Mireia Berenguer i Amat has been working at the Museu Nacional since 2000. She joined as a guide and after going through various departments she is currently one of the documentalists in the area of Collections.

The exhibition on Nonell was the first one she documented. Even though it was finally not put on due to the pandemic, her work was included in the catalogue, which was published. And now she has participated in the Gaudí exhibition.

What role does the documentalist play in the research for an exhibition?

In the case of an exhibition, a documentalist processes and manages the documentary and historical information, in different media and formats, obtained from research in order to facilitate the work of the curator. In the specific case of Gaudí, we started working on the documenting almost two and a half years ago. The curator, Juan José Lahuerta, started from a firm base and with very clear ideas about what he wanted and what he did not want to explain in an exhibition dedicated to one of the most iconic architects in the world.

I was commissioned to gather and organise all the historical, scientific, and technical information related to the work of the great modernist architect, which the curator made available to me and which followed the thread of the discourse he had defined. Once the information was classified, the task of the documentalist really began. First of all, each item had to be located among more than a thousand documents, pieces, and photographs that would form part of the exhibition. This research became complicated in March 2020, when the pandemic brought it to a stop. The remote work and the lack of activity in the cultural sector did not help much, but it is worth noting that the technical facilities that the new technologies provide us with nowadays meant that, little by little, everything started to roll again.

Exhibition showroom Gaudí

What methodology do you follow?

The methodology depends on the needs of the curator and the priorities that the curator fixes. Depending on the information you need to look for, I would start the research in Catalonia and Spain and, if necessary, expand it internationally. There are currently many libraries and archives that have scanned much of the collection and this makes it very easy to make initial contact. Another very complete source that tends to provide a lot of information are the newspaper archives, also digitalised, where you can search through a wide range of old magazines and newspapers, and you can find surprising information. When searching for data on potential lenders, the information provided by the obituaries, for example, is very useful for locating the descendants of some collectors.

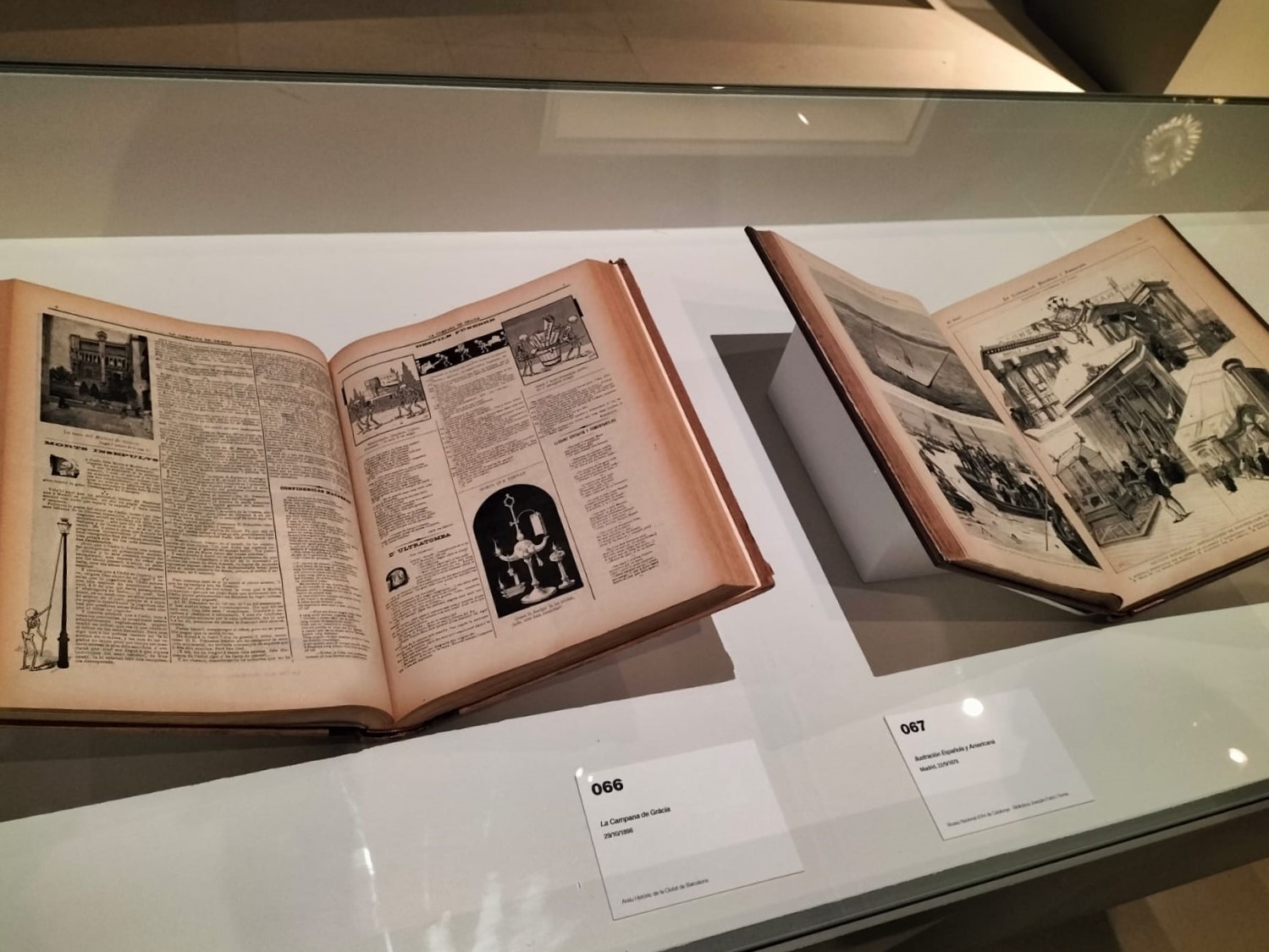

Bibliographic materials from the Arxiu Històric de la Ciutat de Barcelona

What other museum professionals are involved in your work?

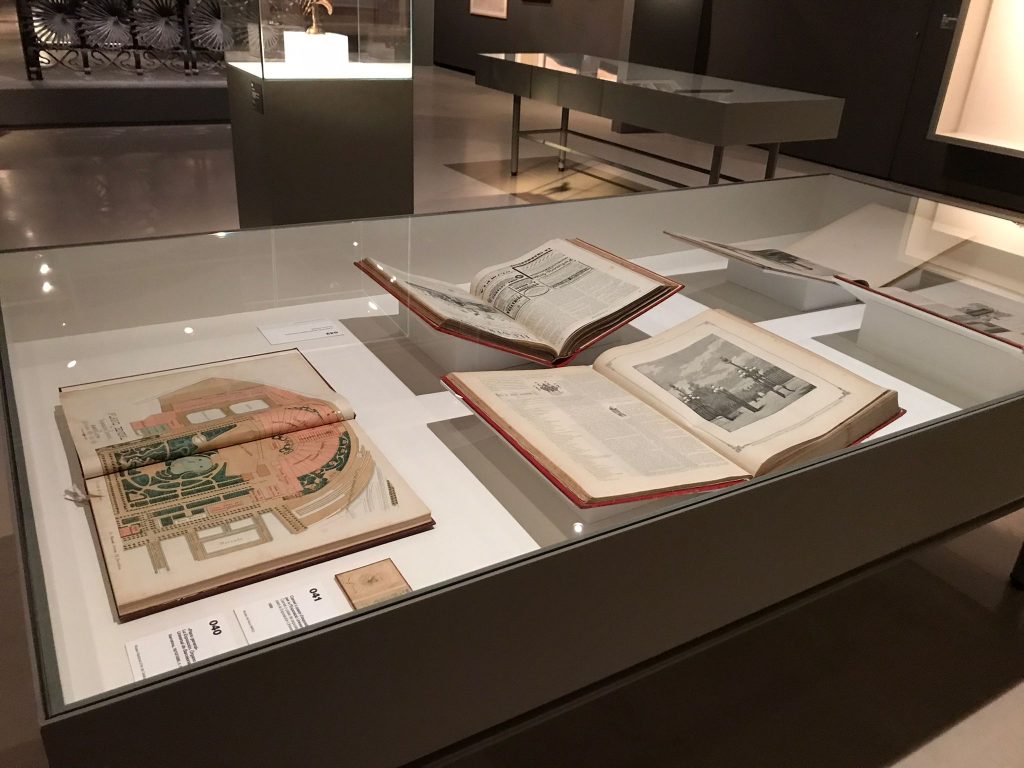

The Museum Archive is often a very key area, as in many cases we need to retrieve information from previous exhibitions that has been collected in the various files that are kept there. The colleagues from the Library also give us their support and, especially in this rich documentary and bibliographic exhibition, their help in locating all this material has been fundamental.

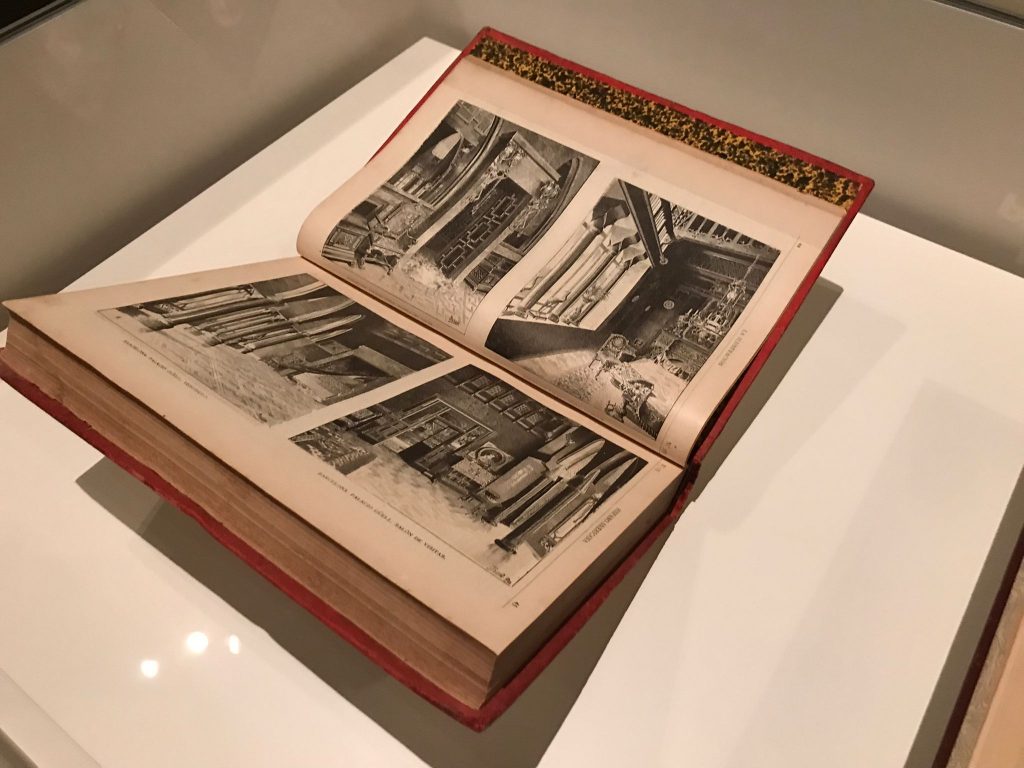

Bibliographic materials from the Library Joaquim Folch i Torres – Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

In this sense, Sandra Herrera, a colleague of the Library, was the one who took on this task and carried it out very effectively. It’s worth mentioning, though, that it was not easy, as they often had to look for old specimens, sometimes difficult to find, and as the exhibition has to travel to Paris in March and the work on paper requires relatively short exhibition time, more than one copy of each had to be located; in short, a titanic task.

Bibliographic materials from the Library Joaquim Folch i Torres – Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

What was the most interesting thing about the Gaudí project?

The most interesting thing was to get to know first-hand the documentary work of the architect, as well as to relate his influences and see how, little by little, the initial project you could see on paper was taking shape. It is a satisfying task during the process of locating the works and because, in addition, sometimes on the way to locating something, others would appear that you were not looking for. When this happens, you let the curator know, and very often those works end up being included in the project.

What surprises have you had? Which materials would you highlight of all those you have treated?

I found a piece of furniture by Gaudí that had never been exhibited because it had always been in private collections. Unfortunately, the owner was reluctant to loan it for the exhibition and in the end the work was not part of the exhibition … what a pity! The other surprise, this time positive, was to find an unpublished photo of Antoni Gaudí in the photographic collection of the Orfeó Català, which the National Archive preserves. This is a sequence of two photos taken a few seconds apart on the occasion of Lluís Millet’s visit to the works of the Sagrada Família. These snapshots were finally chosen as representative images of the exhibition: in the first, Gaudí covers his face with his hat (a gesture that represents him very well) and in the second he can be identified, standing next to Lluís Millet.

Antoni Gaudí in front of the Sagrada Família. September 1920. Documentation Centre of the Orfeó Català

Another fact to keep in mind is the research done on more than four hundred photos of the time, which was carried out in public and private archives to illustrate the exhibition and which, finally, due to lack of space, had to be reduced to a hundred examples.

What was the most difficult thing to achieve?

Undoubtedly, one of the most difficult things to do is to find publications from the time. Sometimes the curator wanted to exhibit a specific page of a certain issue of a magazine and they did not always have the required copy in the library or archive in question. As we said before, paper copies are very sensitive and their exhibition time should be shorter than that of other objects. Therefore, it is necessary to look for two or three copies of each publication, which would allow them to be replaced during the period of the exhibition and could also be present at the Paris exhibition. As I mentioned, the help of our library colleagues, especially Sandra Herrera, has been key to locating everything.

Bibliographic materials from the Library Joaquim Folch i Torres – Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The pieces from public institutions were relatively easy to find, but things got more complicated for the works that were in the hands of private individuals. The private collectors, because of their intrinsic nature, tend to be protective of their privacy and it is not always easy to convince them that the project is worthwhile. Even so, Gaudí is a name that opens doors and it is worth mentioning that almost everyone, on getting to know the project, wanted to collaborate by contributing their grain of sand.

Documentation from a private collection / Antoni Gaudí. Clock frame from Casa Milà, “La Pedrera”. 1909-1910. Private collection.

When does the work of the documentalist finish?

Once the documentation had been compiled, the exhibition had to be designed and the vast volume of information placed on the plan. Due to space constraints, many pieces ended up being left out of the project. From that moment on, and with the list of works defined and on the table, my work shifted towards the support in the management of the information for other departments that then began to work on Gaudí, especially that of Exhibitions, which took on the reins of the project.

Exhibition showroom Gaudí