Francesc Quílez

In the course of the nineteenth century, the traditional artist’s workplace was transformed into an interesting motif for the artistic practice of the period, acquiring a scenographic dimension that had hitherto been unexplored. The depiction of the workshop had in fact already been featured in some of the most outstanding creative episodes in the history of Western painting.

A paradigmatic case: Velázquez’s Las Meninas

To give just one example, Las Meninas by Velázquez – a work framed, among other aspects, in the context of the vindication of the nobility or dignity of painting – made the workshop of the great master from Seville one of the most important aspects of the composition and laid the foundations for the success of a theme that, over the years, became a recurring visual resource.

In this respect, the enigma of Las Meninas, the subject of many different interpretative readings, took shape in the expression of a painter who, with his frozen pose, took an ambivalent attitude. On the one hand, his engrossed gaze seemed to evoke the intellectual nature of the creative act, what Italian treatise writers, since the Renaissance, had defined as the idea mentale. On the other hand, despite this wish to see himself mirrored in the model of the liberal arts, Velázquez made the mechanical nature of his profession visible, since with his firm, determined and proud pose, he held the implements that allowed him to transform the idea and turn it into a material form.

The nineteenth century: the interest shifts from the exterior to the interior

In the nineteenth century painting developed a great liking for transforming the workshop into a recurring thematic motif. It is obvious that this view of his own world, almost as if it were an onanistic exercise, was indicative of the artist’s increased self-esteem. The Renaissance treatise writer and architect Leone Battista Alberti, in his treatise De Pictura (1435), had formulated a metaphor according to which the painter, once he had opened the window, had to direct his gaze to what was outside in order to paint the “nature” that unfolded before his eyes, in order to thus observe reality in perspective, with subjective distance. This metaphor, however, was rendered obsolete, because the interest moved from the exterior to the interior.

With his simile, Alberti also highlighted the importance of the principle of natural imitation, the famous imitatio, for the ideas of humanism, as the point of reference that was to guide artists’ work. In reality, it was a very ambiguous formulation, given that for him imitation did not only have a naturalistic basis, consisting of seeing oneself mirrored in the beauty and perfection that nature could offer us, it also had a component of moral recognition of the ancients. Classical thinkers, in keeping with the model of restoration of the principle of authority that had presided over Renaissance thinking, were as exemplary as nature itself, if not more so.

The workshop, a hidden uninteresting place in the early modern period

This exercise in external projection, together with the artist’s low self-esteem and social recognition in the early modern period, would explain why the natural habitat of creators, their lair, did not arouse much interest as either an iconographical or a literary motif, given that only a few descriptions of this workplace have survived. And yet, as you might expect, these units of production, whose size varied according to the number of commissions or the master’s prestige – which allowed him to have a large number of assistants – occupied a central place in the system of creation in the Ancien Régime and they were decisive for maintaining the demand of a clientele throughout that historical period, whose behaviour also oscillated between expansion and contraction.

It is therefore undeniable that the time devoted to working, in times of constant, steady demand, must have made it necessary for artists to spend a lot of time in places that, generally speaking, must have been very simple, small and uncomfortable living spaces. These characteristics would be a partial explanation for a dynamic that tended to hide a place that was not particularly attractive. In line with this reasoning, making it visible was not a useful strategy in the struggle to dignify artistic activity and put it on a par with the noble status that other disciplines, such as poetry, did enjoy.

On this point, we must not forget that Leonardo de Vinci, an artist who could hardly be suspected of being carried away by literary caprice, was truly obsessed with declaring that painting could be the equal of poetry. Despite his interest in demonstrating the scientific nature of artistic practice, of being guided by the use of a scientific method, based on experience and the verification of empirical facts, the artist was indebted to a cultural context and a mental framework that determined his position in this confrontation between disciplines, and he ended up accepting the hegemony of poetry. In this humanist context, it is pertinent to recall the beautiful words of Leonardo himself, when, to point out the singular aspects of both arts, he vehemently stated: “Painting is mute poetry, and poetry is blind painting.”

Another explanation for concealing the workplace could also have been related to the social consideration of artistic practice, which was very low, if not non-existent. The lack of appreciation, of distinction, led to a lack of self-esteem in the artist, an inferiority complex that, apart from a few isolated cases, made any attempt at social expansion difficult. If he was considered a craftsman, a manual worker, and not a person capable of constructing narratives, stories, it was logical that the artist should have chosen to remain invisible, not to expose himself, not to exhibit his natural habitat, that place where he worked and spent much of his life.

In general terms, according to this idea, the workshop, through an effect of osmosis, was forced to remain eclipsed, since it was merely a physical extension of its owner, a place without magic, dignity, or social appreciation. It had the same prosaic value, and caused the same indifference, as any shop selling products manufactured by a craftsman, belonging to particular guild.

The artist’s workshop at the end of the nineteenth century

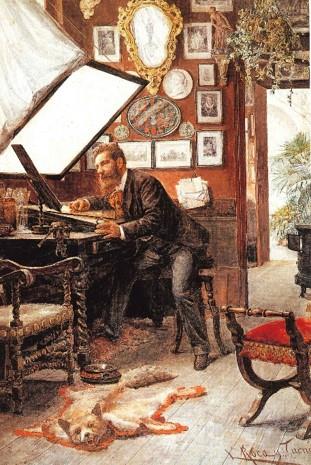

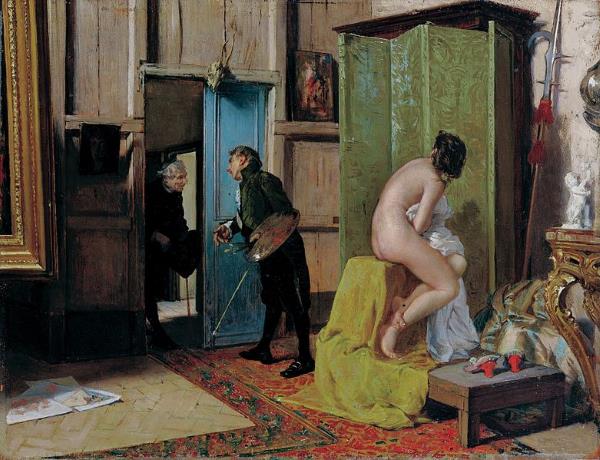

On the other hand, towards the end of the nineteenth century this situation was reversed and the opposite phenomenon arose. It was no longer necessary to go out in search of sources of inspiration, nor was it necessary to make nature the only aesthetic model. The artist’s own workshop offered a range of unsuspected creative possibilities and, what was even more satisfactory, it offered them without him having to make the effort to travel, enjoying the advantages of being able to work without forgoing the comfort and convenience of his own dwelling.

It is obvious therefore, that nineteenth-century creators stayed faithful to the tradition ushered in by Renaissance visual culture. The theme was frequently visited, so much so that it became a commonplace in the iconographical repertoire. However, the context was no longer the same; that old vindicatory motivation, so beloved in earlier periods, became an element that oscillated between banal, frivolous and unimportant treatment, typical of the painting of genre scenes, and the view of the workshop as a space with multiple uses and variables, among which the painting of anecdotal stories predominated.

The artist’s workshop in the Catalan context

In the Catalan historical context, this type of narrative scene became a phenomenon of the period and the representations were identified with the popular term ‘narrative painting’, a genre that, because of its pleasing characteristics, became very popular.

The theme dominated the Catalan painting scene in the latter decades of the nineteenth century, coinciding with the political period of the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. In this period, from 1874 to approximately 1890, the aforementioned depictions aroused the interest and even the enthusiasm of a clientele that saw in the images a model of the self-assertion of their own system of values. In actual fact, the presence of the workshop fulfilled a merely functional purpose, it performed a role of environmental support, a stage on which actions and anecdotes were represented, most of them costumbrista. The theatrical simile is valid as a means for understanding the extent to which painting was indebted to literature and how it used very similar criteria of mise-en-scène, with the presence of leading and supporting actors and with a narrative unity of space and time.

Related links

Scenes of creation: artists’ workshops / 2

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats