Alícia Cornet

The ukiyo-e in context

A ukiyo-e is a type of xylographic printing in colour that was produced in Japan during the Edo period (1603-1868) and the Meiji period (1868-1912).

During the period of stability and peace that Japan lived in the Edo period, governed by the Tokugawa family, this led to the growth of the economy and the increase in the population in urban settings. Various factors contributed to this: the move of the government to Edo, present day Tokyo, the commercial isolation that Japan underwent during this period, and the new system of residence for the feudal lords.

In 1603, the emperor conceded the title of shogun (generalissimo) to Ieyasu Tokugawa who imposed a military government with its headquarters in Edo and isolated Japan from the outside world. The ban on Japan from trading with foreign powers caused traders to have the monopoly on the Japanese market and, as a result, significantly increased their economic power.

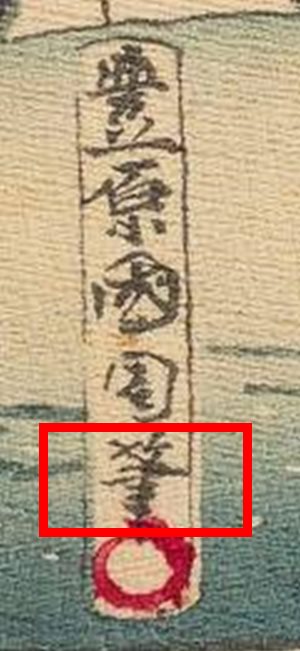

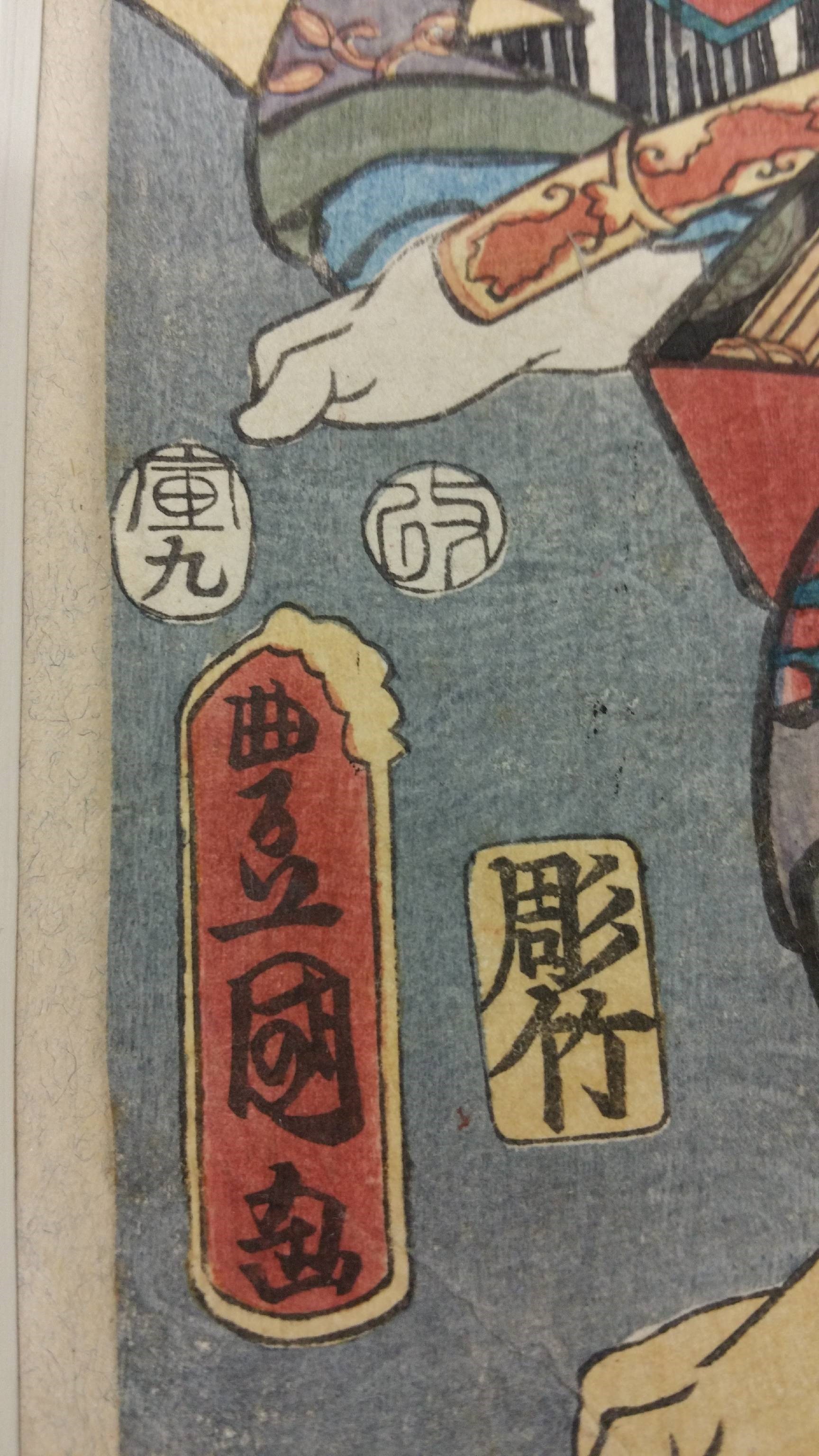

Detail of engraving Yaomatsu Restaurant in Makurabashi (Thirty-six Modern Restaurants) by Toyohara Kunichika, circa 1878

A new system of residence was restored in 1635 for the feudal lords (Daimyō) which obliged them to reside in the city during alternate years to serve the shogún. While they lived in the city, the feudal lords, accompanied by their entourage and families, became wealthy craftsmen and merchants. By the end of the year, they could return to their fiefdoms, but their families remained in the city. The trips between Edo and the fiefdoms were expensive and, for this reason, the feudal lords lost their purchasing power and had to apply for loans to wealthy merchants.

