes

Strangely, these years characterized by their cultural, social and political intensity have not been studied very much from the point of view of art. If anything characterizes that period in which everything was doubted and the desire was to reinvent everything, it is the great diversity of ideas and forms of expression. Art-forms such as painting, derived from the modern tradition, rubbed shoulders with the appearance of new media associated with novel technologies like video or with the expansion of art towards dematerialization and, beyond that, its definition linked to ideas and behaviour.

Such diverse options have often been analysed separately. Put simply, exhibitions about Pop-art or about the appearance of the new paradigm of conceptual art have been mounted. But very seldom have both been shown together, pointing out the differences in their nature but also the similarities in spirit and context generated by the period. It is also a moment when the barriers between highbrow culture and mass culture were broken down, linked to the society of the media image. This obliges us to include a third element: the influence of popular youth culture or, directly, its creative role in a common objective: to change the world.

To respond to this complexity, to this interconnected diversity, we have resorted to a dual curatorship. The contribution of Imma Prieto, a noted specialist in historic forms of video-art and experimental cinema – and the person responsible for the recovery of the first work of video-art in Spain, Primera muerte (First Death) by Galí, Gubern, Jové and Llena – has been crucial and fundamental. And so, the exhibition connects the different forms of the avant-garde that coincided at that crucial moment: pop, new figuration or psychedelia, arte povera or performance. It was a time of an ethical and aesthetic rethink that materialized in an explosion of creativity. Art merged with comics, advertising, design and music. New, experimental cinema appeared that rubbed shoulders with the beginnings of video-art. New languages were formulated and art and life became one.

Optimism against everything

In the process of preparing the exhibition, in November 2017 the Museu Nacional hosted a round table with some of the artists working in that period, as part of a symposium organized by Pompeu Fabra University (The Theoretical Years, 1962-1979, Editorial Angle, 2018). Jordi Galí, one of the artists rediscovered by Liberxina, said:

“Music was coursing through my veins, it was a determining factor in my painting. The sixties coincided with the period of the Beat generation in New York. I made every effort to buy records from ESP DISK by mail order, something really complicated in Spain at that time. (…) Their catalogue included spoken records by Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, Tuli Kupferberg and Timothy Leary, the great champion of lysergic acid … and all this during the Franco dictatorship. That was one of the things that gave me most pleasure!”

Music as an escape and release; the wish to get to know and connect with the major centres of modern international culture – revolutionary Paris, London, with its fashion and music, the New York of Warhol’s Factory and the California of the hippies – but also the need to rebel against the political poverty of Francoism, inspired, in one way or another, the young artists who we see in the exhibition. Discovering a new sexuality, breaking with the traditional idea of the family, rejecting the perversions of political power, freeing themselves through outrage and jubilation, joy but also intelligence, these are the vectors that drove the longings of a generation. The impressive richness of the works they left makes them quite attractive today for contemporary sensibility. But what makes them most interesting is that, despite half a century having gone by, the problems that they highlight still seem prevalent and relevant to us now.

An exhibition of rediscoveries

The working process for presenting the exhibition LIBERXINA, Pop and New Artistic Behaviour, 1966-1971, has been exciting. The exchange of knowledge and ideas with a specialist like Imma Prieto, with quite a novel view of our recent history, has been fundamental for the richness of the end result. It must be remembered that it is quite new for a museum such as the MNAC, accustomed to more traditional formats, techniques and languages, to have to link video-art, film, contemporary object and the whole range of creativity that Liberxina reflects.

These are works that present new challenges for museums, due to their fragility or their ephemeral nature. Sometimes they are documents or records of actions. Elsewhere, they are works that require participative interaction by the spectator or which come from an appropriation of reality (through objects or mirrors).

And we have moreover wished to reflect an atmosphere, a period, something that goes beyond the specific pieces. The reproduction (in the sense not of a copy but of a new production) of Antoni Llena’s Intervention at the petite galerie in Lleida would be a clear example of this. Llena came while the exhibition was being mounted to draw the shadow of objects that only he saw (he asked for privacy and did not allow photographs). The resulting work is a drawing that had to be protected due to its delicate discretion, to the way it merged and disappeared, with no frame or physical presence. An absent work, the trace of nothingness or quasi-nothingness, that had to be treated like any other art object by a major museum, posing many questions about the status of the work of art and the role of the museum.

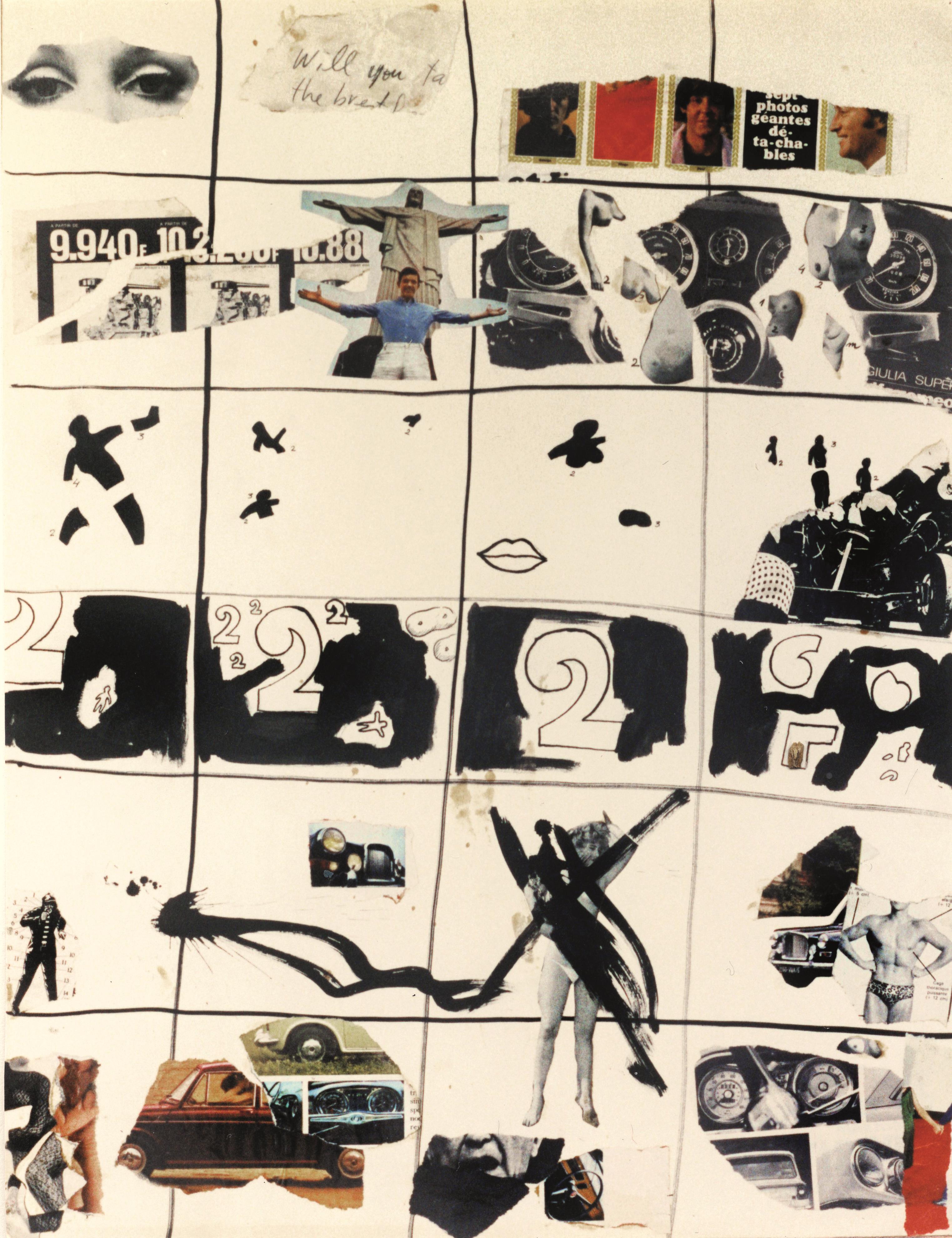

Grid collage, with numbers, cars and The Beatles’, Guillem Ramos-Poquí, 1965. Collection Guillem Ramos-Poquí

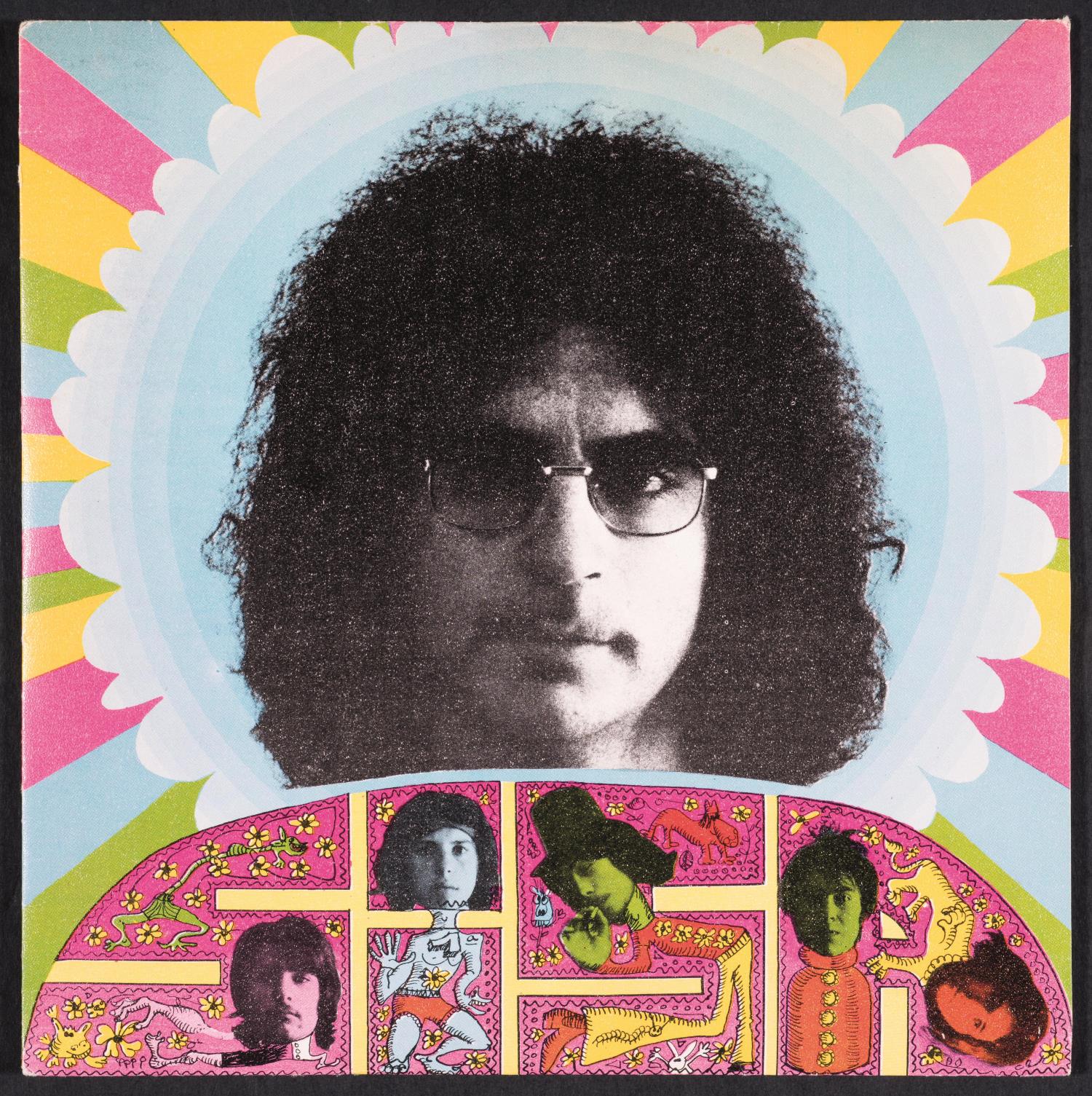

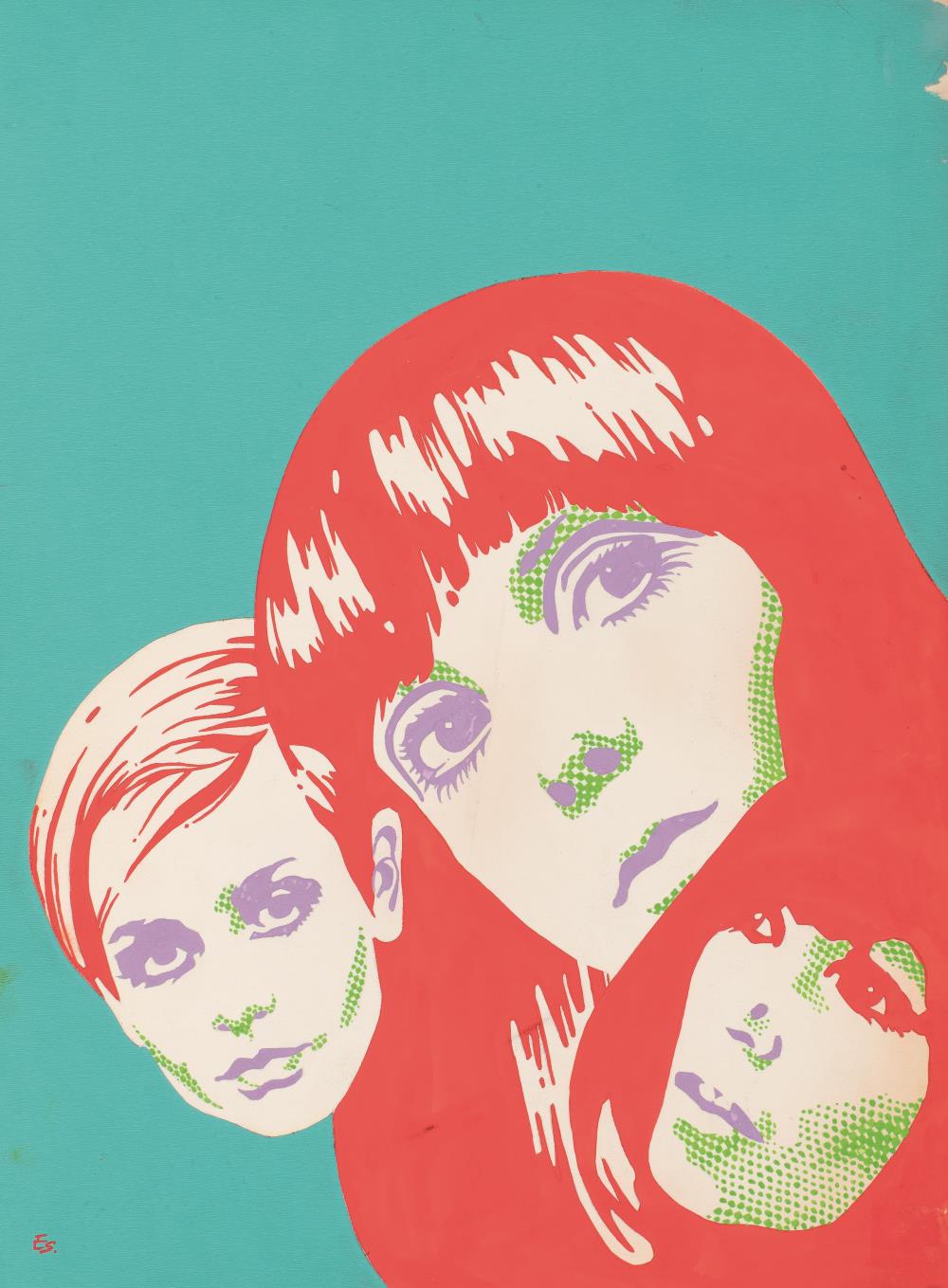

Liberxina makes it possible to rediscover artists like Jordi Galí who, although in some cases they made an important impression on the critics and the artistic community, have over the years disappeared from the front line, or who in some cases redirected their work towards other activities such as design or feminist activism. A remarkable number of works in this exhibition will enter the museum’s post-war and second avant-garde collections (Jordi Galí, Mari Chordà, Guillem Ramos-Poquí, Ernesto Carratalà, Enric Sió, and others). In this way, the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya is entering a period that is history (heritage) but at the same time contemporary, part of the unstable and exciting dynamic of the present.

Related links

LIBERXINA exhibition press dossier (pdf, 8.2Mb)

Art modern i contemporani