Francesc Quílez

The Battle of Tetouan, an excessively uncomfortable commission

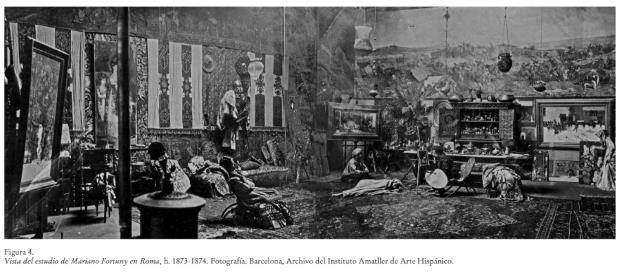

The Battle of Tetouan remained abandoned, half-finished, and became one of the most emblematic images in the studio that Fortuny had turned into a house-museum in the city of Rome in order to house his collection. The object occupied, as a decorative frieze, a preferential space on one of the walls of this place. Despite its prominence, photographs in the Roman studio allow us to venture that, at the time they were taken, well into the 1870s, the painter had definitively given up on pursuing a task that, as we know, was at the mercy of the few occasions when he had seen fit to express his opinion, he was overcome by it and it had become a difficult burden to bear.

With good reason, the passage of time had increased this feeling of carrying a huge burden and had brought into question his supposed determination. On the contrary, what it revealed was his inability to take on a challenge that, unintentionally, had reached colossal proportions, far superior to the skill and capacity of a painter who, in our opinion, was much more used to taking on commissions of much smaller dimensions and with which he always felt much more comfortable. As time passed, far from reconciling with it, the uneasiness increased and the onerous commitment turned into an authentic nightmare, a burden that he needed to get rid of, and to feel liberated, despite the moral bond he always felt.

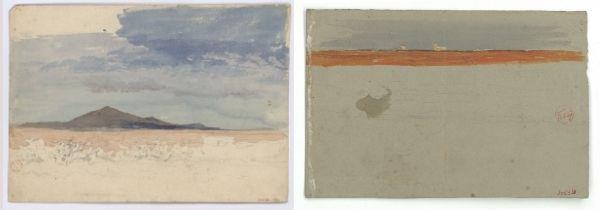

Paradoxically, the increase in difficulties, to which the maintenance of creative tension subjected him, did not imply a decline in his strength, in his ability to resist and to find moments of great poetic lucidity, brief parentheses that were translated into episodes of a high qualitative level. In this case, we can say that the anxiety to complete the production of the grand machine found its most appropriate remedy in some preparatory drawings that reveal a prodigious talent and a desire to explore new paths. In general, these are landscape studies, most of them carried out in watercolour, in which we discover two realities: on the one hand, a surprising, unexpected ability to work outdoors and to obtain luminous effects of great brilliance in open settings, subject to the unpredictability of atmospheric changes.

It is an unexpected discovery that brings us closer to a new aspect, that of landscape painter, which highlights the versatility of the author, in a genre to which, traditionally, he had not usually been defined for.

On the other hand, as an aspect that connects with our approach, many of these works were half finished, they were not completed, which accentuates the impression that we are facing a type of experimental exercises, in which the painter glimpsed the possibility of feeling freer and took the opportunity to delve into the search for new creative stimuli, such as a journey that ran parallel to the obligation to finish the painting of history.

It is also possible to think that the painter’s own evolution and his preference for a typology of works, of a very different nature, was distancing him from a commission that was not pleasant for him and to which only sentimental motivations continued to be linked. In fact, far from frequenting large-format productions, adapted to conventions, models and academic impositions, Fortuny oriented his professional activity towards specialising in the production of cabinet paintings, following the fashion of small-format works, the ones known with the French term tableautin, which were best suited to the tastes and demands of a growing market.

However, despite opting for the use of smaller formats more adapted to his exquisite technique and his skills as a consummate specialist in obtaining brilliant aesthetic results, he did not find the desired satisfaction in these types of works either.

The Spanish wedding, a work that brought him difficulties

Without looking any further, the case of the famous The Spanish wedding a work subjected to continuous ups and downs, to changes in planning and to the tensions inherent in a story open to the inclusion of different compositional resolutions, is paradigmatic and allows us to glimpse some of the causes why, from this episode, and contrary to expectations, he began to show more doubts than ever

Interestingly, the completion of The Spanish wedding and its subsequent presentation in society, in the spring of 1870, at the Parisian gallery of Goupil, despite definitively catapulting him to fame, it involved a great emotional upheaval, it meant leaving many shreds of skin along the way, and opening a deep wound that took a long period of time to heal.

After all, and against all odds, Fortuny, after achieving great success, made the radical decision to cut himself off from all the noise, from the fame that the public presentation of the work brought him. In this sense, the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian war gave him the opportunity, the pretext he needed, to make the intentions come true, something which he had already caressed, for a long time, of distancing himself from a dynamic that, although it had allowed him great recognition, an honorable reputation, at the same time, had led him to open an ever-deepening gap with the orientation of his own creative instincts and with personal interests that increasingly moved further away from the framework of bourgeois artistic relationships.

Granada: Fortuny comes to terms with himself

This ambivalence manifested itself in the appearance of an insurmountable barrier that ended up making irreconcilable, on the one hand, the desire to satisfy his artistic concerns and, on the other, the reality of a market, with a great commercial voracity and eager to consume a certain type of artistic goods, which forced him to make concessions, to renounce his most personal emotions and desires.

In this sense, as he himself reflected, through his brief correspondence, the trip and subsequent stay in Granada, between 1870 and 1872, became the best refuge, the repairing balm that helped him start a process of coming to terms with himself, of overcoming a dynamic that far from satisfying him, had caused him great dissatisfaction both personally and professionally. Not in vain, during this stage the number of unfinished works grew and the need to reflect on the meaning of creative experience became more explicit. The interrupted productions began to be as numerous as the finished ones; a situation that came to alter the order of a system that until that moment had hardly shown weaknesses.

Despite what we have been saying, we think it would be a mistake to interpret that before the stay in Granada, the painter had been subjected to a kind of inexorable fatality, a curse. Without denying, at all, some of the previous arguments, we believe that before this stage, Fortuny already had the need to pass through more open spaces, to explore other paths and that, in this sense, the ambulatory process of making The Spanish wedding already contained, in itself, the seed of liberation, the desire to experiment without being conditioned by the final result. In our view, this experience was liberating because it allowed him to work according to the orientation of his own instincts and impulses.

However, Fortuny’s most iconic painting, the one that has contributed the most to making him a symbol, with all its advantages and disadvantages, did not reflect the background of a long creative process in which drawing held a prominent place and in which the painter was adapting the artistic idea, managing to produce a large number of sketches, and even scratches. The comings and goings, the changes of direction had their crystallization in the gestation of a first version, currently unaccounted for, which has little to do with the one that can be seen in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

In it emerge, with apparent conviction, the most stereotypical characteristics of a shop window painting in which all the visible elements are shown before our eyes as coveted, luxurious and shiny objects.

A very dynamic process of artistic creation

Far from resigning himself, or accommodating himself to the circumstances, on many occasions, Fortuny maintained the tenacity, the constancy and amassed enough energy to continue, with care, dedication and commitment, many of those works that passed through unexpected twists and turns and were developed under the dynamics of a syncopated rhythm, tracing the drawing of a broken line in time.

The doubts, the hesitations, the regrets, the toing and froing, the changes of approach, were aspects that were very present in his way of understanding artistic creation, as a dynamic process. Even in some works, which could be considered finished, the doubt arises, if we carefully contemplate the work and observe how, in some cases, forms modeled in a precise and detailed way coexist, in the same composition, next to schematic lines formed by silhouettes of figures, or by brush or pencil gestures, which generate a very disconcerting sensation and which raise a reasonable doubt in the viewer about the state of the composition. In this regard the Granada Landscape, an unfinished production, could be highlighted as one of the most paradigmatic cases of a painting in which the pictorial masses that reproduce a place in the city are invaded by disturbing and disconcerting reasons, such as the appearance of an animal’s head, perhaps a lion, and the silhouette of another, emerging in the middle of a street where a person seems to be walking, whose identity is not revealed to us. Without a doubt, these are two whims, two inventions that corroborate the existence of a fertile imagination.

Not surprisingly, some of these details are only open to our vision if we make an effort of attention, or an exercise of visual acuity that forces us to hold our gaze on those aspects that, in a first vision, we have not been able to perceive and that have passed us unnoticed.

Precisely, this meta-pictorial condition, or the creation of several plots, in the same story (note the detail of the painting that appears in The Spanish wedding or the tapestry that is discovered as the background of The print collector) that we find in many of his productions, is one of the most interesting aspects of his poetics and is one of his main strengths, the one that allows him to transcend the historical time he had to live to project himself as a current artist, endowed with a sensitivity, of a mentality that has an absolute validity today.

In this sense, the unfinished works transmit this situation of lack of definition, they open a gap between what could have been and what in the end was not. Along the way, many illusions, desires, hopes are abandoned, which can generate a natural frustration, but can also be understood as accessory circumstances of a more iron will to climb to the summit, being aware that the resignations, to which one is obliged, end up being part of the accidental nature of the pilgrimage that he had decided to undertake.

Final reflexions

In short, in this process, the route that the artist takes along the path he has undertaken has as much or more interest, although this journey is uneven and winding. The itinerary itself, takes on a very stimulating creative dimension because it becomes the true metaphor of a very dynamic creative process, in which the artist discovers new possibilities, options, challenges that require ingenious solutions and that force him to maintain a vigilant attitude, awake and open to the incorporation of all the discoveries that he is making while making this uncertain journey that, far from offering him assurances, causes uncertainties and insecurities and forces him to question himself, to shed a visual baggage that does not allow him move forward.

Beyond this desire, or some expectations, not always satisfied, there is also an underlying will to keep the creative tension alive, which causes doubts, hesitations, concerns, or a need to rethink the usual way of approaching the creative process.

The acknowledgement that there are no magic recipes, simple solutions or accommodating proposals, represents a clear example of how a painter who has managed to achieve social recognition and economic success, far from settling into a resigned or well-off attitude, one that allows him to live without too many ups and downs, and installed in a comfortable position, adopting a conformist attitude, decides to renounce the advantages of this situation to enter into a dynamic of permanent change that leads him to maintain a high level of demand and to carry out a constant renovation.

In this framework of action, the unfinished productions would become a field of experimentation, by allowing greater expressive freedom, far away from the conditioning that leads to a certain syndrome of repetition of the most commercially successful visual formulas, those that have guaranteed a certain recognition, but that do not allow you to feel satisfied.

Related Links

“Non Finito”. Fortuny and the paradox of the perfectionist /1

Fortuny’s Carmen Bastián: problems with its reception and interpretation

Marià Fortuny: painting as the representation of a worldview

Fortuny 1838-1874. Exhibition catalogue

Scenes of creation: artists’ workshops / 1

Scenes of creation: artists’ workshops /2

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats