Martí Casas

Ever since the world began, art has been a traveller. The news these days about auctions and the buying and selling of works of art may lead us to think that the importing and exporting of paintings, sculptures or jewellery is a relatively recent activity that emerged in the 19th century with the modern artist. In reality, however, for many centuries now we have been coming across works of art that have travelled a long way from the place where they were made, whether as purchases, plunder or diplomatic gifts. We have a good example of this in the Museu Nacional: since it was founded, a singular collection of sculptures has been conserved here, comprising 12 Renaissance marble reliefs that have many features in common and have shared the same destiny for almost 500 years.

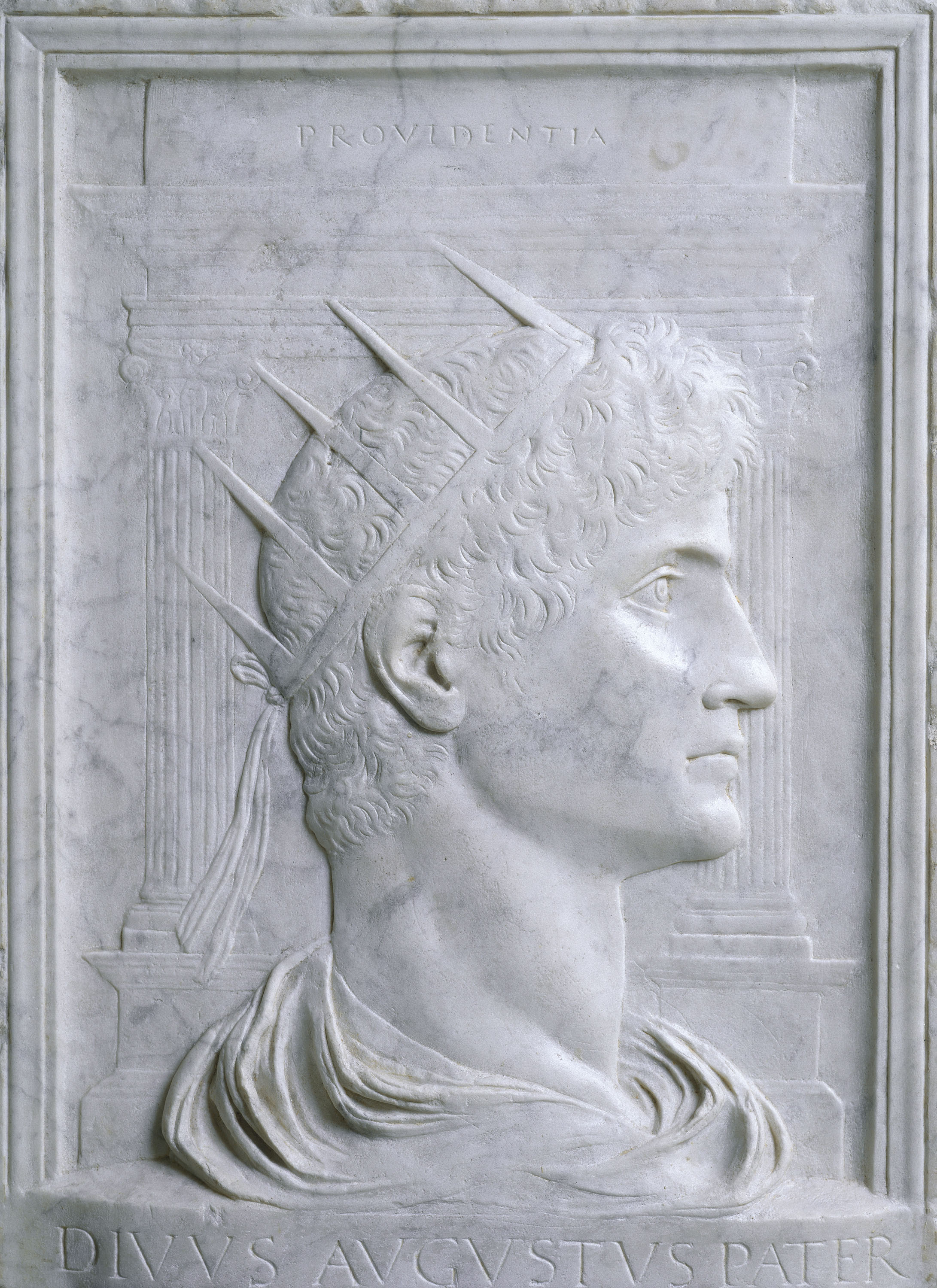

Pietro Urbano, Augustus, 1515-1525

Twelve singular sculptures

All but one of the reliefs are in the form of a tondo and display bust profile portraits of different male and female figures. Almost all of them are historical personalities of the Roman Empire, principally emperors. Both the style and the format of the reliefs are clearly inspired on the art of classical antiquity, the main point of reference and model of prestige for the artists of the Renaissance.

Alfonso Lombardi, Domitian, 1530-1533

The collection of sculptures is also striking for its quality, dating and provenance. Although the reliefs are the work of different artists, they are practically contemporaneous, dating from between the beginning and the middle of the 16th century, and at that time the quality and perfection of their carving could only be found in the workshops of central Italy. They are, therefore, clearly of Italian provenance. As none of the pieces is signed, attributing them to one or another artist has been a difficult task that has generated a great deal of debate among experts.

How and when did the 12 Italian reliefs arrive in Barcelona?

This is, almost certainly, the most interesting thing about their history. Thanks to documents that are conserved, we know that the pieces were purchased in Italy by the diplomat Miquel Mai (circa 1480 – 1546) during the years when the emperor Charles V sent him to Rome as the Spanish crown’s ambassador to the Holy See.

Niccolò Tribolo, Miquel Mai, 1528-1532

During his sojourn in Rome, from 1528 to 1533, Mai fitted in perfectly with the city’s cultural and artistic life. Following the example of his contemporaries, he built up a valuable library – which reached a total of 1,800 volumes and 400 manuscripts – and began collecting works of art made in the new style that was all the rage in Italy. It was also the style that best reflected Mai’s humanist and Erasmist ideas.

The ambassador had himself portrayed several times and in different formats in order to leave a record of the high status he had attained at the court of Charles V. Two of these portraits are conserved, virtually identical in their design, on a bronze medal and in one of the marble tondi that are now part of the Museu Nacional’s collection. In both of them Mai is portrayed with his true features and he appears dressed “in the Roman style” as a high-ranking dignitary in Antiquity. A declaration of intent if ever there was one.

Miquel Mai’s legacy

In 1533 Miquel Mai was appointed vice-chancellor of the Council of Aragon and returned to the peninsula. The library and the works of art purchased in Italy were brought to Barcelona, to his family home in Plaça de la Cucurulla. There, according to some authors, Mai had a Renaissance studiolo built in the style of the ones he had seen in Italy: a beautifully decorated studio where his artistic and bibliographical patrimony was conserved and exhibited, as though it were a treasure chamber.

The portrait of Miquel Mai and the rest of the marble reliefs that are now conserved in our museum must have been placed in this studiolo. The 12 pieces were deposited in the early 19th century in the antiquities museum of the Reial Acadèmia de Bones Lletres, the forerunner of the museum’s current collection.

Baccio Bandinelli, The Virtue of Prudence, 1525-1530

More sculptures imported from Italy

The journey made by Miquel Mai’s collection of marbles is not an isolated case. In fact, many Catalan personalities of the time bought works in Italy to bring them to the Principality. Why did they resort to importing them? The force of Gothic art in Catalonia meant that the new ideas of the Renaissance arrived here late, often superficially and watered down. Moreover, by around 1500 the local painting and sculpture schools had become outdated, and the principal artistic commissions were monopolized by foreign artists who turned out to be far more skilful and able in the use of the new artistic idioms coming from Italy. In the face of such an unpromising prospect, Catalan humanists who could afford to preferred to purchase higher-quality works directly in the place where the movement had originated.

Antonio del Pollaiuolo, Hadrian as Mars, 1485-1490

This is the case, for example, of the archdeacon Lluís Desplà i Homs, one of the great Catalan scholars of the 16th century and an important patron of the arts. Coming from the Archdeacon’s House aptly enough, the Museu Nacional conserves two delicate Renaissance marble reliefs that were almost certainly purchased by Desplà in Italy. The two pieces have reached us built into Gothic windows, in a singular mix of styles that was very habitual in 16th-century Catalan architecture.

Amics del Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya