Anna Carreras

Study of the restoration work prior to its admission to the museum

In an attempt to prolong the functional lives of works of art, the Catholic Church has often renewed their decoration, in order to reuse highly prized assets, joining them together artificially, updating them and adapting them to new tastes and liturgical uses. The case of the Christ and the cross from Capdella is a paradigmatic example of the reuse of materials and elements of varying provenance. This has been confirmed with the study of the two pieces in this group.

Back and front of the Christ and the cross before restoration. ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

The restoration of a medieval work of art is usually a complex process that consists not only of direct material action on the piece, but also involves making a wide-ranging and exhaustive study of it. Habitually, a study is made of the painting technique, the constructive system, and an assessment is made of the scope of any previous restoration work done on it. To obtain the most complete information, conservators-restorers need to consult different types of archive material that tell us about the history and the vicissitudes that the piece has suffered, and to conduct different inspections and scientific analyses such as radiography, infrared reflectography, optical microscopy, and analyses of materials to complement them, and they often confirm for us what can be sensed when the piece is observed analytically in detail. In this post I wish to focus on this previous point in which everything explained is a hypothesis, the product of deduction and the expert gaze.

Church of Sant Vicenç (La Torre de Capdella). Foto: Anna Carreras

The Christ from Capdella, originally in the church of Sant Vicenç in the village of La Torre de Capdella, entered the museum in 1932 as part of the collection of Lluís Plandiura, and it is now in the museum’s Romanesque art collection. The local council of Capdella was interested in having a copy of the Christ and the cross, and this led to the restoration and the detailed study of this singular piece.

Once the Christ had been detached from the cross, we proceeded to restore the cross. The first thing we noticed was the existing polychromy, consisting of yellow floral decoration on a green background. This can be seen on both the front and the back of the piece. On the back it can be seen that it has been repainted over another older layer with yellowy-orange geometric motifs inside black outlines. It is known that the Christs of that period were mounted on the bare wooden cross, with no layers of preparation or polychromy. These layers were applied later and this left an area without any polychromy in the middle of the cross and on the back of the Christ. This is why, when we saw this area without the first polychromy on our cross, we deduced that it must be a reused cross, and that it originally had a smaller Christ attached.

Virtual reconstruction of the first polychromy, on the back of the cross, with the unpainted area left by the Christ that had been nailed to it originally. Height of the unpainted area: 110 cm, height of the Christ from Capdella: 218 cm. Image: Anna Carreras / What was previously the front, now the back, with two superimposed polychromies. The second layer of polychromy that fills the unpainted area is visible. Photo: Anna Carreras

Later, the original Christ disappeared, the cross was turned round so that the back became the front and the present Christ from Capdella with the Romanesque polychromy was attached to it. The cross was repolychromed with a green background and yellow floral decoration. This work was done with the Christ attached to the cross and it also left an unpainted area.

Virtual image of the Christ with the Romanesque polychromy and the second polychromy on the cross. Image: Anna Carreras

Afterwards, and possibly as a result of aesthetic interest that fluctuated and changed over the years, some radical work was done on the Christ, which removed its Romanesque polychromy. The objective then was to change the position of the Christ’s body from a Christ in Majesty to a Suffering Christ. To achieve this the volume of the body was reduced by making it slenderer in some areas. When this work was done, the wood of the support was infested with xylophagous insects, as the galleries made by these insects can be seen, exposed and filled in some areas with the preparation layer of the following polychromy. The facial expression was also changed by placing the eyes higher up, making the outline of the face sharper and varying the position of the head thanks to the adhesion of a wooden graft to the back of the neck.

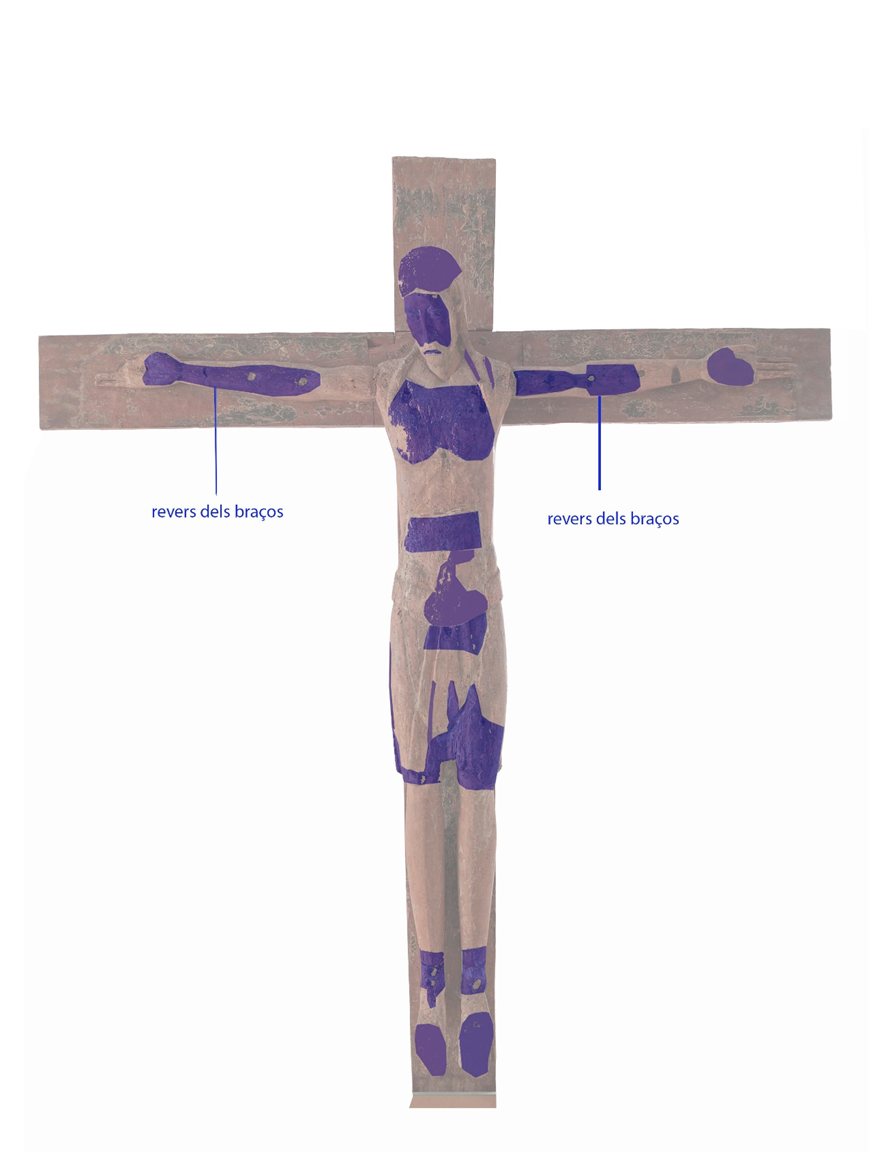

Mapping of the areas where the wooden support was removed, now without the Romanesque polychromy. Image: Anna Carreras

Details of some marks made by the tools used to reduce the support. Photo: Anna Carreras

Details of the galleries of xylophagous insects, exposed and in some cases filled with the layer of preparation, prior to the application of polychromy. Photo: Anna Carreras

Detail of the graft applied to the back of the neck. Photo: Anna Carreras

After that it was polychromed and the third polychromy was applied to the cross, apparently homogeneous and reddish in colour, as can be observed in the isolated traces that have survived, and as can be sensed in the photographs taken in the 1920s.

Photographs taken in the 1920s in which the Christ can be seen with the polychromy, in front of the door of the church of Sant Vicenç in Capdella. Photo: Arxiu Mas and Arxiu Diocesà de la Seu d’Urgell

Detail of the traces of the last red ochre polychromy on the cross. / Traces of red ochre polychromy on the cross that have been transferred to the back of the Christ’s right leg. Foto: Anna Carreras

Photograph of the Christ and the cross as part of the Plandiura Collection. The Christ is observed with no polychromy and the first two applications on the cross have survived, the state in which it entered the museum some years laterPhotograph from the Photographic Archive of Barcelona. 1920s. Photo: Arxiu Fotogràfic de Barcelona

At a later date, and supposedly in an attempt to recover the original Romanesque polychromies, the red was stripped from the cross, while the first and second polychromies were conserved, and the Christ’s only polychromy was removed. We should remember that the Christ no longer had the Romanesque polychromy, just a few odd traces of it remained, given that it had been removed at the time of the work that changed its volume and facial expression. And this is how the Christ is conserved today, with the support visible.

On the back, in the area between the shoulders, there is a niche that conserves a lipsanotheca with the remains of bones. It is a reliquary that is not original, coarsely made, and which was possibly open at different times.

Lipsanotheca with the remains of bones. ©Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya

To end, I would just like to mention the graft now visible to the naked eye and situated in the area of the Christ’s stomach and perizoma (loincloth). It is a piece of carved wood that covers up a gap in the Christ’s support. This added piece is very well defined and there were doubts as to its function. After thinking about it with the Area’s team, the eventual conclusion was simple: the piece in the Christ was possibly a fragment of a long beam that had this hole so that another beam would fit in it. Analyses of the wood of the Christ’s support were made, and of a fragment of a beam from the church of Sant Vicenç, supplied to us by the local council of Capdella. The result was that it was the same type of wood, willow. We are therefore talking about a probable reuse of existing material, which was habitual in some Romanesque workshops that supplied themselves with material from the local area.

Photograph of a detail of the graft prior to restoration. Photo: Anna Carreras

Details of the process of opening the graft with the socket and with the carved piece that fits in it. Photo: Anna Carreras

The conservation-restoration process of this work has made it possible to carry out this study, done thanks to a thorough analysis based on perception and a detailed inspection of the work. The interdisciplinary scientific results of the analysis will help us to corroborate these hypotheses.

This carving, exceptional with regard to its size and quality, will very soon be exhibited in the rooms of the museum’s Romanesque permanent collection so that everybody can admire it.