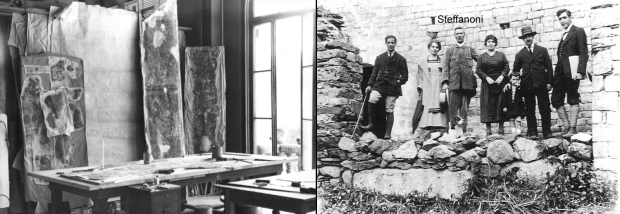

The museum’s wood restoration workshop and a photograph taken during the 1919-1923 detachment campaign, with Steffanoni in the middle. Photo: Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona. Photographer: unknown

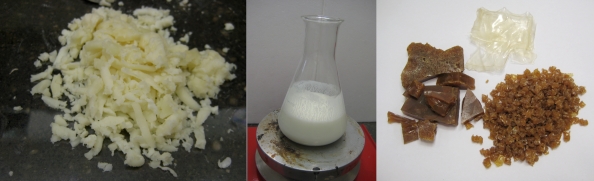

Cheese, milk, gelatin and flour could be some of the ingredients placed on the desks in Franco Steffanoni’s restoration workshop. We are not talking about a cook here, but a restorer who works with works of art –to be precise, with material patrimonial assets (for nobody can deny that culinary dishes are works of art too).

Steffanoni was the Italian restorer who, from 1919 to 1923, and aided by Cividini and Dalmati, detached some of the mural paintings from the Pyrenees that are now in the museum’s collection. Many papers have been written about this historic event, promoted by the Junta de Museus de Barcelona to put a stop to the spoliation and dispersal of Romanesque art, as had been the case in 1919 with Santa Maria del Mur. Here we shall merely focus on explaining how they did it and what materials they used.

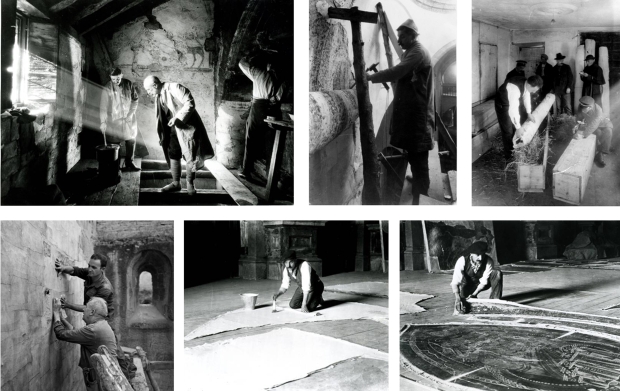

Different stages in the process of detaching, transporting and transferring mural paintings. Photo: Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona. Photographer: unknown

The history of detachments

The practice of detaching mural paintings began because people wanted to collect them, and it was already being used in the days of Vitruvius and Pliny. Then, detachment was done a stacco a masello, that is, by removing part of the wall on which the work had been painted. Throughout the course of history, the technique developed with the aim of making the part removed thinner and thinner, to thus be able to transfer it to a canvas, and hang the painting to decorate the walls of private collectors.

So it was that in 1730, in Cremona, Antonio Contri successfully experimented for the first time with the strappo technique, which is quite simple. It consists of sticking cotton cloths impregnated with a gelatin (rabbit-skin glue) over the painted surface, so that the tension created by the glue when it dries is strong enough to detach a fine film of carbonated paint, which sticks to the cloth. Later, in the middle of the nineteenth century in Bergamo, Giovanni Secco Suardo created a restoration school specializing in detachments and transfers. He used the strappo technique, and in order to stick the detached painting to a new canvas support he developed an adhesive made with a mixture of lime, cheese and milk. Steffanoni was a disciple of this school and he used very similar materials and methods in his work.

Formulas and ingredients

Let’s go back to the desks in Steffanoni, Cividini and Dalmati’s restoration workshop. There had to be large amounts of grated fresh cheese. Andreu Asturiol, a restorer working with Gudiol, who in the 1950s was still using the same transfer technique introduced by the Italians, recalls that they could easily spend an entire morning waiting for “all” the cheese that they had just bought to be grated, in order to do a job.

This cheese was boiled and the paste that was left was mixed with lime, in a proportion of one to three. Finally, fresh milk was added, so that this mixture – or mastich as they called it, nowadays we call it caseinate –would not dry too quickly and could be easily worked. Indeed, until the lleteries of Barcelona closed (milk shops with the cows in sheds at the back), the museum restorers used to take deliveries of milk from time to time. Over the years, however, these formulations have changed, and more industrial products have been introduced.

Cheese, milk and different types of gelatin (rabbit-skin glue and fish glue). All three ingredients were used in Secco Suardo’s original formula for transferring mural paintings

The analyses

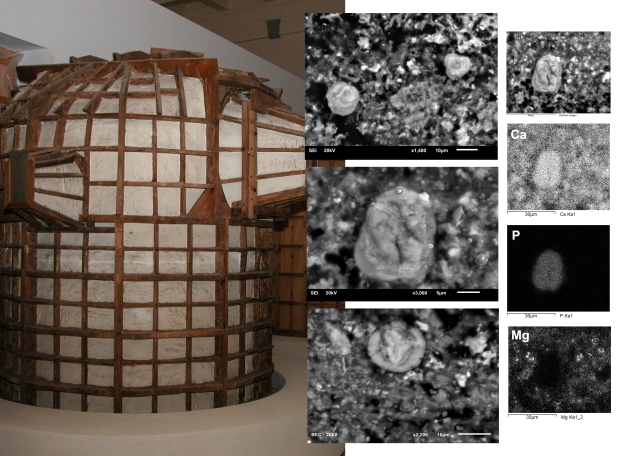

These ingredients are still found today in the internal layers of the mural paintings exhibited in the Romanesque rooms. As it is our responsibility to conserve them, we have to know how these materials change over time. This is achieved with physiochemical analyses. The results of the scientific tests that have enabled us to make progress in the knowledge of how these materials behave were presented at Science and Art V, held at the Reina Sofia in November 2014.

A bit of chemistry

How can a mixture of cheese and lime act as an adhesive? The main protein in milk is casein. Like all proteins, it is a chain made of bonded aminoacids and therefore a polymer. These chains can be combined with one another or with other chemical compounds, and weave networks. This gives casein adhesive properties. Furthermore, casein presents in the chain chemical reactive groups, acids and phosphates, which act as anchors or magnets with their surroundings. This characteristic of casein, present in both milk and cheese, is the reason why, as Cennino Cennini says, dairy products have been used as binders since ancient times.

The transfer technique consisted in sticking, with the prepared caseinate, two loosely woven cotton cloths onto the back of the fragments of mural painting that had been detached from the Pyrenees, rolled up and on the backs of mules. This gave them consistency and, as it was insoluble, the cloths with glue used during the detachment that were still attached to the front could be removed with hot water. Finally, in order to display the whole mural again, the fragments were stuck onto reproductions of the apse made with wooden stretchers, canvas and plaster preparations. Let’s not get ahead of ourselves: don’t suppose that they used the same casein adhesive in this last step. They prepared a different one, based this time on flour, which contains starch, another polymer, but constructed with units of glucose chained together. They made a sort of “béchamel” without milk, just water, to which they added gelatin.

The results

It is amazing that long before the industrial revolution in chemistry, restorers in the past were capable of inventing a system that was highly effective at the moment of application and, at the same time, surprisingly intelligent with regard to how it changed over the years. Although natural polymers such as casein or the cellulose in the cotton age and weaken, this effect is in part compensated for by the lime carbonation in the initial mixture, which hardens and at the same time acts as an adhesive. It’s simply brilliant! Now it is necessary to keep this system in conditions in which the humidity and temperature are controlled, to guarantee its maximum durability.

When you visit the museum’s Romanesque mural paintings, while you are enjoying the compositions of shapes and colours, and the stories they tell, from now on spare a brief thought for the layers beneath, which are a world unto themselves. They are full, for example, of microscopic nodules containing phosphorus and calcium, which are the footprints left by the casein, a reflection of its prime function in mammals’ milk: to envelop calcium phosphate nuclei to facilitate the transportation of minerals to new-born babies and to stop precipitates formation and blocking the mammary glands.

Detail of the back of an apse exhibited in the museum. Electron microscope images (magnification x 1000) of samples from Santa Maria de Taüll, Sant Climent de Taüll and Sant Romà de les Bons, in which the presence of nodules containing phosphorus (P) and calcium (Ca) is observed

In short, it is as if the early twentieth century restorers’ kitchen had managed to nourish paintings created 1,000 years earlier, in their new life after detachment, almost 100 years ago.

Restauració i Conservació Preventiva