Eduard Vallès

It is by now wholly unnecessary to insist on Picasso’s very close ties with Barcelona, but there are a few episodes unknown to the majority, or which at the very least have hardly ever been mentioned. This is the case with the “poster” that Picasso made for the festivities of La Mercè in 1902, and we think this is a good time to talk about it here, coinciding as it does with the festivity of the patron saint of Barcelona.

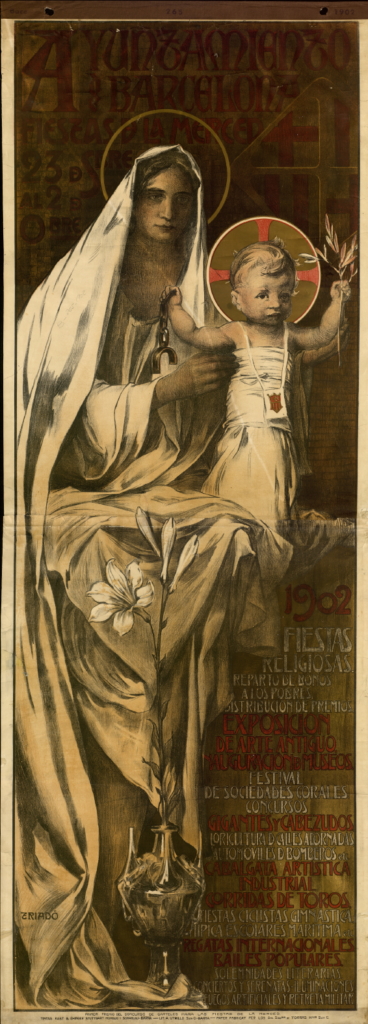

We have placed the word poster in inverted commas because in actual fact Picasso did not make a poster, nor did he enter a competition held for that reason (as far as we know). The end result, though, is that he did a drawing which, unofficially at least, could be granted this honour. In actual fact, that year the official poster was made by the artist Josep Triadó, well known for his symbolist work and his ex-libris, who won the competition with a work that was absolutely nothing like Picasso’s.

Triadó prevailed over other candidates, such as Xavier Nogués or Adrià Gual, with a vertically structured poster on a strictly religious theme, with the image of the Virgin Mary with the Child. We have to bear in mind that in 1902 the Festivities of La Mercè coincided with the well-known Exhibition of Antique Artin Barcelona, of religious art basically, which in fact opened on 25 September and was announced as one of the major activities to be held, as Triadó’s poster in fact mentioned.

The history of Picasso’s “poster” for La Mercè stems from his work for the newspaper El Liberal; one of the people who wrote in it was the art and theatre critic Carles Junyer Vidal, whose brother, the painter Sebastià Junyer Vidal, would later be a great friend of Picasso’s. Picasso had to return to Barcelona at the beginning of 1902 after a complicated 1901, with ups – an exhibition at the Galerie Vollard in Paris – and downs – the suicide of his friend Casagemas. We are just at the beginning of the Blue Period and Picasso’s career had not yet taken off, or it did not do so in the way he was hoping it would, the reason why he returned to Barcelona. In 1902 he worked regularly as an illustrator for the newspaper El Liberal, which was published in different cities but had a Barcelona edition, based in Carrer Nou de la Rambla, a few metres from Picasso’s workshop. Picasso contributed to it, doing all sorts of illustrations, and he even did copies of works by Puvis de Chavannes, Carrière and Rodin, which would be used to illustrate an article by Carles Junyer Vidal (El Liberal, 10 August 1903). Picasso also made various sketches for a planned poster for the newspaper, now in the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. This work, clearly done to allow him to subsist, was made in parallel to the high point of the Blue Period, eminently Barcelonan.

A historic celebration, 1902

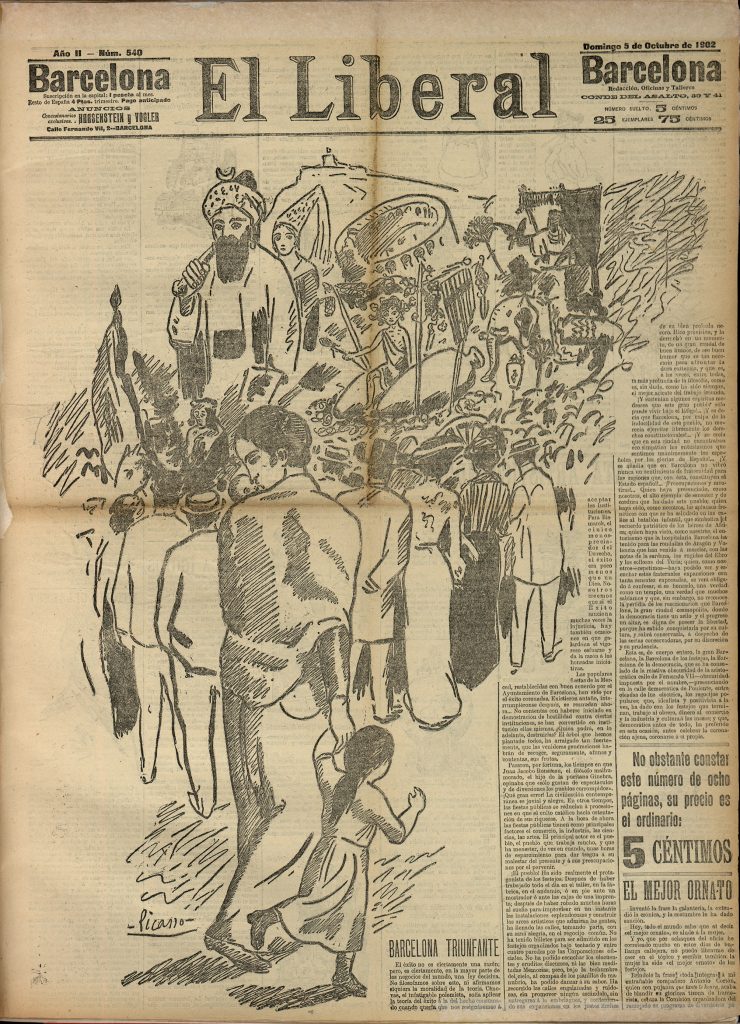

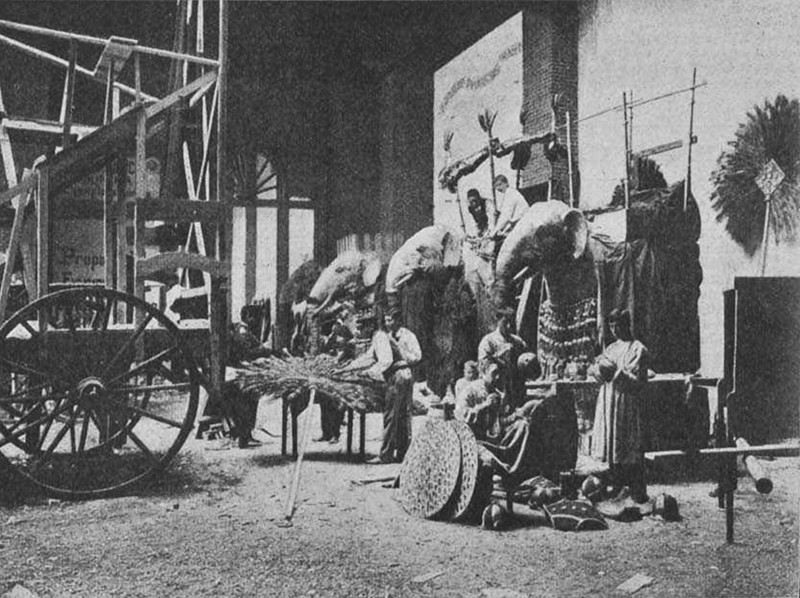

On 5 October 1902 Picasso illustrated the front page of the Barcelona edition of El Liberal, a front page that depicted the celebration of that year’s Festivity of La Mercè, which was particularly important. In fact, although the festivities had been celebrated since 1871, in 1902 the celebrations were given a completely new look, with the procession of giants and bigheads, or sardana dancing, among other novelties. This drawing is important in itself, but above all because it left a testimony of some of the elements of this renewed festivity. If you look at some photographs of that year’s festivities, some images can be identified that Picasso must have been able to see with his own eyes. For example, one of the giants that paraded is wearing a turban on its head crowned with a crescent moon, just as it appeared in Picasso’s drawing.

In the drawing some mechanical elephants can also be seen carrying a float on their backs, which could be the same ones in a fabulous photograph in L’Esquella de la Torratxa reproduced in a complete reportage about the festivities of that year, 1902, made by the weekly publication La Mira.

In short, it is an illustration Picasso was asked to do to accompany an article praising that year’s festivities, which had begun on 23 September. The editorial text appeared on the front page, entitled Barcelona triunfante (Barcelona Triumphant) and although the writer’s name is not mentioned, it was most probably by Carles Junyer Vidal. The original drawing is now lost, unlike others Picasso did that were published in the same newspaper.

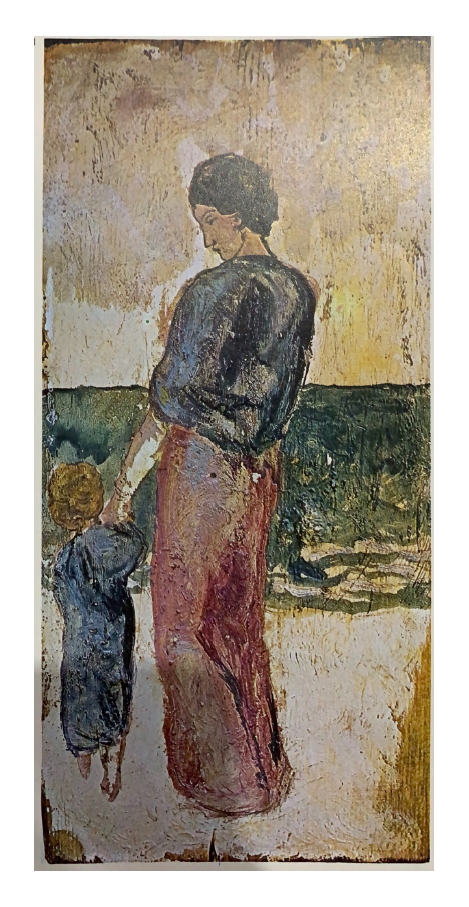

A blue motherhood

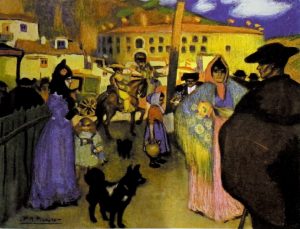

The clearest and most important figure in the drawing is without doubt the Virgin Mary with the Child, who are going to the celebrations; what could be more emblematic than a child with a joyful gesture (running with his hand raised) to symbolize the idea of a festivity. The mother and the child, in the foreground, are going to the different activities of the festivities, and they are in the midst of a crowd. In this respect Picasso focuses the composition not only on the child’s joy, but also on the people, after all it was a strictly popular celebration and Picasso was very well aware of that. But what the artist actually did was transfer to this drawing the iconography of his contemporary work, in which the images of mothers and children played a major part. They in fact appear from the very start of the Blue Period, when he did a few in Paris in the second half of 1901. Among the most significant ones are the images of syphilitic mothers accompanied by their children, which Picasso would have been able to see in the Saint-Lazare Prison Hospital. Back in Barcelona, in 1902 he continued with portraits of motherhood, some of them very similar compositionally to the one on the front page, with the child held by the hand as they walk, most of them frontal views, but some also seen from the back, as we can see in a painting in the Picasso Museum in Barcelona.

The La Mercè bullfight

There is one element in the drawing on the front page that is not usually recognized as belonging to the Festivities of La Mercè: a bullring, which Picasso places in the top half.

To understand this presence it has to be placed in context, as bullfighting was very popular at the turn of the century. Moreover, one must bear in mind that Picasso was a fan of bullfighting. We know that he went to bullfights in Barcelona and the La Mercè bullfight was important in the bullfighting season, as it was usually the last one. For Picasso and bullfighting fans like him, the La Mercè bullfight was unquestionably a celebration as important as any other.

In 1902 Barcelona had two working bullrings, the one in La Barceloneta (also known as El Torín) and Les Arenes. El Torín – long since demolished – is the one that Picasso most likely visited most often, seeing as it was the only one in Barcelona during his first five years in the city (1895-1900), and it is where he would have made most of his known bullfighting sketches and paintings, since he painted many of them in those five years. Les Arenes – now a shopping centre that has only maintained the original façade – was inaugurated in June 1900, while Picasso was in Barcelona, and he very probably also went to a bullfight there. Although the bullring in Picasso’s drawing is heavily sketched, he most likely got his inspiration in Les Arenes. The reason is that some horseshoe-shaped doors can be seen in it, and those in El Torín were not like that, but they were like that in a neo-Mudéjar building such as Les Arenes, designed by the architect August Font i Carreras. In fact, to mark the inaugural bullfight held there, the bullfighter Antonio Montes dedicated a bull to the architect of the bullring, curiously the same one who also designed the Palace of Fine Arts, where the inaugural event of the Universal Exposition of Barcelona was held in 1888. It later became a Municipal Museum, the first place in Barcelona where Picasso exhibited one of his paintings, First Communion, in 1896.

Picasso. Entrance to the bullring. Barcelona, 1900. Toyama Prefectural Museum of Art & Design (left); image of the frieze of giants, executed by Picasso at the Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Barcelona. COAC Archive (right).

A map of Catalonia

Picasso did not forget to add an explicit reference to the geography of the city of Barcelona and, in the top part of the drawing, he sketched the outline of the mountain of Montjuïc. After identifying Barcelona, however, Picasso went further than what would be required of an illustration that had to be exclusively about Barcelona, and he surprised everybody with the final composition. If you look at it closely, he actually groups together all the elements that make up the drawing in such a way that the whole ends up forming a map of Catalonia. The intention is so obvious that Picasso pushed the composition to the limit, filling with scribbles —apparently surplus to requirements — the parts of the drawing that he needed to complete the map. If we look closely the scribbles are placed at the southernmost tip (approximately where the comarques of El Montsià and El Baix Ebre would be); halfway up on the left-hand side, where there is the salient of the comarca of El Segrià, and in the top right-hand corner, which would be occupied approximately by L’Alt and El Baix Empordà. Picasso evidently knew how important Barcelona was as the capital, but he was also aware that the activities he was depicting (sardanas, giants, etc.), were actually manifestations of Catalan culture. Indeed, when in the 1960s he was commissioned to decorate the Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Picasso again included some giants in it, on the central frieze that overlooks the Plaça de la Catedral in Barcelona.

It is obvious that those giants were a reminder of the young Picasso, aged just over 20, who was beginning to making a name for himself in the art world, doing illustrations “to pay the rent”, even of Barcelona’s Festa Major.

Art modern i contemporani