Mariàngels Fondevila

One of the essential tasks of conservators is restructuring the collection, as well as stimulating its growth, so that it does not stagnate like a Pontine marsh. The museum has reopened the room Modern Life: Photography, Advertising, Film and Design, adding previously unexhibited works, and some newly admitted ones, to those already in it.

Collecting has always been a prime source of our rich heritage and we would very especially like to thank all those who have donated their art works to us for their generosity. These works appear before us as silent witnesses to a period and bring us the expressiveness and creative vitality of the 1920s and 30s, with a certain air of the Avant-garde about them.

In this virtual tour the different arts – painting, sculpture, poster-making, the decorative arts and photography – interact with one another.

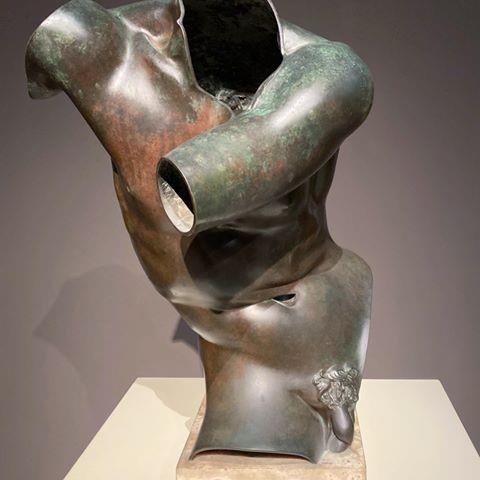

The tour begins with a sculpture, The Crusader, by the unclassifiable Italian sculptor Adolf Wildt, purchased for the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona. It is a torso, in the manner of an ancient statue and archaeological find, in the fullness of its beauty but mutilated, lacking head and limbs, a symbol of the horrors and the tempestuous climate of the early decades of the 20th century, marked by the First World War and the rise of Fascism in Europe. In its classical echoes it exhibits a taste for deformation, perforations and cuts that attracted a young Lucio Fontana, a follower of Wildt’s at the Brera Academy in Milan.

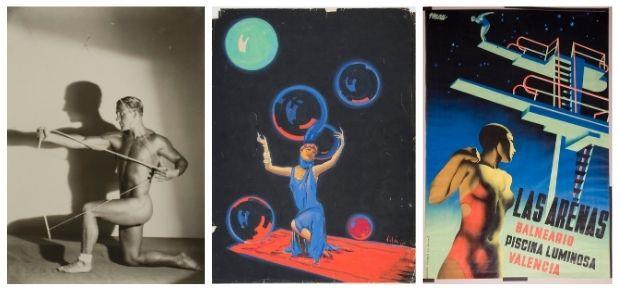

Emili Vilà, Study for poster, 1921

Josep Renau, Las Arenas, 1932

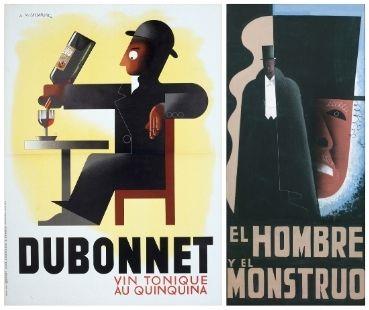

Devoid of tragic connotations and in an Art Deco style, we see the photograph by Josep Masana: a naked archer, quasi-sculptural, like the athletes in Olympia captured by the German film-maker and photographer Leni Riefenstahl with clear references to classical Greece; an advertising poster by Emili Vilà, an artist from Girona who acclimatized very well to the hedonistic Paris of the 1920s, without forgetting the popular poster by Josep Renau, far removed from his committed political gaze of some years later, which extols the healthy values of sport and open-air living. Bathing has ceased to be a cure, a medicine, and has become a leisure activity, as the cosmopolitan magazine d’Ací i d’Allà reminded us in July 1928, while the magazine Imatges pictured Buster Keaton in bathing trunks on the beach in Sitges and organized the contest to choose the Bathing Queen in Barcelona on Sant Sebastià beach.

In those years the aviation industry transformed people’s way of life, and the visual arts echoed the new technological advances. One of its pioneers was the Brazilian Santos Dumont, the first to make a powered flight in his historic 14-bis aeroplane. Dumont, the man of the moment featured on the cover of every magazine, had his portrait painted by François Flameng, an artist far removed from experimental trends who presented this work at the exhibition of French art in neutral Barcelona in 1917 and donated it to the museum.

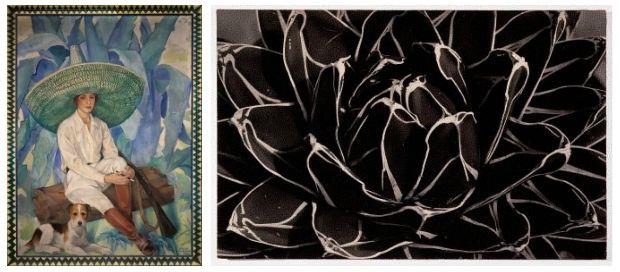

Emili Godes, Cactus, c.1930

Next to the portrait of Santos Dumont hangs a large canvas, in the language of the new realism, by the cosmopolitan painter from Madrid Marisa Roesset (1904-1976). It surprised everyone when it was presented at the 1929 International Exposition in Barcelona, the moment when it entered the Museum, but it has not been exhibited since then. It depicts a horsewoman with a garçonne hairstyle resting, smoking and wearing a large Mexican sombrero. In his diary J. Renart wrote “hairdos and hairstyles have fallen under the killer scissors”. In the background there is a giant cactus, the fashionable plant of the day; its geometrical shapes matched the metal chairs and the nickel and glass tables preferred by the decorators and photographers of the time.

Furniture and interiors

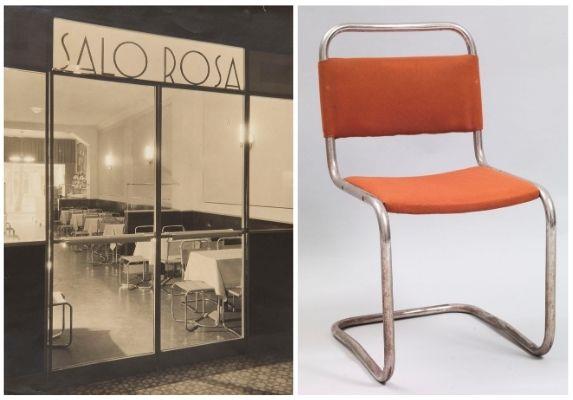

Josep Sala Campàs, Untitled, 1933

Modern decorators and furniture makers no longer gave priority to artisanal skill or the exhibitionist pretensions of Francesc Vidal, who wanted to turn every chair into a throne or a seat of honour. Metallic furniture succeeded due to the quality of its comfort and hygiene. A good example of this is the cantilevered tubular steel chair (without back legs), the authorship of which was disputed between Stam, Marcel Breuer and Mies Van der Rohe, and which entered the museum via a donation. A photograph by Josep Sala from the popular Saló Rosa in Passeig de Gràcia records the presence of these types of chairs.

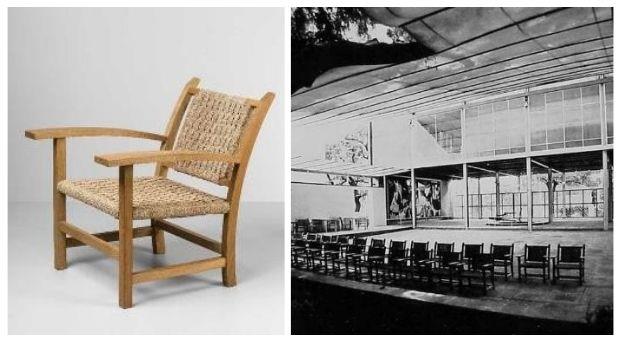

Pavilion of the Spanish Republic 1937

But by the mid-1930s tubular steel furniture was being criticized because of its cold, rather inhuman and inhospitable functionalism. Opposed to the aesthetic of the machine, popular Mediterranean furniture, devoid of stylistic pretensions, was championed. A good example of it is this armchair which has recently entered the museum. Although we do not know when it was made exactly, it is based on a 1936 model by the GATCPAC sold in the MIDVA shop. It is well known that several of these armchairs were, among other places, in the patio of the Pavilion of the Spanish Republic at the 1937 Universal Exposition in Paris. The visitor, comfortably seated, could contemplate Picasso’s Guernica and Calder’s Mercury Fountain.

Ramon Batlles, Untitled, 1933-1936

Esteve Monegal, ‘Maderas de Oriente’ scented cologne by Myrurgia, 1929

New materials, such as rubber and nitrocellulose lacquer coatings, checkerboard parquet flooring (ideal for expelling parasites), or Bakelite, appeared in interiors and objects, for instance the Bakelite bottle Suspiros de Granada by Myrurgia. Some years ago the museum received a generous donation of bottles and advertising photographs, and it dedicated a monographic exhibition to this successful perfume manufacturer and icon of beauty, managed by the Noucentista sculptor Esteve Monegal. One of its star launches was the new presentation of the essence Maderas de Oriente, based on the perfume of cedars of Lebanon, sycamores of Arabia, turpentines of Persia and sandals of Indonesia, with an ergonomic, flat – non-slip – bottle, its stepped shape inspired by Carles Buïgas’s illuminated fountains on Montjuïc in 1929.

Joieria Roca, Brooch, before 1932

Joieria Roca, Necklace/brooch, c. 1935

Josep Sala-Campàs, Untitled, undated

Josep Sala, Advertising Photography for Joieria Roca, c. 1932

Thanks to electric lighting, the streets had become huge shop windows at night where the slogan was: “The light attracts people”. Shops, theatres, bars and cinemas made use of lighting technology, even display cases like the one designed by the rationalist architect Josep Lluis Sert and made by the workshops of J.Ribas for Rogeli Roca’s shop which was donated to the museum by his descendants. Displayed inside it now are the jewels of Rogeli Roca, garnished with platinum, diamonds, coral and rock crystal, which have been deposited in the museum.

Josep Clavé, El hombre y el monstruo (Dr. Jeckyll and Mister Hyde), 1934

The art of advertising

Poster-making, street art, advertising photography and the cinema, which seduced the masses, were also allies of the major companies and mutually fed off one another. The museum conserves a collection from this golden age of advertising that has grown with donations and purchases.

In another order of things, as Pere Català Pic asserted in his writings, photography had to be governed by a new concept of beauty expressing modern life, and it should no longer be interested in models such as a flock grazing peacefully under the watchful eye of a shepherd, or a Modernista composition featuring a nymph dressed in tulle under the shade of a poplar tree.

Manuel Capdevila, Brooch: Iris, París, 1937

Josep Granyer, Ramon Sarsanedas, Laca Sakura, Circus Man, c. 1930

Laques Sakura, Josep Granyer, Ramon Sarsanedas, Flamenco singer, c. 1930

Enriqueta Benigani, Mercado de Calaf Screen, c. 1929. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Object-based arts

New admissions have made possible the presence of lacquer in the material in the collection, with sculptures by manufacturer Laques Sakura with a new concept of more geometric beauty devoid of ornamentation in correlation with the dominant new Art Deco aesthetic trend. A screen by Enriqueta Pascual Benigani has also entered which reproduces a design by Xavier Nogués originating in picturesque Catalonia, a work that ought to be the subject of a more profound study. Years ago, the jeweller Manuel Capdevila donated a well-known set of lacquered brooches that have gone round the world and are currently exhibited in the section about the Civil War.

Jaume Mercadé, Coffee set, c. 1925

Ramon Sunyer, Cutlery set, hacia 1918-1920

Jaume Mercadé Queralt, Bracelet, 1930

The descendants of the precious metalworker Ramon Sunyer also made a donation of objects for everyday use – a set of cutlery and a mirror – in a refined and functional style, without forgetting the Art Deco furniture from the shop in Gran Via, which is currently being prepared in the Restoration Department and will be exhibited shortly. We celebrate the incorporation of new pieces of jewellery and silverware by Jaume Mercadé, especially the silver coffee set with rosewood handles in which the painter-jeweller abandoned his nostalgia for past styles and threw himself into the spirit of the new modern times. Mercadé, like many of the artists mentioned, took part in the 1925 Decorative Arts Exhibition in Paris, a show that set out to forget the past and bid the final farewell to Modernisme (Art Nouveau), considered by some to be a fin-de-siècle aesthetic pandemic.

Art Modern i Contemporani