Francesc Quílez i Eduard Vallès

The banality of everyday life

The major iconographic groups linked to the human figure that provided the vehicle enabling Nonell to find artistic elevation are, basically, those that represent the margins of society. However, in truth, a considerable proportion of Nonell’s production depicts his nearest environment, the urban artisan classes.

In both painting and drawing, Nonell depicts reality through a scrupulous gaze at his surroundings, and his work is not so unlike that of other contemporary artists, particularly Ricard Canals, who was said to be his “Siamese twin brother”, which would explain the similarities between some of their creations. Nonell became one of the sharpest and most brilliant chroniclers of his time, often leaning towards caricature, exercising a gaze that is at once sceptical and sympathetic towards the protagonists of his works.

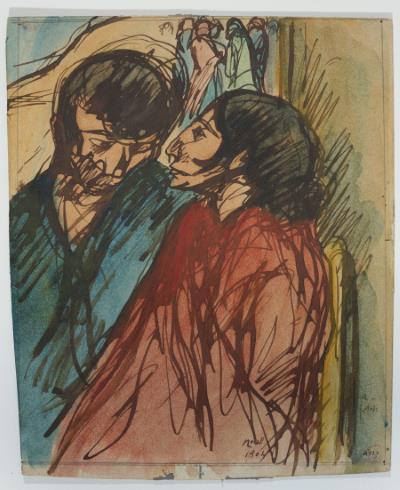

In his oil paintings, we can highlight particularly certain female figures from later periods when the artist has abandoned his earlier theme of gypsy women to produce compositions that feature a brighter colour palette. However, it is in drawing that Nonell finds the most appropriate language to depict everyday themes. His works on paper are mainly drawings made from life, and many were conceived as series, reaffirming the modernity of Nonell’s approach to art. Among the most outstanding are images of theatre audiences and scenes in church in which we see the congregation at prayer. However, generally speaking, the most brilliant are images of everyday life in the street, at the market, in the tavern or in public parks.

An overall view of these series – today widely scattered among different collections and museums – leads us to an interesting conclusion: that Nonell was an absolutely modern artist who repeated themes obsessively with the aim of experimenting, above all, with form and colour.

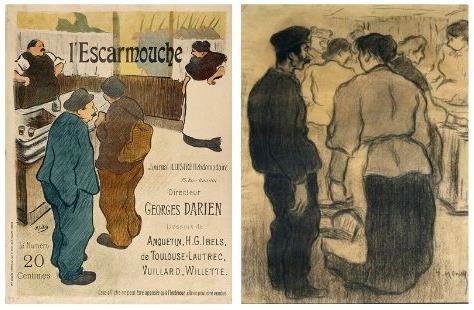

This focus on producing series of works confirms the importance of an artist who, through drawing, created an absolutely personal universe. The influence of the likes of Steinlen, Forain and so on is evident in some of these pieces, but Nonell went through different periods very quickly in his development. Just a few years after the period largely devoted to drawing, his production would begin to focus almost exclusively on painting, and works on paper would be relegated to second place. Nevertheless, Nonell would always retain the virtuosity and mastery that made him one of the great draughtsmen at around the turn of the twentieth century.

Rejecting ethnic stereotypes

Despite his industriousness and perseverance, Nonell never entirely won either critics or audiences over to his side. His choice of gypsy women as a theme was always resented by bourgeois audiences that could not understand his fascination with painting a figurative type so far from their own aesthetic tastes. At heart, his elevation of a theme of this nature and his rejection of the conventional method of representing the subject was seen as an act of defiance by a public still in thrall to the visual stereotypes applied to representations of gypsies throughout the nineteenth century. The objectified image of the gypsy woman was always and only acceptable if it responded to the clichés of the picturesque and the costumbrista “local colour” art with which they were habitually associated. But audiences could not accept unorthodox deviations that – as in the case of Nonell – sought to subvert these pre-existing models.

In fact, transforming this costumbrista tradition also entailed bringing to the fore an ethnic group – gypsies – who had always previously been consigned to the margins of history. From this perspective, the criticisms that Nonell received were always tainted by the class prejudices of a Barcelonan oligarchy that refused to countenance the possibility of altering the customs followed in painterly genres. Such a change would entail interpreting these series devoted to gypsy women not as depictions of a racial type, but as individual portraits of people who dared to occupy the place that had always been reserved for the social elites.

In this sense, Nonell’s poetic language is more demonstrative than narrative, and is characterised by great austerity, practically free from all superfluous, anecdotal motifs that might encourage aesthetic distraction or serve to provide a virtuous or artificial counterpoint to the composition. However, the absence of these auxiliary elements, setting the scene, does not mean that his painting is poor. Quite the contrary, in formal terms, the absence of these distractions increases the aesthetic power of the work, which concentrates on the figures represented. This has the effect of reaffirming Nonell’s determination to create a modern, innovative language, one based on purely aesthetic considerations and inspired by the desire to experiment with the interactions generated by a dialogue between form and colour, light and space. All this, without neglecting a construction process in which the artist creates monumental forms whose visual results resemble those characterised by sculptural work.

Satire and grotesque imagery

Irony is one of the traits that best define the modern artistic tradition. Through his or her creative skill, the artist demolishes our perceptions and breaks with social conventions. The ability to create caricatures of social realities is a useful tool in achieving these goals. Sarcasm, innuendo, self-parody and other approaches all help to subvert the established social order and to undermine the supposed resilience of such age-old institutions as the Church, the justice system and so on.

Nonell’s works feature veritable explosions of ironic distancing in which the artist gives full rein to his ability to laugh at himself. In this way, he demystifies the romantic aura that surrounds the figure of the genius and his or her supposed transformative power. Irony enables him to adopt a grotesque tone that links his work to that of other artists who, like Goya, Daumier and many others, share the same mocking gaze at the world around them. This is an attitude typical of people who observe the world with a rather cynical gaze, an existential scepticism that leads them to reject dogmatic beliefs. The rears of some of Nonell’s canvases, on which he painted caricaturesque self-portraits, reveal his disgust at the vain exhibitionism which often characterises artistic practice.

Isidre Nonell, The envious, 1909. El Conventet Collection, Barcelona; and Carles Casagemas, Old Couple, 1900-1901. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

In this satirical facet of his work, Nonell uses playful mechanisms to strip his professional activity of gravity and transcendence. In this way, he consciously places himself beyond the margins of the art system, undermining the importance of his own talent, his creative abilities. This playful approach also provides him with a mechanism for ironically distancing himself from the role conventionally assigned to artists, and from their social elevation. More than a position of humility or modesty, this stance can be interpreted as a response that affirms certain personal convictions which persuaded him to take an openly contradictory position. In this posture, we note two sides of the same determination. Firstly, on the front of his canvases are images of characters infused with great existential gravitas; and, secondly, on the rear, we are treated to an ironic expression of the artistic condition. This latter element was used as a support to conceal the artist’s face under the disguise of caricature, and to accentuate the tone of self-parody.

This text is an excerpt from the book recently published by the Museu Nacional about the artist Isidre Nonell Nonell. Visions from the margins.

Related links

Nonell. Visions from the margins

Nonell in context. Beauty from the margins

Nonell, between tradition and modernity: affinities and complicities /1

Eduard Vallès

and

Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats