Joan Yeguas

One of the sculptures of the Museu Nacional which catches the attention of the public is an image nailed to the cross wearing a tunic and with a beard. Despite this description, this is not a Christ in Majesty crucified.

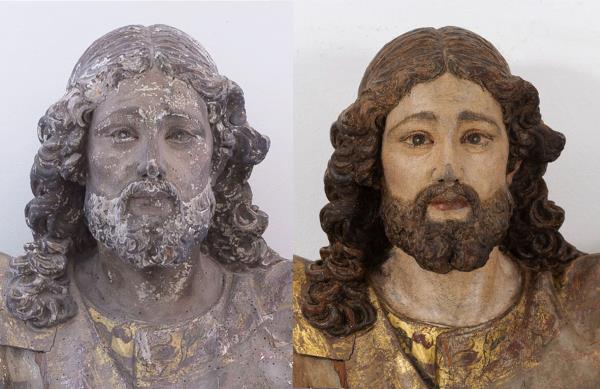

The work was restored by the Area of Restoration and Preventive Conservation, and in this way could form part of the exhibition Baroque artisans. Cervera and the art of its time, organised by the Museu de Cervera between 12th October 2019 and 12th April 2020 (due to the Covid-19 it closed one month early), and jointly curated by Joan Yeguas and Dr. Francesc Miralpeix (professor from the Universitat de Girona).

The sculpture was admitted to the old Provincial Museum of Antiquities in Barcelona in 1879 from the convent church of El Carme in Barcelona, ruled by the Carmelites, which had been demolished five years earlier. This monastery ceased to be worshiped in 1835, due to the Revolts that took place in the Catalan capital; it was finally demolished in 1874. The authorship had remained anonymous until the exhibition Golden Dawn. The art of the altarpiece in Catalonia: circa 1600-1792 (Girona, 2006), when Joan Bosch Ballbona and Carles Espinalt attributed it, for stylistic and technical reasons, to Andreu Sala, one of the best sculptors that worked in Catalonia in the second half of the 17th century.

Saint Wilgefortis or Christ in Majesty?

The work entered the Museum as if it were a Baroque-style Christ in Majesty, and no one doubted it until 1923, when Manuel Trens i Ribas stated the possibility that it was a Saint Wilgefortis. From here, an inevitable debate ensued: Did the work in question represent a man or a woman?

Manuel Trens repeatedly reflects on this image. It didn’t make sense to him that it was a Christ dressed in a tunic, so this typology is related to Romanesque art (derived from the Byzantine world), and not in such a late period as the Baroque. In a later study, from 1935, this historian goes back, and proposes again that it was a crucified Christ, so he thinks that the sculptor takes the model of the Christ in Majesty that until 1936 was in Caldes de Montbuí (Vallès Oriental) based on the argument that he had a similar cloth band crossed over his torso, but that it is actually the fold or the hem of his tunic. But the chest area shows a volume of female features, rather than developed male muscles. In addition, as a result of the restoration, a textile fragment was found at the bottom of the tunic: a stitching work made from lace; traditionally, lace has been a type of decoration used in women’s clothing.

Who was Saint Wilgefortis?

Different martyrologies relate it to the daughter of a pagan king of Lusitania, more or less present-day Portugal. The father had arranged the girl’s marriage against her will, so she had made a vow of chastity because she had chosen to serve Christ, to whom she prayed to disfigure her and thus discourage her suitors. God answered her prayer, making her grow a beard. Her father was horrified by this fact, and after accusing her of witchcraft, he had her crucified, in such a way that she might resemble Christ at the time of his death. It is obviously devoid of any historical reality, and her cult disappeared from the Catholic calendar in 1969 (the most common celebration was on July 20), following the postulates that emerged at the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965). Not to be confused with “Santa Librada“, another martyr who is worshiped in the cathedral of Sigüenza.

The explanations for the growth of the beard in a woman can be multiple: a hormonal imbalance due to malnutrition; suffering from hirsutism (exaggerated hair growth in women following a masculine pattern –there are well-known cases such as Magdalena Ventura painted by Josep de Ribera and currently preserved in the Museo Nacional del Prado-), among others. In any case, Saint Wilgefortis became a protector of agriculture, travellers, children who were stunted or had difficulty walking, skin diseases, pets or the agony of the dying (the good death).

Women also called on her for other issues: the “badly married” to save marriages, and also against ugliness and infertility. With modernity, this saint has been vindicated by other groups, becoming the patron saint of transgender people and a lesbian martyr, because she protected her virginity until her death.

The fact of incarnation of a woman nailed to the cross is said to be a misinterpretation of the iconography, due to the export of the cult of the Volto Santo of Lucca, an 11th century image “attributed” to Nicodemus, which represents a Christ in Majesty. The Byzantine representation of Christ, dressed in a long robe and fitted at the waist, was unusual for European men of that time. The name of the saint has variants according to the place of veneration: 1) Liberated, the virgin liberated by God; 2) Wilgefortis, which is etymologically interpreted as virgo fortis (strong virgin in Latin) or hilgevartez (holy face in Old German); and 3) Kümmernis, the sorrowful virgin, since she resembles Christ suffering on the cross.

The scope of the devotion to Saint Wilgefortis

The beginning of the worship towards Saint Wilgefortis, began in the 14th century in the Netherlands, and then spread to nearby areas of central Europe: first in northern France, it also reached England, and in the seventeenth century it spread to Germany, from where it passed to Switzerland, Austria, Bohemia and Poland. Her veneration in the countries of Mediterranean Europe is more limited. But there is also evidence of it in Catalonia: in the archives of the cathedral of Girona there is an antiphonary from the 16th century with the different festivities, and one of which was this saint; in Collioure (Roussillon) there is news of relics of this saint.

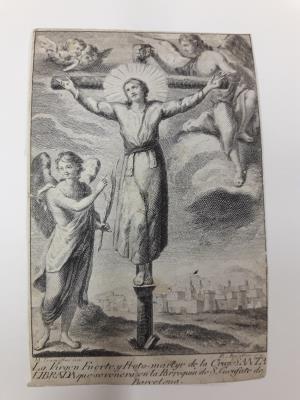

This saint also receives worship in the city of Barcelona, specifically the chapel of Sant Cugat del Rec, where she had a painting dedicated to the main altarpiece (attributed to Manuel Tramulles), and was considered the patron saint of laundresses (who washed in the Rec Comtal). The Museu Nacional preserves prints of this saint from the end of the 18th century, made by Tramulles and Blai Ametller, where we can see a female image in a tunic, but without a beard.

This devotion was collected by Joan Amades in the Catalan Customs (1952), check out the date of 20th July; but on 28th February he also mentions Santa Múnia, with a hagiography completely identical to Saint Wilgefortis (beauty, beard and death on the cross), but born in the Catalan capital. Personally, I think Amades makes a mistake and mixes the story with the other saint of 28th February, who is Santa Guiverada, with a deformed name and clearly derived from Saint Wilgefortis.

Related links

New display of Renaissance and Baroque of the Museu Nacional

Art del Renaixement i Barroc

One comment

[…] A bearded woman crucified: the Saint Wilgefortis of Andreu Sala […]