Eduard Vallès and Elena Llorens

The Spanish Civil War was, without doubt, one of the bloodiest wars in the European history of the twentieth century and as such not only opened a deep wound in Spanish society but also left an indelible mark on the artistic production of the time, formally and thematically determining it.

Due to various historical circumstances, the collections of the Museu Nacional include an important collection of works carried out during the war in which it is worth highlighting a very relevant part in terms of quantity and quality from the Spanish Pavilion at the International Exposition of Paris in 1937, little known by the general public.

In 2014, on the occasion of the renovation of the permanent rooms of Modern Art, it was decided to complete the exhibition tour with a newly created space entitled “Art and Civil War”, in what was a clear declaration of intentions from the institution and which highlights a part, small but representative, of the artistic collection of this period.

Seven years later, from the Museu Nacional we have considered that this space could be enhanced at various levels: in terms of discourse, the number of works and the exhibition space, especially considering that one of the axes of the 2021 programme has revolved around the Civil War based on a series of exhibitions, artistic interventions and activities of a very diverse nature.

Thus, the renovation of the rooms dedicated to the art of the Civil War has meant, in the first place, allocating three more spaces, up to five rooms, which allows 43 different artists to be exhibited with a total of 108 works including painting, sculpture, drawing, photography, engraving and posters, in the line of combining diverse artistic registers beyond the hierarchies as in the rest of the Modern Art collection. Furthermore, it also allows visibility to be given to the paper money, the banknotes, issued during the Civil War that is preserved in the collection of the Numismatic Cabinet, and continues to count on cinema, once again with the collaboration of the Filmoteca de Catalunya.

Regarding the exhibition spaces, they respond, in general terms, to thematic groups defined by iconography, which largely monopolise scenes, characters and situations of war. As a relevant fact, it should be noted that half of the works had never been exhibited in the permanent rooms, which in itself indicates that we are facing a new and radical commitment to complete the permanent collection of Modern Art.

The bombings and the role of women during the way

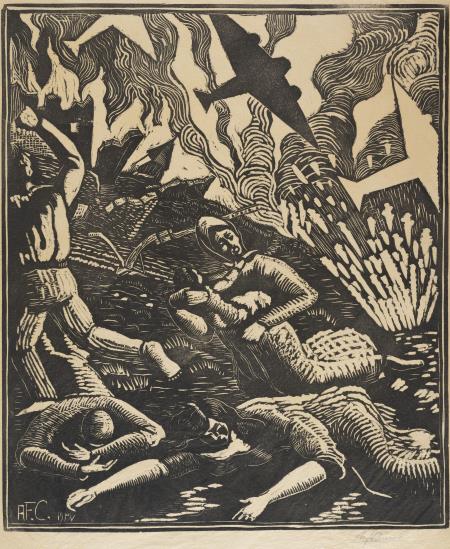

The tour begins with a space (Room 76) dedicated to the bombings and women in wartime where paintings of bombed neighbourhoods coexist, divisions of planes in the middle of bombing, and some images of great modernity. For example, a drawing by Enric Climent or an engraving by Andrés Fernández Cuervo, both of great chromatic economy, which show the horror of the civilian population fleeing under the threatening sight of black planes. This image is replicated in various works of the time precisely because of their hitherto unpublished character, the indiscriminate air attack on defenceless civilians, which was immediately captured by the artists.

Wall mural of the Pavilion of the Republic made by Josep Renau with the image of a militiawoman. Image. RMN; and J. Pons [?]. Lina Ódena, 1937.

Women artists occupy a space combined with representations of women as victims or heroines, in which the case of the famous militia women is worth highlighting. For the first time, two very unknown artists are exhibited, Juana Francisca Rubio and Àngela Nebot, with two works that participated in the Quarterly Exhibition of Plastic Arts of 1938. Both works are striking, and especially crude is the representation of a schoolteacher who had just been shot inside the classroom on Nebot’s canvas. The figure of the militiaman focuses on the iconography of a couple of works, the portrait of Lina Ódena, of an unknown J. Pons, and the major canvas by Celso Lagar which has been deposited by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, which, above any formal consideration, has an undoubted historical and documentary value. It should be remembered that Lina Ódena was a young communist activist who enlisted as a volunteer in the militia and preferred to take her own life before falling into the hands of the insurgents.

In this dialectic victims-heroes (Lina Òdena has this double condition) it is worth highlighting the large-sized Executions at Badajoz bull ring by Martí Bas and the life-size sculptural portrait that Josep Viladomat did of the Madrid militiaman Ramón Vía, better known as El Madriles. Both can be found in Room 77, in dialogue with the republican posters present in this space since the renovation in 2014, signed by some of the most famous names in the history of war posters such as Josep Renau, Carles Fontserè or Martí Bas himself. Soon, these republican posters would have their replication with the presence of posters of the insurgent side, which would allow the propagandistic dialectic that took place at that historical moment to be reproduced.

The Pavilion of the Republic in Paris. Armies and evacuations

The next space is entirely dedicated to the Pavilion of the Republic (Room 79), where the didactic element is combined with that of heritage: photographs of the Pavilion of the Republic are projected, and in some of which you can see in context works of the Museum’s collection that were present, as is the case of the sculpture Bather, by Francisco Pérez Mateo, which along with Montserrat by Juli González and some sculptures by Picasso, were exhibited outside the building designed by Josep Lluís Sert and Luis Lacasa; or the Bombed neighbourhood by Eduardo Vicente and the Espigolaires by Miguel Prieto.

Exterior of the Republic Pavilion. Access ramp to the first floor, and the sculpture Bather by Francisco Pérez Mateo. Image: Centro Documental de la Memoria Histórica ; Francisco Pérez Mateo, Bather, circa 1935

Although it does not appear in any of the period photographs that are preserved, the painting Allegory of the execution of Federico García Lorca, by Fernando Briones, is testimony to the homage that the Government of the Republic explicitly paid to the poet shot in the magnificent propaganda showcase that was the Pavilion. Despite having this specific space, there are other works from the pavilion spread across the five rooms, almost forty including sculptures, paintings, drawings and engravings. Of the latter, the series of satirical engravings by Francisco Mateos and Ramón Puyol stand out, being of great expressive force and which allow suggestive sociological interpretations of the different agents of the war.

The fourth space (Room 78) is dedicated to one of the most common iconographies in any war, the soldiers, and the army. With a language close to social realism, in some cases even Mexican muralism, paintings of soldiers resting or in the trenches are exhibited, which in the room appear confronted, deliberately, with paintings that reveal the drama of the mass evacuations of the civilian population. Notable among these are Evacuation by Helios Gómez and the canvas Captives by Antoni Costa; the latter, it should be said, brings to light an iconography much less exploited by the plastic arts: prisoners of war (in this case, from the insurgent ranks).

Helios Gómez, Evacuation, 1937; i Antoni Costa, Barcelona, Captives, circa 1937

Photojournalism and cinema in wartime

The last space (Room 80) is dedicated to photography in its variant of photojournalism, with emblematic snapshots by names such as Agustí Centelles or Antoni Campañà, whose photographs are on display for the first time in the Museum’s permanent collection, specifically the Fuseller (The Rifleman), recently deposited by the Campañà family, and six photographs loaned by the family dating from July 1936, when the revolution broke out in Barcelona and, among other things, the graves of the convent of Les Saleses were desecrated in Passeig de Sant Joan. In contrast to these images, the Museum presents a drawing by Pere Pruna, recently acquired, which represents a militiawoman contemplating the corpse of one of these nuns.

Several films of the time are screened in an adjoining space, including Le martyre de la Catalogne (Catalonia martyr), by Laya Films, the film producer from the Comissariat de Propaganda de la Generalitat de Catalunya, (Commissariat of Propaganda of the Generalitat de Catalunya), which shows the devastating effects of the bombings on the civilian population, especially in Barcelona and Lleida. A fragment of a film of the Movimiento Revolucionario (CNT-FAI) is also projected with images that correspond to the same episode of desecration of the graves of the convent of Les Saleses. The visual game between drawings, photographs and cinema is part of a museographic approach that allows dialogues and interactions to be established between the different artistic registers of the rooms.

Pere Pruna, Encounter of a militiawoman with death, circa 1936-1939; and Antoni Campañà, Untitled [Exhibition of the mummies of the nuns, convent of the Salesians], 1936. Antoni Campañà family deposit

The exhibition design has been the work of Anna Alcubierre, who has perfectly maintained the balance between the museographic criteria imposed by the permanent collection and various new elements that help to enhance the atmosphere of the exhibition space. From now on, these rooms will undoubtedly be a benchmark space for art produced during the Spanish Civil War, to the extent that they provide a look at the war in all its complexity and highlight a significant number of works from the collection of the Museu Nacional, half of which had never been exhibited in the permanent collection.

Related links

Civil War, art, conflict and memory

The endless war. Antoni Campañà

Antoni Campañà. The tensions of a gaze (1906-1989) [Online exhibition]

Elena Llorens

and

Art modern i contemporani