Sandra Figueras

We have now spent more than 50 days confined in our homes by the Covid-19 health crisis, a new scenario and a reality that we are gradually getting used to. The boundaries of what we thought was possible have expanded and at the same time our everyday world has grown smaller, cut off from people and places outside the four walls of our home and living with the uncertainty of how long we will have to stay there and what ‘normality’ will mean when we emerge.

For all of us who remain confined, in these days the home has become a hyper-exploited space: we have turned it into an office, a children’s playground, a workshop, a laboratory, a studio, even a bar. We have observed it in detail, we have tidied it, or made it untidy, we have resumed projects that we had left unfinished, or we have simply observed it, the only landscape in these strange days. The halting of many activities and social relationships has led us to relate to our domestic space in many new ways and it has brought out the creativity of many people, as often happens in situations of uncertainty and helplessness. A good example of this is the initiative #tussenkunstenquarantaine, where thousands of people have staged in their home a work of art with the materials they had to hand.

Artists have often been shut up at home or in their studios; the nature of their work has to do precisely with tranquillity in order to observe, even in isolation, to allow them to develop ideas, reflect and think through processes of creation.

The English author Virginia Woolf said almost a century ago that, in order to create, to write, to think, we need “a room of our own”. This is true especially for women, often who often have to take care of a host of other domestic matters rather than their own creative urges.

In two very recent books the writer Mason Currey has compiled the customs and working routines of artists, writers and creators in general, examples of how domestic rituals and those of creation often have to coexist, particularly in the second one dedicated exclusively to women.

There is a dialogue in the spaces we live in, important for human beings in general and for creators in particular, if we understand it as something more than the backdrop to our existence. Now that we have paused to observe these domestic spaces, their rhythms, the footprints of our lives stored in them, the objects that accompany us in them, we may perhaps feel closer than ever to the works of art, the books, the music that many artists have made to talk about.

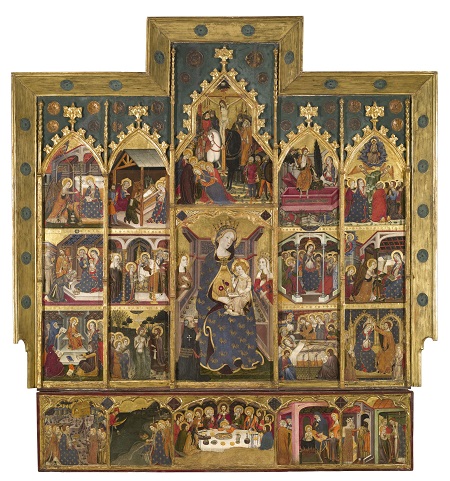

In the art of every period, even when the intention was to distance oneself from the human in order to portray the divine, the mysterious or the inaccessible, there have been niches in which to place everyday gestures and spaces. Painting in detail the cutlery, crockery and food on a well-laid table in a biblical scene, turning the divine gesture of the Virgin Mary into a mother caressing her son, or depicting holy figures in domestic settings from periods to which they did not belong are some examples of this.

There are, however, many points of reference in modern and contemporary art because it is self-referential art, which reflects one’s own possibilities and limits, fully conscious of the spaces in which it is generated and quite unconcerned about its power to represent the world. The French philosopher Merleau-Ponty named Paul Cézanne as the paradigm of this new gaze and the artist’s relationship with the world. No longer is it an outward gaze, a “physical-optical” relationship, he says, but an inward gaze. He calls his paintings “self-figurative”, they speak of the person painting them, they burst the skin of things to show how things are made and how the artist sees them. (Merleau-Ponty, The Eye and the Spirit, p. 52 quote p.50)

This shift from depicting what is visible to depicting what the artist feels or thinks will become increasingly pronounced. In contemporary art there are many examples of artists who not only wish to depict the world through themselves, they want to talk about themselves, to observe their “self”, explore their life stories, their places, their concerns. This is why the line that can be drawn between their daily world and the creative processes is perhaps clearer than ever and, in a situation like the one we are in these days, it is a relationship that we can share and which can accompany us.

Concerning the house and how we live in it

“In the life of a man, the house thrusts aside contingencies, its councils of continuity are unceasing. Without it, man would be a dispersed being. It maintains him through the storms of the heavens and through those of life. It is body and soul. It is the human being’s first world. ” Gaston Bachelard. The Poetics of Space, p.37 (citation on p.21)

The house is this significant, multidimensional place and the principal setting for our daily life. It may be understood as a building, as a symbolic place, or as the backdrop to family and social relationships, or it may be interpreted as a complex mixture of all of them. It is not just a building, an “inert box” (Bachelard, The Poetics of Space, p.79) better or worse designed, or more or less functional, but it must be seen as the place where our existence is housed.

There are philosophical currents such as phenomenology, which focuses on objects as manifestations of the consciousness, which enables us to understand the building for example as a lived, felt place, a habitat that influences the human activity that is carried out there, referring not only to events in daily life, but to reflexive and creative processes that take place there.

In the book The Poetics of Space (1957) Gaston Bachelard describes the house as a microcosm, “our corner of the world”, the place from where we gaze at and understand what is outside, it is the space where the sensitive world and the creative process connect.

Confined as we are to home, domestic gestures have multiplied, they seem more repetitive than ever, and at the same time they are becoming a source of inspiration for many people, a commonplace. The photographs and videos of these actions that we share on the networks have grown in number, turned into the meeting space that social distancing allows us.

Some artists, writers and musicians have taken this relationship to extremes with space and its working processes, taking refuge in remote spots or in tiny cabins where they develop their creative process.

The cabins of great twentieth-century thinkers were included in the exhibition project Cabins to Think (Fundación Seoane, 2011), an analysis of the minimal spaces and their surroundings where figures such as Virginia Woolf, Martin Heidegger, Knut Hamsun and Gustav Mahler worked. All of them illustrate the need to place restrictions on comfort and social relationships in order to achieve a certain degree of concentration. Recently, and closer to home, the artist and mathematician Pep Vidal also did this when in 2014 he shut himself up in a cabin to finish his doctoral thesis, turning the action itself into a work.

Whether in places for self-reclusion or in a city centre apartment, the idea of ‘dwelling’ is the hinge that enables us to understand person and place at the same time, an action fed by many others.

On 5 August 1951 the German philosopher Martin Heidegger gave the speech Building, Dwelling, Thinking. The Second World War was over, and in view of its devastation, he wished to make a profound reflection on how people could once again “dwell in the world”. He began his speech by analysing the meaning of the verb “to build”, which in German is derived from the word “bauen”. This ancient verb also means to dwell, remain, reside, and it also has connotations of shelter and protect, so it is the place where all of these actions intersect. The essence of the human being, says Heidegger, is dwelling. (Heidegger, M., “Building, Dwelling, Thinking” in Speeches and Articles, 1994 p.129).

Intimacy and the creative process

There are artists for whom awareness of place and of daily gestures is very much a part of the work they produce. Exploring their houses or their workshops can help us to sense what their creative process has generated and fed because it is where the thoughts, memories and dreams of the person who lives there coexist; they are the containers of their intimacy.

We speak about intimacy when the place takes us in and nourishes us, either alone or when it is capable of creating room for intimacy with others. Human geography has also considered these relationships. Yi Fu Tuan (linked) talks in his book of experience and intimacy (Yi Fu Tuan, Space and Place: the Perspective of Experience, 1977, p.137), and of art as a tool for sharing it because it allows us to make our place accessible to others, to make what belongs only to us universal. Art has the power to evoke places, to find the spaces that may be common to human beings and also to mark the places with their presence.

During confinement, hasn’t it been a consolation that other people have opened the doors of their houses or have shown us their workshops? To be able to see their bookshelves? To share in their rituals?

Ways of living and creating

Human beings try to materialize their ideas and their feelings in tangible things, to make the invisible visible.

