Eduard Vallès

There are characters who, without much fuss, appear behind countless cultural projects. One of the most solid cases in Catalan art is that of Miquel Utrillo, whose work had effects on heritage, art criticism and cultural initiatives of all kinds and the most difficult to measure, as the transmission of ideas or the creation of intellectual networks are not always truly defined or, all too often, end up being patrimonialised, so to speak, by third parties. There are other character who, without having the activist spirit, and even less so the erudition of Utrillo, ended up playing a relevant role, as is the case of the photographer, art technician, artist and collector Joan Vidal Ventosa (Barcelona, 1880-1966).-

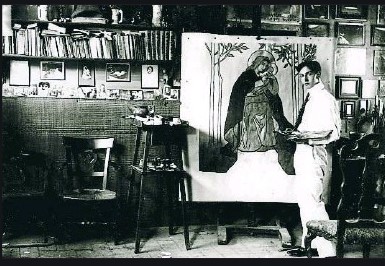

If we analyse his biography in perspective – in this case the one we know of, which is little, it turns out that he moved around some key spaces and moments of Catalan art of the twentieth century. Some important milestones include his status as the founder and soul of El Guayaba; his side as an artist and as a pyro-engraver, and, above all, his work as an art technician and photographer in municipal museums.

As a photographer, his work as a photographic chronicler of the disembowelment of old Barcelona that would give rise to the current Via Laietana, which, by the way, was the same reform that would demolish the mythical Guayaba, first located in the Plaça de l’Oli and later in Carrer de la Riera de Sant Joan; the campaign to start Romanesque paintings in the churches of the Pyrenees, or the campaign to save the artistic heritage during the Spanish Civil War, among many others. It’s not a trivial matter. But it is also necessary to highlight his role as a patron of municipal museums, a lesser-known aspect, with donations, modest, it should be said, to museums such as Picasso or the Museu Nacional.

An important period is his relationship with Picasso from the time of the Quatre Gats (the Tavern) until the 1960s, when he played a role in the creation of Picasso’s monographic museum in Barcelona, but this is not the reason for this article. If his strict work as an art photographer would already be enough for a monograph, his life, due to the diverse registers he worked on, would possibly justify a doctoral thesis. However, this article will only revolve around a couple of his photographs, without going any further.

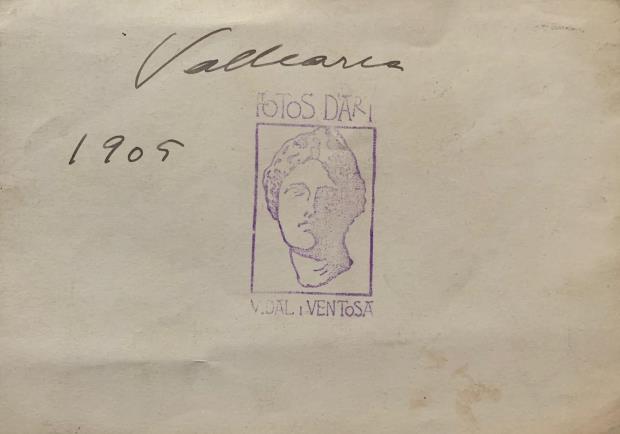

Vidal Ventosa and Vallcarca

A photograph by Vidal Ventosa has recently entered the collections of the Museu Nacional, which is related to a work from the permanent collection of modern art. This is a snapshot taken in 1905 that represents a partial black and white view of the Vallcarca district. On the back is the unmistakable stamp of the photographer with his surnames (“PHOTOS OF ART / VIDAL Y VENTOSA”) accompanied by his classic female bust. Next to the stamp is written, in pencil, the word “Vallcarca” and a date, “1905”, most likely by the hand of Vidal Ventosa himself.

In principle, this image is nothing special, until we realise that it is exactly the same frame as a work by Vidal Ventosa from the Museu Nacional. This refers to the pyro-engraving Vallcarca on a moonlit night, currently on display in Room 69 of the permanent collection of modern art. The photograph dates back to 1905, so it is slightly earlier than the date of execution of the pyro-engraving, between 1906 and 1907, which is why it is very possible that Vidal Ventosa had done the pyro-engraving from this photograph or a similar copy.

Vallcarca on a moonlit night was included in the 5th International Exhibition of Fine Arts and Artistic Industries of 1907, which took place at the Palau de Belles Arts in Barcelona, and was donated by Vidal Ventosa himself to the municipal museums in 1964.

This effective pyro-engraving stands out for its unique frame, most likely from the hand of the artist himself. The work is an original night-time view of the neighbourhood, which projects the effect of moonlight on the central part. It is clear, although he worked from a black and white image, that it was the artist who devised the original chromaticism, as well as a careful simplification of the spaces. Vidal Ventosa sublimates the space that was then semi-urban, somewhat un-poetic, to endow it with a dreamlike, almost timeless condition. For the chronology and aesthetics, this work already highlights some of the principles that the noucentisme would include that, just around 1906, Eugeni d’Ors was beginning to put down in black and white. Vidal Ventosa’s career as an artist – in fact, he is rarely mentioned as such, but as a photographer – did not go much further, as although some of his pieces are known, none of them have the personality of this pyro-engraving. For many years it went unnoticed until Alexandre Cirici praised it in El arte modernista catalán in 1951: “Vidal Ventosa monumentalised the pyro-engraving with his large painting Vallcarca on a moonlit night”. But his canonisation in expository terms would come when it was exhibited at the legendary Exhibition of Sumptuous Arts of Barcelona Modernism, which took place at the Palau de la Virreina in 1964, curated by Joan Ainaud de Lasarte.

Currently, the real space of this pyro-engraving is occupied, in its left part, by the bridge of Vallcarca, that began to be built three years after the photo by Vidal Ventosa, in 1908. In an article which vindicated heritage in the magazine El Temps (“Neoclassical remains”, 22/12/2009), Dr Francesc Fontbona referred to this same pyro-engraving, warning of the impending demolition of the most central building in the composition. As an illustration of his article, Fontbona was still in time to reproduce a recent photograph of the house, already badly destroyed. Another photograph taken on the occasion of that article shows the bridge and, to its right, the house in ruins just prior to being demolished. What is most relevant of all is that this photograph allows us to sense what the work method of Vidal Ventosa would have been, by using the technique of photography, of which he was already a virtuoso at the time. We think that he would have done others, given that the some cypress trees appear in the pyro-engraving that are not in this photograph, but they can be seen in old contemporary photographs of Vallcarca.

The ties of Vidal Ventosa with the Museu Nacional

If we focus exclusively on Vidal Ventosa’s relationship with the Museu Nacional, his work as a patron is less well known, as he would end up making various donations, not only of his works, such as the pyro-engraving, but also of other artists, which are currently in the Museu Nacional.

He is also linked with the museum as a municipal photographer who immortalised many of the works in its collections. Apart from his regular work in museums, due to its historical significance, it is worth highlighting, among so many others, a couple of episodes linked to our artistic and architectural heritage: the photographs which document the tearing down of Romanesque murals; the photographs taken during the process of safeguarding the artistic heritage during the Spanish Civil War.

In the second case, these are photographs, many of which being quite well known, taken in spaces such as the Palau Nacional, the Palau de la Ciutadella, the church of Sant Esteve d’Olot or various buildings that were enabled at that time to manage the art collections, among others.

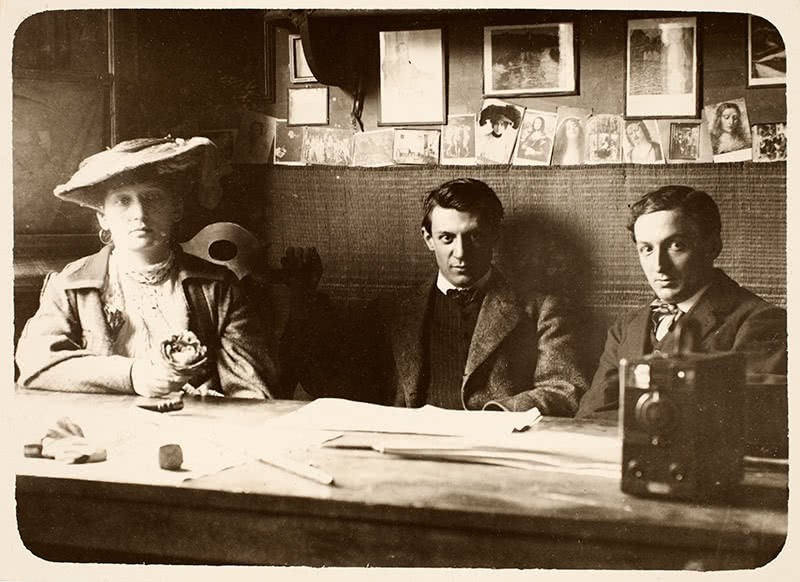

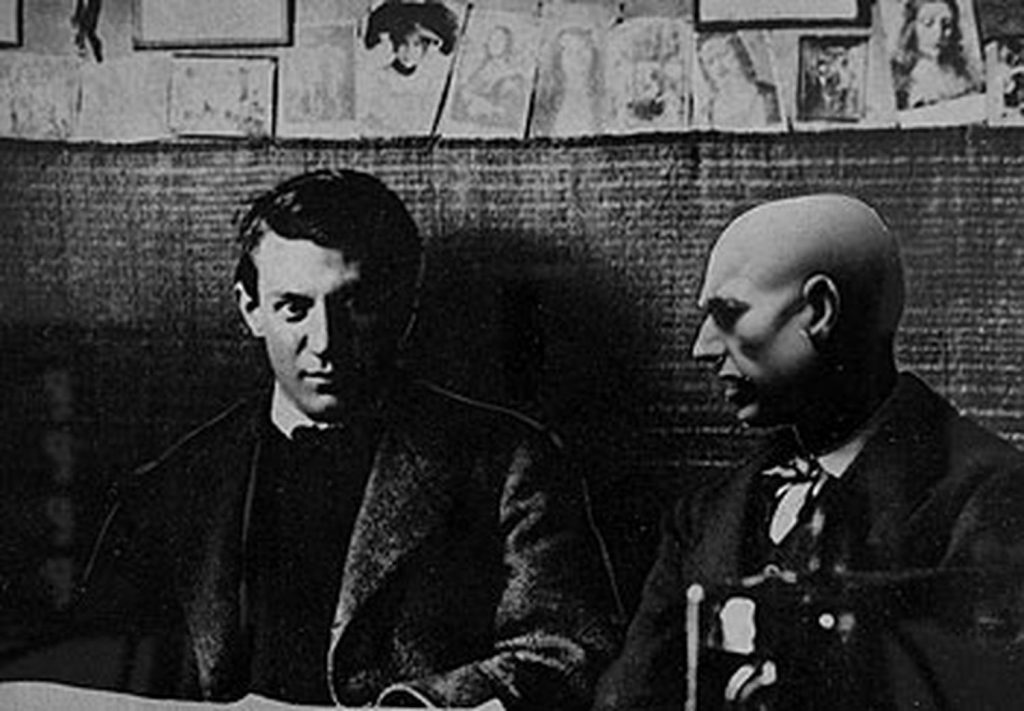

The Museu Nacional also has a period copy of the most universal snapshot ever taken by Vidal Ventosa. This is Picasso’s photograph at El Guayaba, the famous cenacle of young artists and intellectuals in the no-longer Plaça de l’Oli, of which Vidal Ventosa was one of the souls and its tenant, as Rafel Torrella explains in the article “El Guayaba de Vidal Ventosa” (Revista de Catalunya nº.71, 1993).

This photograph is one of the very few known images of Picasso in Catalonia, where the artist is seen sitting inside the premises, between his French partner Fernande and the writer and journalist Ramon Reventós Bordoy. In the background, on the wall, there is a corrugation of reproductions of works of art: the portrait of Joan Maragall by Ramon Casas, that of Erasmus of Rotterdam by Hans Holbein, the Three Graces by Rubens or a photograph of Cléo de Merode, among many others. Thanks to Palau i Fabre, we know that this photograph was taken at the end of May 1906, to be exact on the eve of Picasso’s departure for Gósol, as the artist himself explained to Palau. By comparing the date of the execution of the pyro-engraving and that of this photograph, we are assailed by the doubt as to whether Picasso would have come to see this pyro-engraving in his friend’s studio, as it is very probable that he was working on it on those dates.

This photograph, amply reproduced, was used by Max Aub many years later to document the fictional character Jusep Torres Campalans. Aub invented an artist, Torres Campalans, a biography and a work, in a fictional story about certain aspects of avant-garde art. In the elaboration of this fake biography of a Cubist artist —born in Mollerussa and died in Chiapas, he took advantage of Vidal Ventosa’s photograph to give him a physical identity and, at the same time, place him next to the maximum reference of the avant-garde, Picasso. Josep Renau was the one who made the photomontage, which consisted of cutting the photograph by Vidal Ventosa in the middle and replacing Ramon Reventós with Torres Campalans, an image that was published in a book by Max Aub the title of which being the name of the invented artist.

It is curious that the two creations that have made Vidal Ventosa transcend the most – with the exception of the photographs mentioned, of enormous value, were both produced around 1906, at the age of twenty-five or twenty-six, when he still had to live sixty more years. With Vallcarca on a moonlit night, he would enter the history of Catalan art and, with the mythical photograph of a satisfied and relaxed Picasso in El Guayaba, a universal viralisation would be ensured which, unfortunately, was not always accompanied by a recognition similar to its creator. Both works have in common the fact that they immortalised two spaces of memory, El Guayaba and the old Vallcarca, both demolished by pickets. There is nothing left of those places, but thanks to the work of Vidal Ventosa, we have received one of the most suggestive artistic views on Vallcarca and what is probably the best photograph of Picasso’s youth.

Related links

Joaquim Mir & Picasso: Portraits, wild and solar

Casagemas, vindicated. History of a long research and of an exhibition

Art modern i contemporani