Víctor Ramírez Tur

To talk about the simple desire, Andrés, we talk about Santos.

Those afternoons in the Church where you stay imprisoned, perplexed

and sucking the wounds from the side of Jesus,

or the arrows stuck in Sebastian’s naked body;

the wounds are like open mouths, and Genet understood

in his day and in our imagination we associate happiness

with that vision of Pain and Joy.

Pepe Espaliú, «Book of Andréss. A tale from yesterday»

Surely the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya is not the first place to where you would think to celebrate the month of LGTBI pride. However, the Department of Activities were not of the same opinion and proposed the possibility of carrying out four guided visits which were capable of mobilising queer narratives based on the main works from the museum’s collection. This text summarizes some derivations, some unexpected songs and a set of dissident affections that squatted the museum’s rooms on two Tuesdays and two Saturdays of June 2019.

Quite a challenge: how could we establish a dialogue with the museum’s works from an LGBTI viewpoint?

Obviously, the main question that guided the proposal from the outset was how to develop narratives linked to LGBTI activism from a set of pieces thought up, in their original context, for the representation of the contents of the Old and the New Testament or the daily life of the Catalan bourgeoisie. And even more so, how to do so by keeping an interest in these pieces and not losing their respect from easy positions of confrontation and sacrilege.

The answer, or rather, the answers, encouraged me to do a juggling act. We identified a couple of pieces or authors from which it was really possible to make queer narratives emerge without losing or altering their original intentions or their historical context. Ismael Smith and the representation of San Sebastián are the most obvious examples. We could have found some others, such as the portrait of the lesbian writer Colette. But this would have been insufficient and would have given the feeling that there really is a solid queer narrative in the museum. Hence the need for a second juggling exercise.

Where does the title Rebellious views come from?

The title of the visits and this text speaks of the possibility of cultivating “ Rebellious views”, a concept borrowed from the essay by Alberto Mira Rebellious views. Gays and lesbianas in the cinema (2008). In this text, the author explains that in his town, and as a young homosexual, he cultivated a rebelliousview with the cinema of Hollywood that allowed him to establish personal ties with fundamentally heterosexual narratives. Mira explicitly speaks of the existence of «currents of emotional and erotic sympathy that from the screen spoke to me even if they did it from heterosexual situations». And, based on this exercise, he invites all those non-normative and under-represented identities to the dominant narratives so as to install a crack through the cultivation of a deviated and unauthorized and undesirable taste; to establish a rebelliousview that allows one to make elements of personal experience dialogue with distant works at the beginning of the LGTBI experiences, in this case, the pieces of the collection of the Museu Nacional.

Now I had the title. The next exercise was how to develop this strategy in the Museu Nacional.

How to incorporate LGHTI narratives in the collections of the Museu Nacional

In December of 2018, I attended the University of Barcelona in the talk of researcher Élisabeth Lebovici, “All things queer, the impact of queer theory in contemporary art practices”, in which she discussed the intervention of Zoe Leonard at the Neue Galerie during the Documenta 9 of Kassel in 1992. The artist decided to empty part of the nineteenth-century collection of this institution to make dialogues of images of female genitals framed right up front in the foreground. In some of these images we saw the hands of those bodies stimulating the lips or the clitoris. Thus, in the months that the Documenta lasted, it was possible to install a rebellious views where academic paintings of submissive women talked with feminist empowerment. For Lebovici, this proposal made explicit out how «the museum is always half empty. Is always half empty of us».

Obviously at no stage did it occur to me to ask to empty half the museum. Neither did I see it necessary to do so because, what was indeed possible was to fill the museum of dialogues that, for at least four days, allowed a museum to be less empty of us.

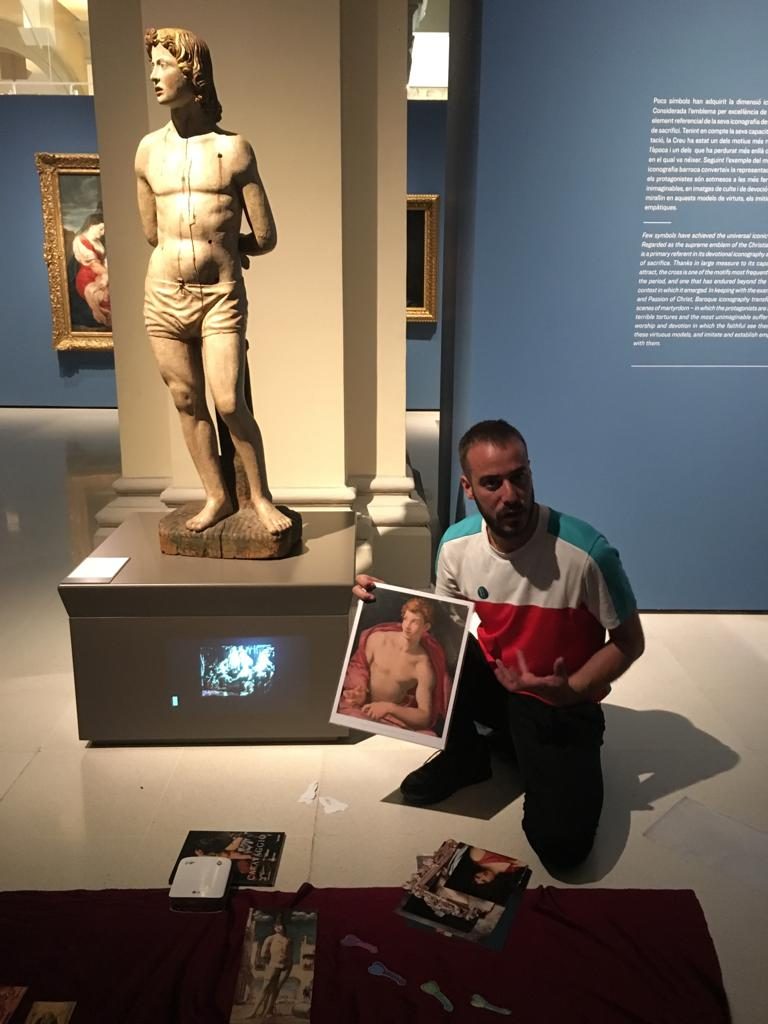

These dialogues took on two specific forms. On the one hand, I was accompanied by a small projector to help a set of visual dialogues to emerge on the pedestals, walls and tiles of the museum. As if it were a ghostly presence, homosexual, intersexual, lesbian or zero-positive experiences invaded the skin of the museum. On the other hand, given that we started from one of us, I decided to invite four friends who are developing projects linked to LGBTI experiences and activism.

Installation of Zoe Leonard at Documenta 9 of Kassel, 1992 (left). Projection at one of the pedestals of the museum where we recuperated other pieces produced by Ismael Smith (right).

Likorka Fey and Ismael Smith, a transgressive artist

If anyone embodied festive pride the most, it was Likorka Fey, drag artist, host and member of the Futuroa collective with whom they organized the Sarao Drag, an indispensable party of the city where the dance culture and drag race are recuperated. Likorka Fey presents this event that escapes from some more normative and neoliberal versions such as the famous RuPaul’s Drag Race, to welcome more fluid, more open and, above all, more critical, performance proposals for the genre. The drag artist was invited not only to help us to cultivate this rebellious view, but also to embody the spirit of Ismael Smith.

And what’s for sure, Smith’s trajectory is most explicitly installed in the queer narratives of the whole collection of the Museu Nacional. The artist has been a problematic figure for the historiography of Catalan art, since his work, unstable, grotesque, transgressive, ambiguous and mutant, never fitted in with a normative way either in the modernist circles, and much less in the Noucentistes. Surely for this reason, from the excellent collection that the museum has of the work of the artist, it has been decided to exhibit it in the rooms the Head of Don Quixote or Cervantes and the head of the Literary figure, two busts that not only represent extreme and extravagant characters, but also can be linked to content of sexual dissidence.

It is the case of this green head of a literary figure which it is believed to represent Aubrey Beardsley, described by Oscar Wilde in one of his texts as the man with silver-coloured skin and green hair.

These two artists are linked to the other reason why Smith’s work has been locked up in the cupboard until relatively recently: the link between artistic contents and a daily routine around the transgressing dandy, of the ambiguity of gender expression and experience -explicit in many cases- of homoerotic desires. Thus, on each one of the pedestals where the tops of the heads are placed, we project those drawings of Smith that are part of the museum’s collection, in which the Catalan bourgeoisie is transformed into sweet bejewelled men in heeled shoes, in women with strong and American jaws and in figures of clear sexual ambiguity.

We also recuperate the portable museum «Collection, cupboard and figure by Ismael Smith» that Equipo Palomar set up thanks to a grant from the Sala d’Art Jove in collaboration with the Museu Nacional. Of the multiple materials that we exhibit in this box-exhibition we highlight the facsimiles in the form of a postcard of those drawings of phallus and naked men in erection, that Smith had been producing throughout his career and that remained hidden in one of several archives of the main collector of his work, Enrique García-Herraiz. In fact, these drawings of clear homoerotic fascination for the masculine genitals had never been exhibited, not even in the major retrospective that the Museu Nacional dedicated to him in 2017.

Given that the chronicles of the context of Smith, like those of The Catalan people, present him as one of the first men who, at the beginning of the twentieth century, would enjoy putting on make-up, the presence in the rooms of Likorka Fey is undoubtedly the most appropriate invocation of the artist we could have. Following the visits of the month of June, the drag artist initiated the tour by interpreting in dialogue with sculptures such as Desolation –Josep Llimona- or Eva –Enric Clarasó-, the Salomé of Chayanne. Right in the middle of sculptures of women in rest or grieving, Likorka performed that constellation of “salomés” at the turn of the century from a homoerotic perspective from the version of Wilde and which Smith echoed, executing this sexuality version overflowing with one myth after the other.

Likorka Fey interpreting an acoustic version of the Salomé by Chayanne.

Based on the engraving of Smith belonging to the museum, Joseph in which he could represent his rejection of female sexuality through identification with Joseph, Likorka becomes a zarzuela singer to play “Ay, ba!” in the room around the Orientalism, linking the problematic exotic perspectives of the nineteenth century with the current debates around cultural appropriationism.

Likorka Fey and the representation of Saint Sebastian

As if he were Fregoli, Likorka takes on another identity throughout the visit, and embodies the little angel that often accompanies Sant Sebastián close to his ear, making reference to the ability of the saint to encourage the condemned Christians thanks to this angelic presence. The artist sings to us in our ears to accompany a tour that connects the sculpture of Smith that this saint represents and that can currently be found at the Cerdanyola Art Museum with other pieces from the collection where this iconography appears , such as the Calvary; San Sebastián -Joan Mates-, the Altarpiece of San Jerónimo, San Martín and San Sebastián -Jaume Ferrer- and the sculptural San Sebastián by Andrea Bregno

If we decide to incorporate this sequence into the framework of these rebellious visits, it is to track how and at what moment the iconography of this saint is linked to homoerotic looks or sexual ambiguity. In this sense, the collection of the museum allows us to see how the imagery of that apostolic, undressed, and even sensual San Sebastián, has not always been a constant in the history of art. This is demonstrated by the pieces belonging to the international Gothic of Ferrer and Mates where the saint appears dressed according to the courteous or chivalrous fashion of the period, holding in his hand the attributes of his martyrdom – the arrows – and, therefore, showing himself closer to his triumph over death.

If we move towards the Renaissance block of the collection, we will observe in Italy the tendencies in the representation of the same iconography and for the same period they already acquired other solutions. This is the case of the sculpture of Bregno, in which the saint is already naked, he shows himself to be young and Apollonian with blonde curly hair and without any pathetic symbol of suffering due to martyrdom. This piece serves us to display an iconographic constellation and observe, essentially, at the end of the 15th century and throughout the 16th a group of Italian artists such as Antonello da Messina and, above all, Perugino and Bronzino, fixed a iconographic typology of the saint that transforms him into a kind of Christian Apollo, as an excuse for artistic revival in the representation of the anatomy and of a sensual figure and ambiguous sex. As it has been pointed out more explicitly in relation to San Sebastián de Bronzino in 1533, this iconographic commitment would also filter possible contents or homoerotic approaches. Based on this premise, the saint would serve to open up two new paths to these rebellious visits.

Displaying a constellation of images based around the iconography of Saint Sebastian.

First of all, the ambiguity in the sexual or gender definition of the saint that was installed above all in the 16th-century plastic arts – we are thinking, for example, in Giorgione’s work – and from the nineteenth century on, it links with another of the best known iconographies of the androgyny: the angels.

Víctor Ramírez Tur