Daniel Vilarrúbias

The chest was perhaps the container par excellence in Catalonia in the early modern period, since the type appears in the mid 15th century, coexisting with iron-bound or heavier-looking chests, and it disappears in the middle of the 18th century, when the wardrobe became widespread and the chest of drawers suddenly appeared, dressing room furniture that was more suitable for keeping clothes in.

The formal and decorative development of chests can be followed throughout the early modern period, and, as the expert Eva Pascual has pointed out, it is perhaps one of the few areas where this happens so continuously throughout such a long timespan. Both post-mortem inventories of the goods in a house and some interiors depicted in paintings reveal that the proportion of chests and containers in houses was far greater than that of tables and other kinds of furniture, from the late 15th century onwards at least.

There were two main types of chest, those with two panels separated by a moulded upright (mig cofre), and those with three panels (cofre major); we believe that the inside of the latter measured about one cana, which in Barcelona was the equivalent of 156 cm.

The bride’s chest with the Annunciation in the Museu Nacional

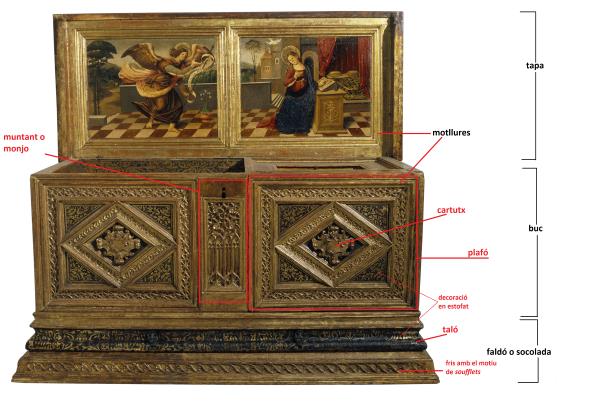

In the Museu Nacional’s permanent exhibition there is a splendid example of a walnut bride’s chest – or perhaps poplar. As a mig cofre its front has two panels separated by the upright or monjo decorated with fretted tracery, and the entire piece was raised off the floor by a very powerful and striking high moulded and fretted plinth, giving it a maximum width of 140 cm.

The right-hand half is compartmentalized with drawers opening from the corresponding front panel, which acts as a door. These characteristics and the presence of moulded lozenges as the main decoration of the surface of the panels refers us to the type of flat lidded, moulded chest that originated in the 15th century and was developed during the second half of that century. Some ornamental details, however, suggest a later evolution of this model, which was made until the 1540s and even later. Supporting this hypothesis are the general gilding of the entire piece of furniture, the subtle flattening of the relief of the mouldings (strip, half cane and fillet), the presence of talon mouldings on the plinth, especially the one that appears polychromed in blue on gold in the centre of it, the stylization of the lozenges, which here have been flattened to occupy the entire panel, the estofat floral motifs at different points of the piece and the paintings on the inside of the lid. The tradition of painting this part of chests meant that these pieces of furniture formed part of a well-to-do household’s furnishings and that they were usually shown open, and, if necessary, a simpler second lid was made for them, in order to hide the content of the chest.

This chest would be a luxurious product almost certainly made in workshops in Barcelona in the first half of the 16th century. To be precise, I would date the piece to between 1500 and 1520, but this one must have been worked on later: the year 1548 appears in the painting on the lid (quite notable in itself and which would perhaps be deserving of a separate study), in the grotesque decoration of the die the Virgin Mary is leaning against. Moreover, the moulding of this lid is quite a lot flatter and does not go with the work on the front and the plinth. In any case, done in two stages or in a single one, it is a piece of furniture typologically earlier than the chests decorated with portraits that began to appear around 1540.

Other Catalan bride’s chests

Of the chests decorated with portraits, the one in the Museu Episcopal de Vic, attributed to the painting workshop of Perot Gascó (1526-1546), has become the paradigmatic piece and perhaps the oldest one to have survived, even though the original plinth has been lost.

The piece that most closely matches the chest we are talking about appears photographed in 1923 in the file on a chest in the Amatller Institute of Hispanic Art, a piece that was then conserved in the Castle of Santa Florentina in Canet de Mar (I do not know if it is still there). The panels with lozenges and a cartouche inside are so similar that they could almost be considered to have come from the same workshop.

Also showing close typological links to the piece we are looking at is the bride’s chest in the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, which appears catalogued as an anonymous Cassone from northern Italy, circa 1510-1520. I consider it to be a Catalan work contemporaneous to the one we are studying, produced in a workshop very close by and, at the most, with a lid repainted or changed very soon after the chest, which has lost its plinth, was made.

If we seek decorative parallels for the fretwork and the plinth, a few examples could be found in the Museu del Disseny HUB in Barcelona. For example, the continuous frieze of soufflets that we find on the bottom of the plinth is almost identical to the one on the Saint Philip and Saint Bartholomew chest with drawers and also on the plinth of chest no. 4981 in the Museu Episcopal de Vic.

We find the large pronounced talons with estofat blue gilding on the chests The Annunciation (circa 1550) and The Nativity and the Epiphany (between 1520 and 1550), the latter being the one that shows a greater degree of similarity to the one in the Museu Nacional.

On the other hand, the sculpted cartouches that we find inserted inside the lozenges involve carved decoration along the lines of what can be seen on the chest The Annunciation, by the circle of Pere Nunyes and Enrique Fernández, which has traditionally been dated to between 1520 and 1550.

The Annunciation 1525-1550. Museu de les Arts Decoratives de Barcelona. Fotografia: CRBMC – Enric Gracia

In the late 19th century, it was fashionable (de bon to, to use an expression of Mn. Gudiol) to have pieces of Gothic or Renaissance furniture in well-to-do houses, and they were therefore highly sought after and coveted. Due to this fashion, they often appear greatly repaired and retouched. In the words of the museologist from Vic: “For many years it has been fashionable to possess an old piece of furniture to decorate a workshop or a lounge. That was the reason they were sought after and when something interesting was found, not only was it unearthed and restored, but it was also completed and even taken apart and used to mend capricious items of furniture that, although they contained really old parts, should be considered, if not falsifications, at least examples that are useless for the archaeologist or the artist.”

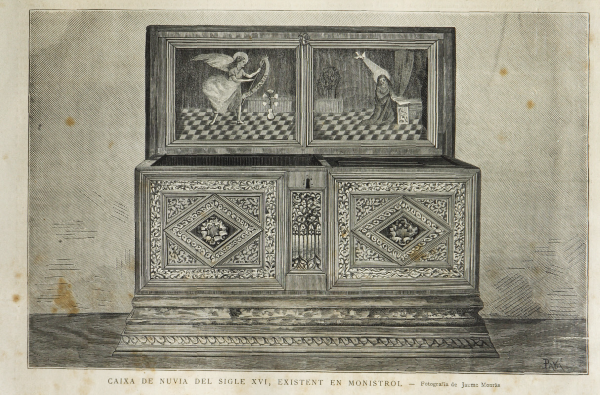

In our case, on the other hand, the piece has survived in a fairly original state. We have information about this piece going back a long way, because it aroused the interest of those who saw it. In 1881 it appeared reproduced on the pages of the newspaper La Il·lustració Catalana, in an article by Eduard Támaro, who also tells us about its owner: “this chest which is meticulously conserved in the house of D. Francisco Plá, the well-known owner of Monistrol de Montserrat”. This person purchased part of the old palace of the abbots of Montserrat, called the “Palau prioral” or “La Sala”, and he refurbished it to convert it into his residence according to the style of the late 19th century. In any case, we do not know if this chest came from an antiques dealer or whether Francesc Pla found it there when he purchased the property in Monistrol. Nor do we know how it ended up in the possession of the person who left it to the Museu Nacional in 1966, Alberto Par Espina.

Related links

New display of Renaissance and Baroque . Medieval inertia