The artist and curator Francesc Torres has spent the past two years delving into the stores of the museum to extract some censored, mutilated artworks, hidden for political reasons or destroyed for multiple reasons, and he has presented them in apparent disorder, in the exhibition The Entropic Box.The Museum of Lost Objects. This article has been produced based on extracted texts of the curator and his own experience.

Francesc Torres

Welcome to the Chaos of the House of Order. When the Museu Nacional called me to propose this project I thought that the best way of explaining the world is to always talk about something else, so I took the museum by the hands and like the film by Buster Keaton I went rolling down the stairs. The Entropic Box.The Museum of Lost Objects is the result of this imaginative stumbling block halfway between the curator and the work of art.

I haven’t done any of the works exhibited, I have chosen them as a curator would do to explain, propose and narrate a story. At the same time, I have used these same works as objets trouvées, as a raw material for producing a multimedia installation, interactive in the “old” way – there hasn’t been any art that isn’t interactive since Altamira, by the way– in a way that can’t be discerned in any moment, where one thing begins and where the other finishes.

I have tackled this project as a work of its own, exponentially greater than any other already done. I have examined the whole collection of the museum but I have narratively favoured works from the 19th and 20th century.

If the cities are the cemetery of their own past, the same can be said of the museums. Everything that is conserved is the fragmented reconstruction of the material history of the human species. It is of little importance that the pieces of the jigsaw are intact or fragmented given that they fulfil the same function. The museum preserves, narrates and explains, based on a massive decontextualisation of the objects of its collection (they are not where they were found), a fact that constitutes a contradiction of radical terms that is, precisely that which gives it the capacity for interpretation, situating it in a unique terrain between scientific and literary methodology, the former being what anchors and explains, and the latter which proposes, suggests and reveals.

Now yes, accompany me to the room.

The museum of lost objects

We are received by the accident state, a written-off Aston Martin DBS exemplifying a flat-out programmed accident, as with the demolition of the DNA of a whole building or the death of a living organism.

The appearance of Saint Francis of Assisi of Zurbarán, the carving of a Gothic Christ, Baroque reliquaries just as they are stored in the museum’s store rooms. The sacrifice that all accidents implicitly signify and the subsequent regrets, such as for example the recuperation of the remains, reach us through the objects that accompany the scene.

The Jewish problem

We find ourselves facing the Altarpiece of the Saint Johns of Bernat Martorell, from the 15th century. The particularity of this altarpiece in relation to the exhibition is multiple. On the one hand, the fragmentation is made evident: the central panel is conserved in the Museu Diocesà of Tarragona, the side panel in the Musée Rolin d’Autun in France, and a third panel was in an unknown location until very recently. So as to accentuate the relocation, I haven’t requested the missing panels from the museums that conserved them, I decided to put real-sized black and white photographic reproductions.

The empty space of the missing panel is occupied by a mirror which incorporates the spectator with the altarpiece, without spectators there’s no art, or dialogue, or play. The second particularity is that in the lower part of the altarpiece there appeared some Jewish characters with the faces scratched. This vandalism from the epoch has the historic counterpoint in the copy of the book The International Jew by Henry Ford, deeply admired by Hitler, one of the few characters mentioned in Mein Kampf.

Painting and fire

The first thing I saw during my first visit to the store-rooms of the museum, were the nine paintings by Sert, from the cathedral of Vic, burnt and damaged by the anarchist militia at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War (beautiful, by the way, after the torture).

These paintings dialogue with a work by Joan Miró, also burnt, but in this case by the artist, the deliberate result of a creative process. Modern art carried in the DNA of the unprecedented destruction of the 20th century, sometimes even a priori. You can’t deliberately burn a work just because it is, without bearing in mind the bombings of Dresden or Hiroshima in the subconscious archive we share.

The ravages of anger

The portrait of Napoleon’s brother was torn just after the French War, dated from 1893, is now restored. Given the good result of the restoration and the fact that on the front there are not many signs of the attack, I am exhibiting it accompanied by the little existing material that documents this history that had seemed interesting to me to exhibit, precisely to highlight one of the key functions of the museum: to rescue destroyed works and to return them to a reasonable state of conversation and exhibition.

Like the bust of Queen Isabel II, initially in the Teatre del Liceu of Barcelona and assaulted by the citizenship, taken out to the Rambles and thrown into the sea. It was found sometime later during the modernisation works of the port and conserved, since then, without being restored. In the strict sense, there isn’t any work of art anywhere in the world that is ‘perfect’ in the literal sense of the word, the important and interesting thing is the point in which a work is considered to be integral or stops being considered as such, a question open to debate.

Feminicide (for interposed art)

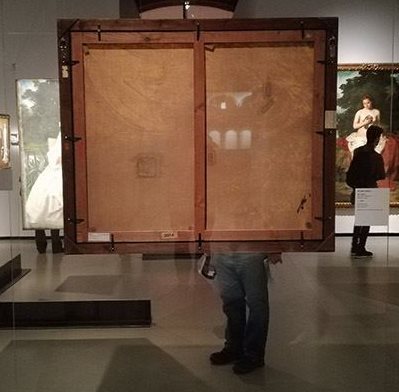

During the celebration of the Eucharistic Congress, in 1952, the first international event during the Franco regime, the Museu d’Art suffered a vandalistic attack which is still unresolved and one that continues to be unresolved. Someone entered the museum during the night and tore all the feminine nudes exhibited.

In the exhibition all the restored paintings are mounted on a thick plaque of methacrylate that allows you to see the extent of the damage on the back of the canvas.

The ones that aren’t restored I have hung in a traditional way on the wall, they are the most impressive. The counterpoint? A small reproduction of the Venus at her mirror by Velázquez in the National Gallery of London after having been attacked, at the beginning of the 20th century by the suffragette Mary Richardson. Finally, all of it becomes completed with a sequence of four photographs in a light box that shows Lucio Fontana in the moment in which he tore one of his works. An entire ideological spectrum of the attack on the figure of the woman from Catholic reactionarism to the progressive suffragism of the last century. If neither photography is objective by registering the present, how would the reconstruction be of the past based on fragmented papers and broken objects?

The scrambled house

There was a building from the 18th century, called Casa Serra, which no longer exists. It was located at number 22 of the Riera de Sant Joan, a street that also disappeared shortly after 1913, when Via Laietana was opened up to connect the Eixample with the port and to solve the problem of demographic congestion and the lack of hygiene in the area. Picasso painted the street from the balcony of his studio, which doesn’t exist either.

These mural paintings that show the “History of Rome” the work of Francesc Pla, “el Vigatà” (from Vic), decorated one of the rooms of the Casa Serra. Before the demolition they moved to the new family house in Bonanova. From that moment on, the panels went on a long trip: they went to the Barcelona City Council for the International Exposition of 1929, then they were deposited in the City History Museum, from where they moved to the Poble Espanyol to finally end up at the Museu d’Art de Catalunya in 1962. This busy trip ends with them landing upside down in the exhibition hall. The roof is on the floor and the walls are back to front. Or is it the viewers who are upside down? In Catalonia, as you know, everything is. It is a way of viewing the tombs of history and to directly emphasize the miracle of conservation of what remains after the accident (of a car? Ah, modernity!)

Put (the) doors on the street

The doors of Gaudí on the street! The Casa Batlló suffered many refurbishments before being declared National Artistic Historic Monument in 1969. The most important one being carried out in 1957 to accommodate the company Seguros Iberia. In a moment in which Gaudí was of little interest, it was when many of the doors and cupboards of the house were thrown on the street. Joan Ainaud de Lasarte, director of the Museus d’Art of Barcelona for almost forty years, saw them on the pavement when passing by in his car and called the City Council for them to collect them.

In 1986, they entered the collection of the Museu Nacional. This story is an example of the avatars that are subject to cultural and heritage sediments, as well as the importance of people with active instincts. At the same time it makes clear the enormous work of museums as guarantors of the cultural heritage of the society they serve. Where there are no museums, there is no history, no memory, no paradigm of excellence or citizen awareness. The problems that are produced in the museum are not systematic, they are problems caused by lack of intellectual clarity.

The king dressed in paint

There are, sometimes, indisputable traces of the spirit of a time and culture of a country precisely in what nobody wants to see. The Museu Nacional has a significant amount of portraits of King Alfons XIII highly varied in terms of quality and conservation. It seemed to me to be necessary to exhibit all of them without distinction and to relate them to the painting by Carmen Bastián de Fortuny, fragments of the pornographic films financed by the king and produced by the Count of Romanones and two terrible images of a series of postcards of the Annual Disaster of 1921, eight years before the International Exposition, and where around 13,000 Spanish soldiers died.

Ironies of history that a building with expiry date and not particularly well built, as is the National Palace, built to house the International Exposition of Barcelona in 1929, has become the guardian of the artistic heritage of Catalonia.

Republican moles

Hidden in full daylight, this was the intelligent strategy that was used after the Civil War to protect the art of the Republican period of the permanent collection, of the Museum of Modern Art, from fascism, located at the time in the Parc de la Ciutadella, and of the Museu de Arte de Catalunya, in the Palau Nacional. Instead of removing them to take them to a safe place, with the risk of being intercepted by the Franco authorities, they were hidden in a room in the building. In the room, some of the exhibited works cannot be seen as they were hidden in full daylight, a frustration sought as a recreation of the historical anecdote.

You can connect this episode with what recently happened with the museums and the Iraqi and Syrian archaeological remains at the hands of the fighters of the Islamic State. In the Middle East, just about nothing could be hidden, but fortune wanted that some sculptures to were reproductions of originals, which escaped the perception of barbarians.

Epilogue. The Museum of the demolitions

We have reached the end of the tour. “Every commodification is an oblivion,” wrote Adorno to Benjamin in 1940. If we take this reflection at face value it is obvious that any accumulation of objects, from the city to a museum, is a monument to historical amnesia. I say farewell to the exhibition with a collage of objects, construction and destruction tools, historical sediments of the museum and a counterfeit of a piece of mine from almost forty years ago: the city built with playing cards, an image that combines culture, fragility and chance.

Francesc Torres

Artist and curator

Related links

#CapsaEntròpica_concurs. Ended January 14, 2018. The photos presented at this Instagram contest can be seen at the hashtag #CapsaEntròpica_concurs.