Francesc Quílez

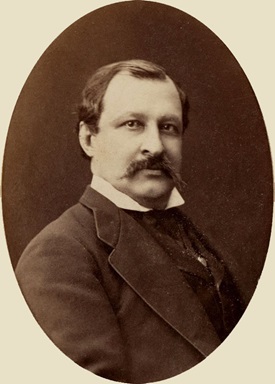

I mentioned in part 1 that I would analyse some of the details associated with the process of creating this work. The aim is to resolve some of the unknown factors to do with the historical context in which it was made. To begin with, I can state that my first hunch, which led me to suppose that the painting was done during Fortuny’s period of activity in the city of Granada, between 1870 and 1872, has been borne out by the documentary information I have been able to find.

Two Beggar Women, a work from Fortuny’s Granada period

Before discussing the results of the investigation, I would like to go into the reasons that led me to think this was a painting made in Granada. For this I based myself on formal, thematic, compositional and also figurative aspects. The range of colours also enabled me to associate it with some of those that Fortuny used in another Granada painting, Carmen Bastián. Without achieving the luminosity that can be observed in the latter, the fact is that the use of a very similar greyish colour can be discerned on the wall in the background of the composition.

With respect to the figurative anatomy of the two women, a first observation led me to think about the similarities between their faces and those in another emblematic production from this same period. I am referring to Carnival in Granada, also known as Life’s Contrasts (whereabouts unknown). The fact that the faces of some of the figures in the composition are hidden behind masks led me to establish a parallel with the said work, because in it one of the faces, due to its physical deformity, was suggestive of a mask.

This first link in the chain of connections led me to establish a concatenation of influences that would begin with Goya, visible and very much present in many of his compositions, starting with The Spanish Wedding, or in The Poets’Garden (whereabouts unknown), the most obvious examples in which one sees how indebted he was to the great genius from Aragon.

Marià Fortuny, Interior of the Church of San José, c. 1868; Francisco de Goya,

[Mujeres rezando], 1812. Biblioteca Digital Hispánica, Biblioteca Nacional.

The work I am discussing also partakes of this same visual culture and in it we find a lingering suggestion of these Goya-esque echoes. A second observable influence is the reflection of Japanese tradition, in this case underpinned by the memory of Fortuny as a collector. His collection included examples of oriental masks, visible in some of the photographs taken in his atelier in Rome, which as is well known was remarkable for the importance and the interest of the objects in it.

Moreover, as I have already said, the research done has enabled me to confirm the Granada hypothesis. I have managed to prove that the work was among the goods in the famous auction of the Fortuny atelier, held in the Hôtel Drouot in Paris. In the bottom right-hand corner, the stamp of the estate confirms the authenticity of the piece and also that it was one of the objects found in the painter’s studio after his death in 1874.

The composition appears, with epigraph number 78, in the inventory of the objects that were auctioned off on 27 April 1875, and it was acquired, for the sum of 850 francs, by the great American sugar tycoon William Hood Stewart (1820-1897).

Similarly, I have been able to confirm that the measurements of the work Two Beggar Women are the same as those that figure in the catalogue published for the auction, identified with number 127, entitled Beggar Women in the Doorway of a Church, in Granada.

Stewart a great collector of Fortuny

Stewart became one of the most reputed collectors of Fortuny, as he eventually owned more than 25 of his works. Apart from the number, what is most significant is that the collection included some of the painter’s most canonical works, like for example, one of the three versions of The Print Collector (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), one of the two versions of Arab Fantasia (The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore), one of the two versions of Masquerade (The Metropolitan Museum), The Cafe of the Swallows (The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore), The Court of the Alhambra (Gala-Dalí Foundation), The Choice of a Model (The National Gallery of Washington, Corcoran Collection), The Slaughterhouse at Portici (whereabouts unknown), Miss Del Castillo on her Deathbed, and The Prayer. Of these, the Museu Nacional conserves the last two. The first one was acquired in 1922 and the second, an unfinished watercolour, was acquired through popular subscription in 2013, thanks to the initiative of the Friends of the Museum Foundation.

At an unknown date, however, Stewart must have sold or given away the painting Two Beggar Women, because I have been unable to find any trace of it in the catalogue of the collection, published in 1898 for its public sale.

Curiously, in 1914 the work, which was owned by a French collector whose identity I have been unable to confirm, appeared once more in a collective auction that was held in the Hôtel Drouot. As it was not sold for the price set by the owner, after being repurchased it was returned to the seller.

Two Beggar Women in the context of the museum’s collection

Due to the importance of the collection of works by Fortuny conserved by the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, the acquisition of this painting, done by the artist in Granada, reinforces the place it occupies with regard to knowledge and study of the work of one of the most international Catalan painters. Likewise, its incorporation helps to strengthen the effectiveness of the Modern Art Collection’s exhibitory narrative. A composition that transcends the circumstances of the time when it was made, it prefigures a sensibility that connects with the modern tradition and enables a dialogue to be established with the work of Isidre Nonell, considered to have been one of the artists who contributed most to the emergence of the modern tradition and the gestation of a new visual paradigm.

Isidre Nonell, Gypsy Couple (1904), Poor Woman Praying (1894) and Blind beggar (1906). Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

Like Fortuny, Nonell also had a special liking for depicting subjects far removed from bourgeois taste, in which the figures were from the social groups who had been swept off the path of history. With their expressions, Nonell individualized the faces of wretchedness, poverty and marginalization and conferred upon them an ethical and artistic dignity that these figures had hitherto lacked. In this sense, apart from a very similar sensibility, the connection between both traditions, represented by each of these two great painters, is obvious. In Nonell however, unlike Fortuny, there was no lasting aftertaste of the folkloric and archetypal ideas that had marked painting in the nineteenth century.

Marià Fortuny, Cave of Gypsyes, The Corcoran Gallery of Art and Isidre Nonell, Qui caurà? (Who’ll fall?), 1906

Related links

«Non Finito». Fortuny and the paradox of the perfeccionist /1

Fortuny’s Carmen Bastián: problems with its reception and interpretation

Marià Fortuny: painting as the representation of a worldview

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats