In the previous article we placed the fragments of mural painting from the group of San Pedro de Arlanza in context. In this article we shall discuss the recovery of the work in the storerooms, Pardus and architecture, and compare it to the piece in the permanent exhibition, the Griffin.

The two beasts: the Griffin and the Pardus

The Griffin from Arlanza has always been present at the end of the visit to the Romanesque Art permanent room. But why has the Pardus never been exhibited?

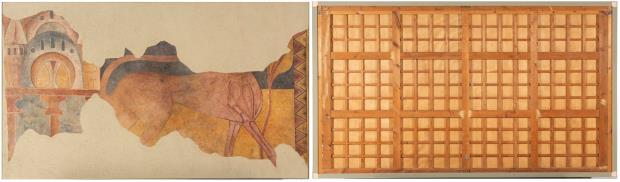

The two fresco mural paintings, stripped off and transferred, are very large.

The answer lies in the state of conservation of the two works, in the importance of the lost areas for understanding the depiction, and in the amount of original polychromy they offer. In the Griffin, conservation is stable and the amount of colour makes it possible to enjoy the creature; in the Pardus, conservation is very delicate and there is less original polychromy. The accumulation of traces of animal glue and wax on the surface were an impediment to the recovery of the fragment that was restored in 2018.

Why do the works have different supports?

The Griffin entered the museum in 1943 and the type of rigid support that was placed on the stripped-off and transferred fragments was a grid made of wood, cloth and plaster.

In the 1960s, the methodology used to make supports changed. The grid made of wood, cloth and plaster made way for a wood and plywood grid. This new, more rigid support was attached to the Pardus when the fragment entered the museum in 1973. The support of the Pardus is hygroscopic like the previous grid made of wood, cloth and plaster, but it offers a more even layer on which to lay the adhered mural fragment and is generally far lighter.

If the wooden support is more rigid and stable, why is the Pardus in a worse state of preservation?

The reason is the amount of crystallized glue on the polychromy.

Although the fragment is stuck to a more even support, the main problem lies in the traces of glue on the surface, which was used to strip off the pictorial film. So the fragment’s poor state of preservation is due to the glue, regardless of the rigid support on which it lies.

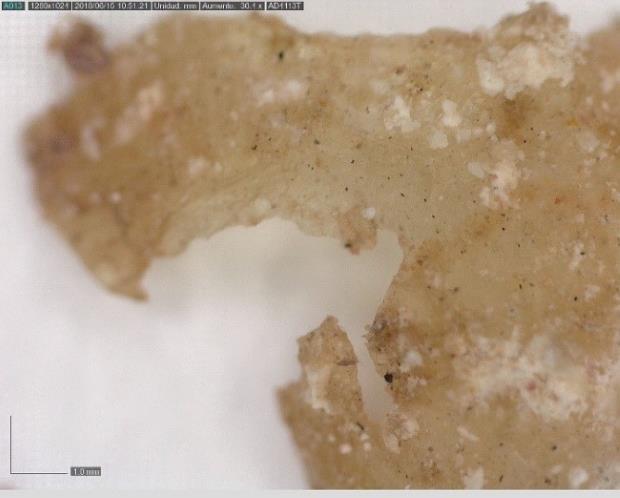

Animal glue is a protein binder that can be one of the worst enemies of mural paintings. It is an adhesive that has been used since Antiquity and it is still used today. It is a very safe product, as long as weather conditions make it possible to use it. You have to be very careful about preparing it and the percentage that is needed for the function is has to fulfil. In a mural painting any organic glue that is not removed from the surface crystallizes, cracks and, upon contracting, with the outward force it takes the polychromy with it. The thickness of this material and its penetration when applied hot creates a skin that adheres to polychromy that is just a few microns thick.

The laboratory results obtained in samples from Pardus and architecture, stripped off in 1942, were illustrative: the materials on the surface were basically animal glue and wax. The two products were used in the stripping off process or placing it on the new support, or in both processes.

The conclusions show fundamentally that the thickness of the glue can be associated with:

- The complicated removal from the wall. More organic glue was used in the removal than with the fragment of the Griffin

- The difficult adherence of the transferred fragment when it was placed on the rigid support.

Restoration of the Pardus and architecture

The restoration work in 1998

The first intervention by the museum in 1998 is documented, but the trials carried out to remove the glue resulted in an important loss of original polychromy and so the work was halted – an honest decision, to avoid the loss of information, which is habitual in conservation-restoration. Subsequent advances often make it possible to resume the process with more guarantees.

For this trial the protein binder was softened with a compress for 10 minutes and then removed mechanically with a scalpel. With an acrylic microemulsion, Primal AC33, dissolved 10% in distilled water, the paint layer was fixed.

The restoration work in 2018

The project AcercArlanza (L127-24/2018), which consisted in making photographic reproductions of the paintings in the museum, turned out to be an excellent opportunity to restore the group of fragments and to meticulously tackle the restoration of the Pardus, despite the complexity of the task.

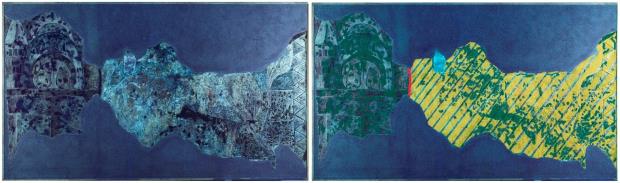

Right. State of preservation. Graphic: Paz Marquès. Legend:

1. Yellow strips, sloping, animal glue on the surface

2. green, colour restoration

3. light blue, the earlier intervention

4. red, the separation of the two fragments

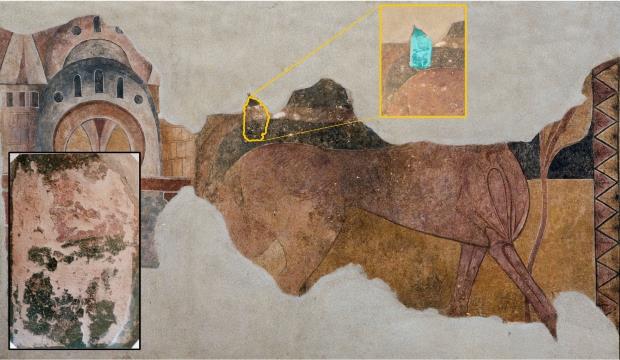

The preliminary studies consisted in graphic documentation – photographs with visible light, raking light, ultraviolet light, of details, images with surface microscope – and the study of the materials in the laboratory. After the research was done the restoration began, even though it was obvious that some areas of the polychromy could not be recovered.

The diagnosis of the work’s state of preservation had not changed: cracks and flaking caused by the glue and altered and fairly widespread colour restorations. Despite the inevitable original paint loss it was important to remove as much glue as possible to improve the state of preservation.

The process consisted in softening the adhesive with agar jelly and removing it mechanically with a scalpel. The losses were levelled with lime stucco and animal glue dissolved 6% in water, and colour restoration was done by stippling with W&N watercolours. The colouring of the neutral area, free of traces of paint, was done by speckling with a paintbrush.

Two creatures, one model

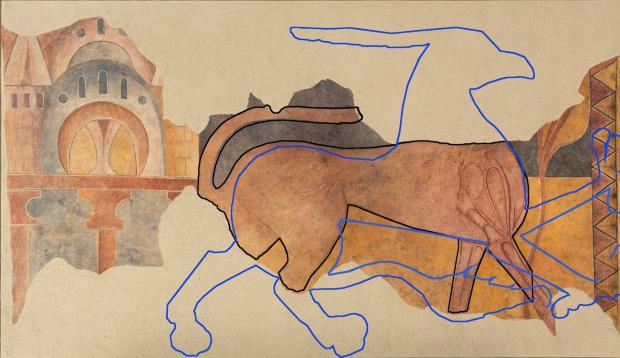

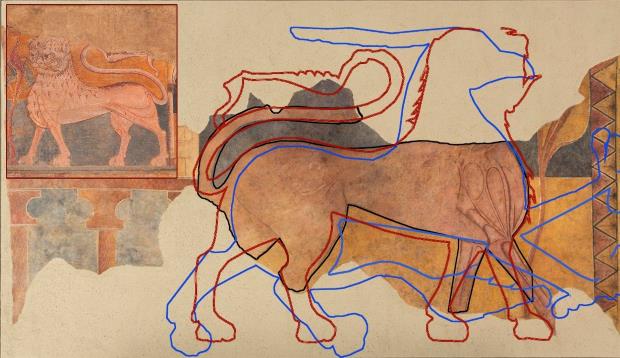

The Griffin and the Pardus are drawn based on the same model.

It is well known that artists in general, and muralists too, made use of models and patterns to make and fit their figures and compositions. To the naked eye, without making any superimposition, the similarity of the figures is evident.

The Griffin shows us an animal with an eagle’s neck and beak and a body with the claws of a lion; the shape of the Pardus’s body and tail is the same although it is headless and we cannot see the bottoms of the legs. Digital processing helps us to corroborate that it is the same animal.

The Pardus is only about 2 cm longer from the start of the neck to the hindquarters. Whereas the Griffin seems to be a moving figure, the Pardus, with all four feet on the ground, seems to be standing still. On the winged Griffin, we see the eagle’s neck and head, while on the Pardus we cannot see either of the two elements.

Three creatures, one model

What happens if we superimpose the body of the Lion that was sold in New York on the two creatures in the museum? Although it is facing the other way round, we only have to flip it to make the use of the same model even more obvious. We have the exact measurements of the griffin and the pardus. Without having those of the lion, making the animal the same scale shows us the same body. The feet on the ground and the movement of the lion’s tail are the same as in the drawing of the pardus.

These two works and the other fragments from Arlanza are now a group of delicate but stable pieces. They have been restored and are divided between the Romanesque Art permanent room and the museum’s large-format storeroom.

Although they are two works in different places in the museum, are you not curious to enjoy seeing them together?

Related links

An extraordinary bestiary: San Pedro de Arlanza. «Griffin» and «Pardus and architecture» / 1

The mural painting transfer kitchen

Restauració pintura mural