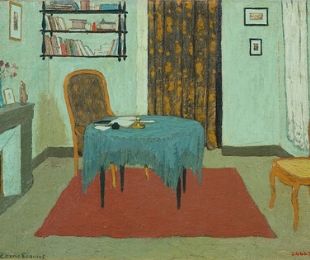

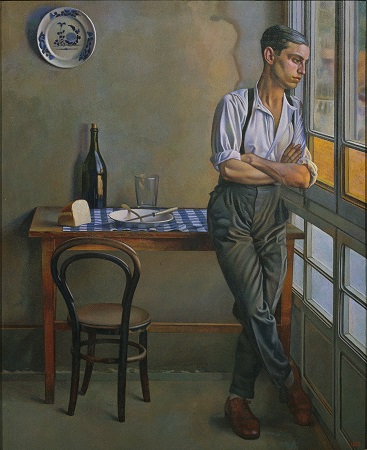

There are many examples of artists who have explored their most intimate surroundings: a room of one’s own is a constant motif in art, from the interiors of the Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer to Vincent van Gogh’s iconic bedroom in Arles. There are also examples in our collection: the strangely empty silent rooms of the painter Pere Torné Esquius or the many scenes of the family relaxing in the domestic surroundings of the painter from Tortosa Francesc Gimeno.

- Francesc Gimeno, Woman Sleeping, circa 1899

- Pere Torné Esquius, Interior, cap a 1913

But apart from depicting them, in more recent art quite different strategies have been used to reflect on these places. Ignasi Aballí, faced with what he calls the impossibility of painting, decides not to work in his studio, but to let the place speak; he collects detritus, waits for time to act on it, or for the dust to gather in it.

- Ignasi Aballí. Dust (10 Years in the Studio), 1995-2005

- View of Ignasi Aballí’s studio

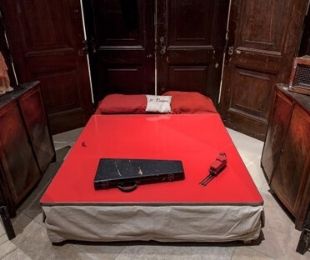

Louise Bourgeois and Tracey Emin take the story of their life, their intimacy, into the public domain of art. They share traumas, obsessions and family quarrels through their works. In the 1990s Louise Bourgeois created a series of half-open viewable cells, inhabited by objects and sculptures that turned them into disturbing bedrooms, rooms of the soul full of autobiographical references. That same decade Emin took the idea of the ready-made to greater extremes, transferring her bed and the rubbish around it directly to the museum, a provocative gesture that left no one in the public or the media indifferent.

- Louise Bourgeois, Red Room (Parents), 1994 (detail). Private collection, courtesy of Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Maximilian GeuterFoto: Maximilian Geuter. © The Easton Foundation / VEGAP, Madrid

- Tracey Emin. My bed, 1998. © Tracey Emin

Sometimes the domestic space has also been worked on directly. In the video 10 actions at home (2005) by the artists David Bestué and Marc Vives a strategy even more daring with space is brought into play. They turned it into working material. The video is a series of minimal acts full of a sense of humour and playfulness, among references to the history of art such as Dadaism or Bruce Nauman, and others from popular culture. The most ordinary places and objects are also part of the language of some installations by the artist Eulàlia Valldosera: dusters, detergent bottles, the objects on the kitchen worktop. The actions are made directly on the house, sometimes precariously with a minimal gesture.

- Bestué-Vives, Actions at home, 2005 (Vídeo/color/so/33’)

- Eulàlia Valldosera. Love (generated objects), 2008 (photograpy)

These are just some examples of how artists have related to their domestic spaces. The list could be a lot longer. In any case, these actions that directly relate living and creating illustrate the possibilities that this domestic space, now so present in our lives, can have. The house can be inspiring, even from the perspective of mandatory confinement, and it can give us valuable opportunities for reflection and creativity.

Related links

Louise Bourgeois exhibition at the Guggenheim Museum: Structures of Existence. The Cells

Servei educatiu