Mireia Berenguer

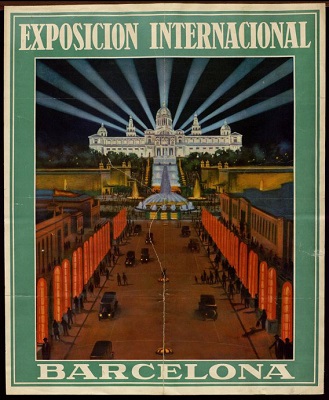

When you talk about the city of Barcelona graphically or draw its skyline, there are always a series of significant monuments and buildings in the city, such as the Sagrada Familia, the Agbar tower, the monument to Columbus or the triumphal arch, but there is also the Palau Nacional with its unmistakable beams of light.

Because these searchlights have become an authentic icon of Barcelona, an honorary testimony to the great anniversaries of the metropolis. Visible from anywhere in the city, they are turned on at night, from Thursday to Sunday, from May to September, and the rest of the months, from Friday to Sunday. Also on the big occasions, those days of major celebration in which some outstanding fact is commemorated or some special event is held, they shine majestically in the calm sky, because an indispensable condition is that the atmospheric circumstances allow so. This small symbol of the city has also inspired a logo, that of the Barcelona Trade Fair, and even a novel, Rayos by Miqui Otero.

The revaluation of the mountain of Montjuïc and the International Exposition of 1929

But let’s go back to the beginning of this history and it all started with the Montjuïc hill development project. This event has often been overshadowed by the 1929 Barcelona International Exposition, but the reality is that Ildefons Cerdà had already thought up, in 1872, an inclusive study of the hill in which he proposed its integral urban transformation. After many vicissitudes, this plan began to take shape around 1913, with the idea of organizing an Exhibition of Electrical Industries that, over the years, would end up becoming the major International Exposition of the 1929.

This project for the revaluation of the hill was conceived by none other than Josep Puig i Cadafalch as a whole artistic, cultural and symbolic ensemble and, although the urban planning works of the hill had already begun in 1917, the dictatorship of Primo de Rivera, in 1923, prevented the Catalan politician and architect from getting to build the main building of the whole project: the Palau Nacional. The work was finally commissioned to Pere Domènech, Enric Catà and Eugeni P. Cendoya, the former being the son of the brilliant modernist architect Lluís Domènech i Montaner and the latter two, his collaborator and disciple, respectively.

The major lighting plan for the International Exposition

One of the milestones of the designers of the exhibition was to try to provide the exhibition with the character of impressive grandeur, by producing a show of the highest aesthetic value and making the city boil with emotion and enthusiasm, attempting to achieve the fact that this decorative resource would offer a relatively new advance and well known in Barcelona, that was electricity.

One of the first and main projects of the exhibition was the major lighting plan, as its privileged location was the focal point of all the visitor’s eyes when the sun set. And notice how monumental it was, given that they then said that the water features and games of light of the exhibition alone, consumed 25% of the electricity of the whole city.

This ambitious staging, full of light, colour and water effects that stunned the senses, was designed by the young Barcelona engineer Carles Buïgas and managed to amaze everyone and attract comments from the far reaches of the earth, even though the Spaniards themselves did not believe that it was a locally produced invention. One journalist wrote: “At first, the endemic syndrome that characterizes the Spaniards resisted the assumption of the work of a compatriot and product of Hispanic manufacture. They thought of French, German or Yankee engineers. Especially in the latter.”

The project, however, was not easy. It was necessary to achieve a very intense lighting, given that an observer looking from the Plaza de España towards the exhibition had to sort through all kinds of water fountains, waterfalls and other luminous elements that would bring out all the necessary contrast to produce a vivid impression on the soul of the visitor, which was the goal that Buïgas had set when drawing up the plan.

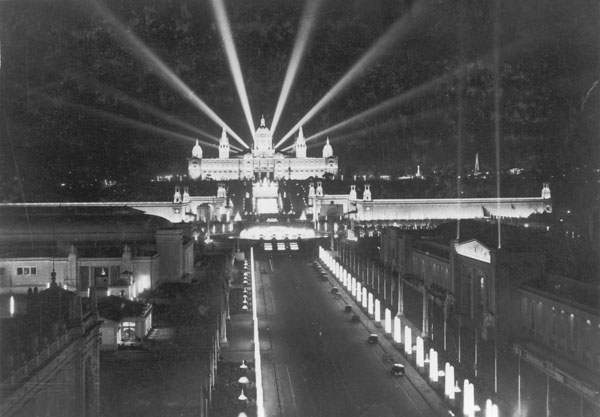

The rays of light of the Palau Nacional

In order to counteract this fact and for the illuminated silhouette of the Palau Nacional to stand out as much as possible, it was necessary to install a series of searchlights behind it, specifically in the perimeter gallery of the Sala Oval.

The press of the time narrated that “considerable efforts were made to keep these searchlights completely hidden, and to avoid not only the detestable glare, but also the unpleasant sight of the searchlights inconsistent with the finesse of the whole show.” Nine was the number chosen, as many letters as the city of Barcelona has and, at first, the lighting was planned for four colours: white, yellow, red and blue, as well as for all the binary combinations that these colours could form.

The result achieved did not disappoint anyone and comments and praise were printed in newspapers of all languages:

La Metropole, from Antwerp: “In the background, the searchlights thrown towards the sky halo the great dome of the Paulau Nacional. It looks as if we’ve been transported, magically, to the enchanted gardens of a dream palace.”

