Francesc Quílez

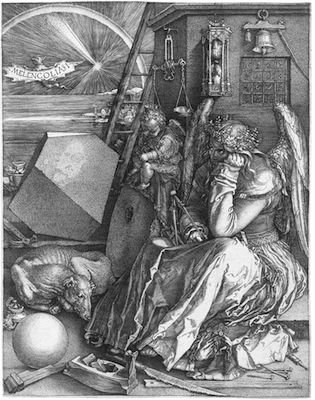

In a time of worry, such as we are currently experiencing, in which we are overcome with anxiety and on the horizon we see only the image of uncertainty and despair, humanity seeks answers, remedies to help it bear this heavy burden that weighs us down, limits us and prevents us from going forward.

Two decades into the 21st century we are facing an unexpected situation that has questioned man’s supposed unconditional ability and has shattered the foundations of an edifice, that of modernity, that we believed was resting on solid foundations. In reality, this epistemological construct, based on the supposed power of man, aided by limitless technological progress, has for some time being demonstrating its shortcomings and inadequacies.

Faith in progress, in mechanization, in the desire for power, to paraphrase Nietzsche, contained the seeds of its own self-destruction. As we have progressed, achieving material conquests, feeling ourselves capable of facing and overcoming any and all challenges, we have become spiritually impoverished and we have distanced ourselves from the principles and values that have contributed the most to comforting us in times when we discover our own fragility and that of the system to which we belong.

It has always been said, and rightly, that human thought never advances in linear terms, and that many of the reflections, observations, existential doubts and ideas are part of one cultural heritage, and that the same questions people asked in Antiquity are still valid today.

The work of art: from immanence to transcendence

In this respect, the work of art, understood as a form of reflection, of the projection of longings, hopes, desires, or as the reflection of the thinking of an age, a worldview or as a sensitive artefact that helps us discover unknown facets of our own human condition, is the best balm for curing the arrogance and the pride that generally characterizes us. From this perspective, art museums are rather more than simple containers of material objects placed in chronological order and grouped together according to stylistic affinities or similarities. Although this temporal sequence is important, we believe that it has rather an instrumental interest. When all is said and done, it is merely a guideline that anchors us with a factor, time, that is just another convention.

- A room of the Universal Exhibition of 1888, Palau de les Belles Arts.

- Museography of the Art and Archeology Museum at the Parc de la Ciutadella, 1915.

- Museo del Prado, Room of Queen Isabel II, c. 1899. Photo: Jean Laurent y Cie.

In my opinion, the essential thing about these artistic productions is that they help us to connect with the aspirations, the wishes, the intentions, or even, why not, the frustrations of historical subjects who, like us, also aspired to understand the complexity and the entirety of an unfathomable cosmos.

There were periods in which this uncertainty resulted in very disturbing and unusual spiritual responses, as they conferred magical, and even miraculous, properties on works of art; a supernatural power close to the idolatry of images. The icon became a magical object, a fetish, which was idolized because invoking it allowed one to work wonders, miraculous interventions that helped to overcome curses, hardships, illnesses, famine, epidemics (plague, cholera, etc.). Or the fear of a recurring ghost, that of millenarianism: with its apocalyptic trumpets, at the end of each millennium it announced the coming of the end of the world and threatened the worst misfortune for an unrepentant humanity, which would have to pay a high price for its sinful excesses.

- Jaume Cirera, Altarpiece of Saint Michael and Saint Peter (detail of the hell), 1432-1433, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

- Grup Vergós, Princess Eudoxia before the Tomb of Saint Stephen, 1495-1500, Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya.

The damned suffered all sorts of torments, hardships and misfortune. Confined in Hell, they were condemned to be devoured by the jaws of demons, evil creatures that in medieval times awakened the artistic imaginary, giving rise to a very rich and varied iconographic repertoire that through these images became a commonplace, in a place depicted visually which went on to take its place in the people’s imagination.

In fact, only poets – Dante for instance – or artists had been capable of materializing the fear and the anguish in the face of the unknown, everything that was ungraspable and generated unease. Despite their differences, artists had a therapeutic, healing effect, similar to that which many years later Freud would attempt to exert with his psychoanalytical theories. Not for nothing, unlike other mortals they had visited this dark, sinister place, inhabited by monstrous figures capable of transforming themselves and taking the most unbelievable forms. What was undoubtedly far more admirable was that, after going through this terrifying experience, they had managed to return and construct a narrative. Without doubt, this journey, apart from its poetic implications, was a truly heroic deed, an epic featuring a traveller who became a hero, since he had been able to go to a dangerous place and, what is more important, he had managed to survive, overcoming all kinds of difficulties and obstacles.

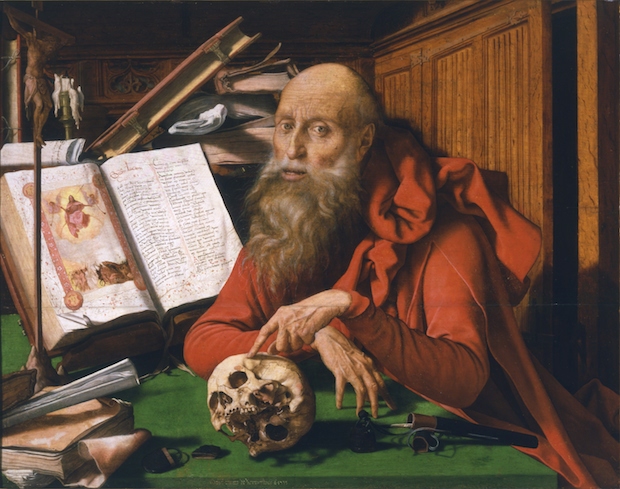

In the 17th century, artists exorcized these ghosts and demons that, as in the case of plague epidemics, caused a high death rate, with a type of work designed to allow people to atone for their feelings of guilt. The vanitas, as a genre aimed at fomenting reflection and spreading the Christian doctrine, came to occupy the place that these days is occupied by advertising campaigns promoted by the public institutions, aimed at raising society’s awareness about particular social problems.

Baroque painters used this theme for the purpose of spreading spiritual messages in which, in a Manichean way and at times using very dramatic visual effects, the superiority of spiritual over material values was stressed. At the same time, this iconographical repertoire also touched on the ephemeral nature of existence, the fragility of the human condition, the need to devote life to doing charitable deeds, to renounce flattery, material goods, or to become aware of the place occupied by mankind on the ladder of creation. Man was just one more creature that, like any other, had a finite nature, and, as a result, he ought to renounce fits of vanity (the reason for the name), all those pretensions to conceit, always remembering, like a kind of mantra, that he must internalize the words in the Bible: Vanitas vanitatis.

In this respect, the objects present in these compositions still have great magnetic power, they are hypnotic, because they have the potential to visually embody the message they wish to evoke. Without doubt, the skull is the most representative icon of this genre. Its presence shapes one of the great clichés and stereotypes, it is an indispensable element, which possesses great potential, as it continues to conserve all the properties for which it was created and used. It refers us to the idea of death, of sic transit gloria mundi.

It is a standard that is also a visual metaphor, the fate that awaits us all, regardless of our talent, our power, our glory, or whether we have devoted our life to action and not contemplation. It is, then, the object that makes us all equal, and which places us before the idea of the memento mori, due to the final journey that, one day or another, we will have to make.

- Juan de Valdés Leal, Finis gloriae mundi and In ictu oculi, 1672. Hospital de la Caridad de Sevilla. Photo: Wikipedia

- Antoni Fabrés, Vanitas (Sic transit gloria mundi), c. 1908. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The skull has another less obvious, more metaphorical significance, identical to the one we discover in some crucifixion scenes in which we see it at the foot of the cross. In both cases, the image constitutes a memory of the first man in the Bible, Adam, and how Christ’s sacrifice, his death and resurrection, redeems everybody.

All these examples, and others we could mention, highlight the need we still have to resort to works of art to acknowledge our strengths and weaknesses, to continue imagining, fantasizing, and to discover that many of the questions that we now ask ourselves were asked by our forebears. In reality, we are not so original nor so different from everyone who came before us, and who like us also felt the same worry, the same atavistic fears, about a future full of uncertainty.

Related links

- Vanitas in Google Arts & Culture

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats