Pilar Vélez

Vittoria Colonna was a woman with a great personality, a poetess, and according to some authors, “the most famous woman in Italy”. On one hand she was the daughter of Fabrizio Colonna and Agnese da Montefeltro, and the granddaughter of Federico da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino. And on the other, she was the marquise of Pescara, through her husband the marquis, the Neapolitan Francesco Fernando d’Àvalos. The son of Alfonso d’Àvalos and Maria Hipólita Diana of Aragon and Cardona, he was from a family loyal to the Crown of Aragon and Naples, and she was married to him at the age of 16.

The Colonna family, allies of the D’Àvalos family, agreed to the marriage when the couple were still children. They were married on 27 September 1509 on the island of Ischia, in the bay of Naples, in “Aragonese castle”. This, as a property of the Aragonese royal family, passed into the hands of King Ferdinand the Catholic, who, out of gratitude to Íñigo d’Àvalos for his staunch defence against the French, granted the government of the island to this family.

Despite being an “arranged” marriage, it seems that they loved one another. Her husband, however, had to go off to war, under the command of Fabrizio Colonna, to fight for the emperor against France and he left the island. Taken prisoner at the battle of Ravenna in 1512, he was taken to France. He later became an officer in the army of Charles V and was badly wounded at the battle of Pavia on 24 February 1525, where Francis I’s army was defeated. Vittoria hurried to be reunited with him in Milan, but before she got there she learned in Viterbo that he had died. Very upset, she withdrew to a convent in Rome, a very important event for her, as there she befriended several ecclesiastics who promoted a reformist current within the Catholic Church, including the Spanish follower of Erasmus Juan de Valdés. This was crucial for Colonna – a great disciple of his – although she returned to Ischia and thus avoided the sack of Rome on 6 May 1527. However, imbued with the new religious spirit, in 1531 she went back there. In 1537 she went to Ferrara and in 1539 she returned to Rome, where she met somebody who was to become a great friend of hers, Michelangelo Buonarrotti, with whom she shared the commitment to religious reform. Colonna was persecuted by the Inquisition – the reason why she always lived in convents – above all for being a firm champion of the “rules” of Saint Francis, opposed to Catholic orthodoxy.

Her most outstanding literary work are the Rhymes – some of which are profane and amorous, dedicated to her late husband, as well as the sacred ones – which reveal the influence of Petrarch. The first edition, in 1538, was printed in Parma, but 19 editions were made of them in the sixteenth century.

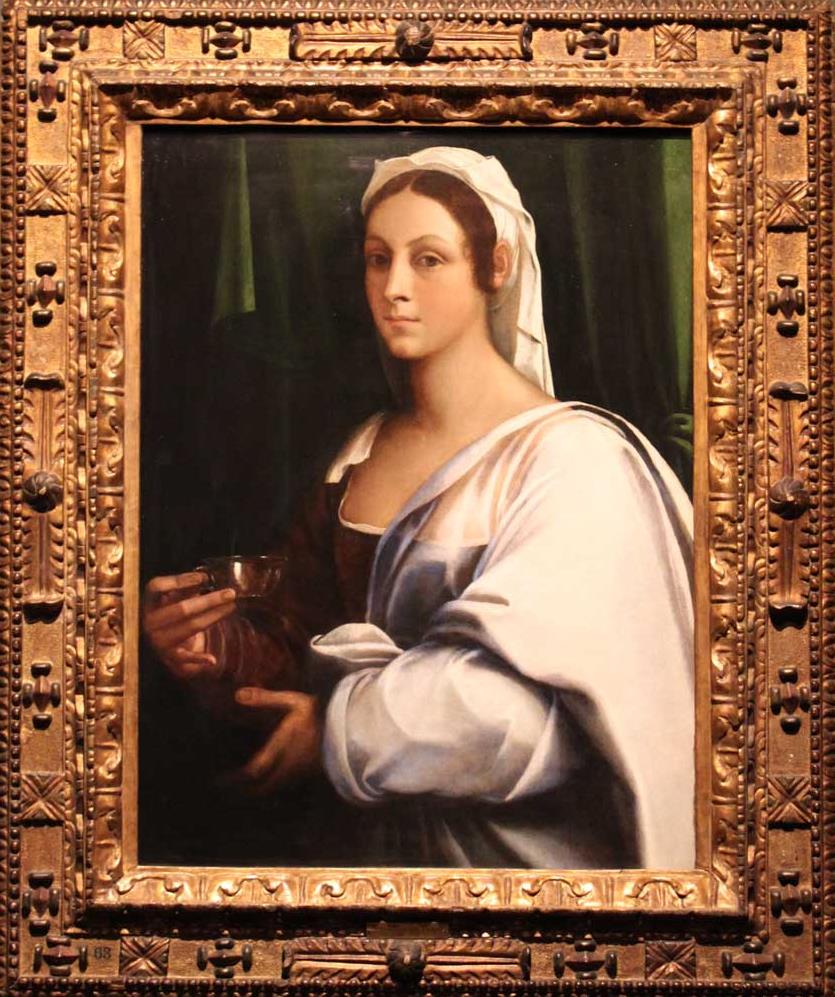

Two portraits of Vittoria Colonna, painted by Sebastiano del Piombo

Several portraits of Vittoria Colonna have survived. The portrait painted in oils on wood in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, up to now dated by the museum to 1520-1525, is the work of the Venetian painter Sebastiano del Piombo, or Sebastiano Luciani, who among other things was a friend of Michelangelo. There is also another very similar portrait by him, but in this case the figure is holding a small cup in her right hand and there is no landscape incorporated. It belongs to the Harewood Collection in Leeds (UK), one of the great European collections of Venetian painting.

The portrait in the Museu Nacional is from the Cambó Bequest (1949), considered the most important disinterested contribution that the museum has ever received. It entered in 1954 – the bequest arrived there between 1949 and 1954.

The Vittoria Colonna from the Cambó Collection

The sitter is looking straight at us. She is dressed very austerely: she is not adorned with any jewellery – no earrings, necklaces or rings. She doesn’t need them. She is a woman who transcends the appearances of rank, and the image shows us a solid personality. Even the dress, in an embroidered material, typical of the fashion of those years, is simple. She is wearing a white veil on her head and a headscarf, also white, over her shoulders. This seems to suggest that she was a widow, of a “Franciscan” simplicity present in her ideas and her image. The neckline is low, in the Renaissance manner, or “Roman-style”. The index finger of her right hand is on the neckline, a detail that seems to allude to her depth of spirit. Meanwhile, with the index finger of her left hand she is pointing to an open book, of poems, perhaps the Rhymes she dedicated to her husband. On the table there is an eastern tapestry like the ones that were common in Europe at the time, visible in many other paintings like those of Johannes Vermeer.

If all this is true, it suggests that this portrait of Colonna ought to be later than 1525, since that was the year her husband died. But we are still studying it. The background of the portrait is a landscape, a habitual resource in paintings of that period and in Piombo’s work. We are wondering if it is a stock landscape, purely decorative, or a landscape that tells us something about the sitter.

Castle. Wikimedia Commons. Public domain

Revising a great deal of graphic documentation on the places that were important in Colonna’s life, it seems plausible that the building in it could be the tower of Aragonese Castle, and if you look closely you can even make out the mast of a ship near the shore. Therefore, it could well be Aragonese castle – still known by that name today – on Ischia, where the young couple were married, depicted by the painter in memory of her beloved husband, with her dressed as a widow.

The portrait, therefore, could have been painted in Rome shortly after the death of her husband, or perhaps even more probably when she returned to Ischia in 1527. This may well be a likely hypothesis.

Related links

New display of Renaissance and Baroque

Curiosities of the collection: Renaissance and Baroque

Four stories from the Renaissance and the Baroque