Sara Guasteví

The access to the museums through Internet is a challenge that was achieved a long time ago, thanks to the consultation of automated catalogues, with increasingly more data and more precision. And their diffusion through the social media also. But as technical staff of the museums, when we visit other museums we cannot avoid searching for parallelisms, and if there are, we imagine what the dialogue would be between various pieces.

Music in thematic dialogues: beasts, clothing, painting

From the Museum of Music, we have for years dedicated all the Fridays of the first semester of the year to a digital project that allows us to know our collections, and sometimes those of other museums, through the social media, with a different vision to the one that the catalogues and the permanent exhibition provide us with. See the #Divendresbèsties, which includes all the instruments of the museum that have a relation with animals, either due to their materials, the shape, or because they have animals drawn on them, or the #DivenDress, a dialogue between pieces of clothing and musical instruments within a historic, social and musical context.

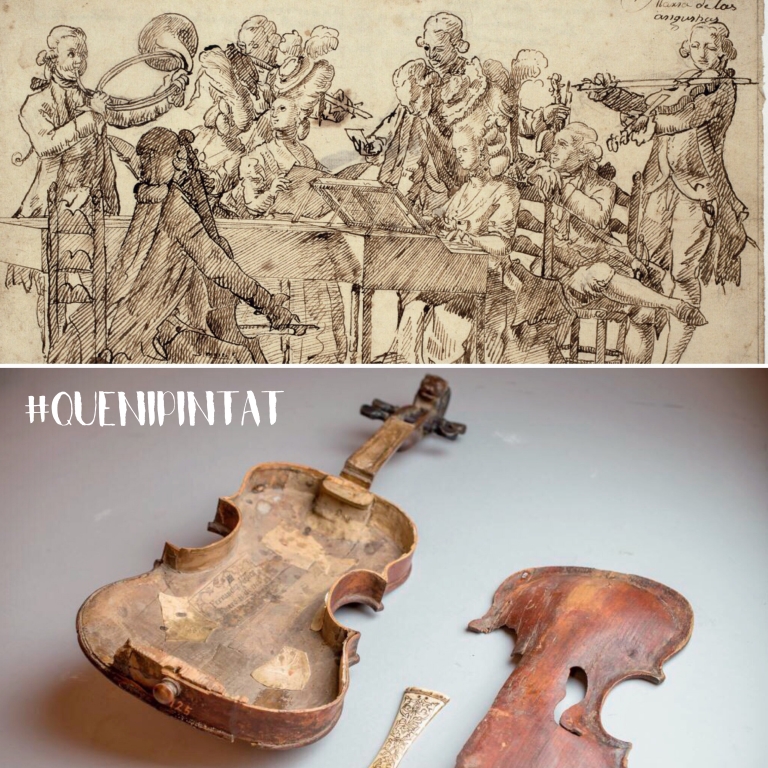

On a visit to the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya in 2015, entertaining ourselves by looking for instruments, when we still didn’t know that this research would be a project, and a talk by Jordi Ballester about musical iconography, they built what ended up being a dialogue between the two museums, under the title #quenipintat. The question that Ballester asked himself provided us with the basis of everything: “Why do musical instruments appear in the paintings?”.

Capturing the musical world before sound recording

Music is immaterial and the sound recordings are a later technology, except for some invention of barrel cylinders, which would not be developed until the end of the 19th century. Therefore, if the music was not live, it did not exist.

The fact that a painter might have made, precisely, an instrument, or a set of instruments or musicians to appear in a work, was the best way of insinuating what could be the “musical thread” of that particular scene, of that time and, moreover, it is one of the few ways we have, – the iconographic one or that someone had mentioned in writing, – to reach the musical world before sound recording.

Musical instruments in paintings: how have we worked on them?

However, here arrives the dialogue: the instruments that they painted, were they really like that? Through the project #quenipintat, we have looked for the confrontation of an iconographic selection from the collection of the Museu Nacional -26 works of art with texts by Jordi Ballester, from around 60 in which we have observed musical instruments, in a more or less notable way, showing in parallel real instruments from the collection of the Museum of Music of Barcelona, always aiming to achieve chronological coincidence or, on a few occasions, subsequent facsimile instruments.

Pau Gargallo, The Violinist, 1920 and violin, MDMB 851, Étienne Maire Clarà, 1895-1902

Once the idea had taken shape, we started a selection of instruments that coincided with the works of art, and both the collections department as well as the management department of the Museum of Music carried out a prior evaluation, because it was not always easy to discern exactly what the instrument represented was. The second filter and analysis of contents was already taking place with the professor and specialist in iconography, Jordi Ballester, who has offered us throughout the months, valuable texts that are the third important part of the project. Then we added the collection team and the networks of the Museu Nacional, with whom we finished defining the list (they provided us with more works that we did not know!) and we discussed how these publications could be.

Apart from renewing our view on what we believed we knew, with the main aim of observing the similarities and the differences, we have wanted to detect what impact an instrument can have on an art that, precisely, cannot be heard. In each case, we have tried to highlight a detail, a curiosity, an organological “unreality”, and a context.

As a curious example, we found a small buccin “being a dog”: in a poster, a harpsichord with the inverted box, or a cornamuse made by Pau Orriols, inspired by the painting with which he did a tandem.

The “que ni pintat” (not even painted), finally has consisted of words – diptychs – of the most instrument-based painting/object, which we have posted on various social media, Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, and that we have been adding in parallel in Pinterest. As for Twitter, considering the length of the texts, it is where perhaps the interpretation has proved to be more uncomfortable, but it has been where every week we asked our followers what music each tandem suggested to them, resulting in this playlist on the Spotify platform.

Through the texts proposed by Jordi Ballester we have rediscovered the bibliography on musical iconography of what we have in the library. And there has been an inverse process that has turned out to be even more interesting: every week, the team of the Museu Nacional has been incorporating in its catalogue the tags with the name of the instruments that we have mentioned, in such a way that now, if we search for instruments, but we do not remember the name of the author or the work, we will end up finding them!

And finally, we would like to pass on special thanks to Jordi Ballester, to Jaume Ayats, to the teams of collections of the two museums, and the support, information and accompaniment from the first day of the digital content team of the Museu Nacional, Conxa Rodà, Anna Ponce and Montse Gumà.

A good example of collaborative work between institutions.

What other thematic “tandems” would you like to explore from the collections of the museums?