Fígaro, of Paris: “The pen is not apt enough to describe the miracle of Barcelona at night, seen from Tibidabo or from the flowery terraces of Montjuich. The electricity fairy, which has renewed the appearance of the world, has concentrated here her most unspeakable spells. A glory of gigantic fixed rays thrown into the sky, halo the Palau Nacional and make the stars pale, over this new Carthage.”

The make of searchlights was Sperry, designed by the American electrical engineer Elmer Sperry, inventor also, among others, of the gyro compass, which allowed sailors to follow with greater perfection the desired direction of the ships with a smaller movement of the rudder and of the so-called Lindbergh Light, a giant lighthouse that he gave to the city of Chicago and that is installed in its airport.

The Sperry devices had mirrors of about 91 cm in diameter and emitted a beam of light with an intensity of 450 million bulbs, with a scattering angle of about two degrees. They were the focus of concentration and, due to the fact that the light did not spread, they managed to illuminate at great distances. There were witnesses who claimed to have seen the halo from towns more than 100 kilometres from Barcelona. The fact is that the visibility of these light beams varies depending on the state of the sky. When it is filled with moisture, the range of the searchlights decreases, but also, when the atmosphere is absolutely clean, the visibility is also lower because there are no particles in the air capable of radiating the light emitted by the searchlights.

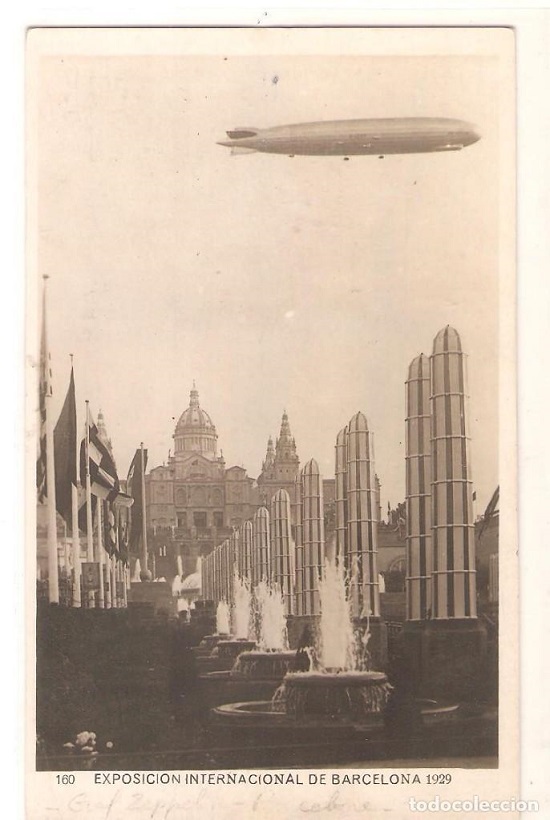

During the Exposition, Barcelona received the visit of the German Graff Zeppelin , the largest airship in history, 236 metres long, that flew over the city for a few hours on 23rd October, 1929. The arrival of this little monster was quite an event in the city, people went out on the balconies to greet it, and in the evening the searchlights of a German ship anchored in the harbour and the searchlights of the Palau Nacional followed it with their powerful rays.

Our fan-shaped searchlights illuminated the entire airship, along its entire length, as it circled the hill. The show, say those who were lucky enough to admire it, was truly fantastic because the Zeppelin, which turned silver in the searchlight, simulated a huge fish swimming over the blue sea of the sky. After passing through Barcelona, the Graff Zeppelin completed the first round-the-world tour of an airship.

The light beams during the Civil War

Once the exposition was over, during the Spanish Civil War, the searchlights of the Palace “were at the service of peace and culture,” as another reporter of the time wrote. More specifically, on the night of 2nd September, 1938, a squadron of five Italian “Savoia” planes attempted to fly over Barcelona, while being prevented by an anti-aircraft curtain of fire.

People, warned by the sirens, left their homes to hide themselves in the shelters, but the spectacle seen in the sky paralyzed more than one who was dazzled by that exciting display, completely forgetting of the imminent danger. The planes continued to fly parallel to the coast, to Cabrera de Mar, where they turned southwest. When they reached the vertical line of Besós, they were surprised by the beams of light from the Palau’s searchlights and a fighter from “La Gloriosa” started a fight with them. The fight was perfectly visible from the ground, watching as one of the three-engine engines of Mussolini’s fleet was trapped by machine-gun bursts, separated from the formation and lost height and speed. The plane fell into the sea, 4 kilometres from the coast, while the rest hurriedly dropped the bombs where they could, this time with luck in the sea, and fled to Palma de Mallorca.

Recovery of the splendour of the searchlights of the Palau Nacional

After the war, the rooms on the top floor of the Palace were completely unused due to damage to the roof, so we venture to believe that the searchlights could have been similarly damaged, because it was not until 1957 that they were reinstalled again. And in 1977 an attempt was made to bring the searchlight back to reflect the four bars of the Catalan flag with their gualda (a shade of yellow) and red colours, as some witnesses claimed to have seen years ago.

There has always been some controversy as to whether or not the searchlights really once projected the flag into the sky or not. Lluís Permanyer, in 2012, after researching this, unraveled the matter by locating a photograph of Zerkowitz that, although black and white, is accompanied by a legend that certifies it.

In 2018, they underwent a thorough restoration: they were taken down one by one, taken to a workshop, the casing was adapted, repainted and electronic rectifiers instead of electromagnetic ones were put on, adapting their technology to the commitment that the museum has had for some years now in terms of responsibility towards the environment.

Now, despite the difficult times we are going through, the searchlights of the Palace continue to tear the sky, imprinting on the black night the diadem of blue beams and giving clear and brilliant testimony to the hope of an entire city, which longs for the end of the pandemic.

Related links

The Palau Nacional. Architecture and memory

Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. The building

Col·leccions