The cities increased their population, a part of the craftsmen and merchants became wealthy, and around the cities, a new social group was formed, the chonin (people of the city), who played a fundamental role in the appearance of a new culture far from the rigidity of the traditional culture.

Cities such as Edo, Kioto and Osaka, filled their centres with entertainment centres where the residents could enjoy their leisure time contemplating representations by the kabuki theatre, sumo fights or visiting the neighbourhoods of pleasure. But not all the households had the purchasing power to enjoy the entertainment offered by the city and the alternative to these was the ukiyo-e.

Themes of the prints

The themes of the prints were a reflection of the lifestyle of the wealthiest inhabitants of the city. Scenes from the kabuki theatre with their actors (yakusha-e) were one of the most represented themes, as well as the genre of pretty women (bijin-ga) in which very often the protagonists were the elegant courtiers from the neighbourhoods of pleasure.

Kikugawa Eizan, Cortesana. Forms part of an album with seventy prints, end of the 18th century – mid-19th century

The ukiyo-e had a major impact on the society of the time. We have to think that the actors of the kabuki theatre were considered to be super stars, with fans who followed and admired them, and that the women represented on the prints in their kimonos, make-up and hairstyles, marked trends in the fashion of the time. Thus, the ukiyo-e would be like our magazines and thanks to their massive production and low cost, could be acquired by all the sectors of the Japanese society.

In addition to topics related to the theatre and the female figure, the artists of the prints represented scenes inspired by legends, mythology and historic events, as well as landscapes (fukei-ga) and war scenes (musha-e), amongst others.

Utagawa Kunitsuna, Death of Imagawa Yoshimoto in the Battle of Okehazama (Okehazama no honjin Imagawa Yoshimoto uchijimi zu), circa 1840-1868

Elaboration of a ukiyo-e

To elaborate a ukiyo-e the following process was followed:

- the editor commissioned a project to the artist, who produced a preliminary drawing and showed it to the editor for his approval.

- from 1791 onwards, the drawings had to pass an inspection of censorship prior to being printed, and if approved, the drawing returned to the editor with a stamped seal.

- then, the engraver cut the whole drawing on the plate, printed a proof, in which the artist marked the areas of colours, and after that cut the corresponding plate to these.

- finally the printer carried out the printing on paper.

Therefore, the ukiyo-e was the result of the collaboration of various professionals who placed on record their participation by means of inscriptions and seals. Interpreting them will be the aim of the rest of the article. To do so, we will be helped by the Japanese prints of the museum.

Even though we will only mention some of these prints, we should point out that the museums conserves an important collection of Japanese prints in its Department of Drawings and Prints, from among which it is worth highlighting, due to their beauty, those related to the topic of bijin-ga (pretty women) acquired from the Japanese pavilion of the Universal Exposition of Barcelona in 1888.

The signature of the artist

The artists usually signed the ukiyo-e with a combination of kanji (Japanese characters) presented vertically that ended with the suffix ga or hitsu which means “drawn/painted by”.

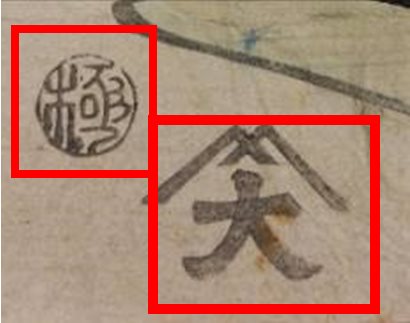

In the Yaomatsu Restaurant in Makurabashi (Thirty-six Modern Restaurants) engraving that we see on these lines, we can observe the suffix hitsu on a red circle, the Toshidama, a seal used by members of the Utagawa painting school.

The artists were charged with the elaboration of the design, they didn’t cut or print the engraving. They adopted an artistic name (gô) to sign their works, which would change during their professional life. In the case of Utagawa Kunisada , one of the most prolific authors of ukiyo-e from the Edo period, his birth name was Tsunoda Shozo, but adopted different gô to sign his prints such as Kunisada and Toyokuni.

The different names used by the artists can be linked to events in their lives. For example the print of Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, one of the major innovators of Japanese printing in the Meiji period, is signed with the gô: Ikkaisai Yoshitoshi. It seems that Yoshitoshi suffered a deep depression at the beginning of the 1870s, and around 1873, he overcame the illness and Yoshitoshi was able to return to his work, adopting a new artistic name: Taiso, which means “great resurrection”.

The seal of the editor

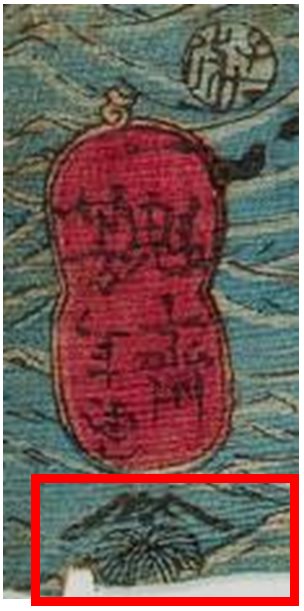

Continuing with the print of Yoshitoshi, below the signature of the artist, we can observe the emblem of the editor Tsuta-ya Kichizō, one of the most important businessmen of the 16th century. He was the owner of the publisher Kōeidō and published prints by artists such as Hiroshige, Eisen and Kunisada, among others.

The publishers were key figures in the elaboration process of the ukiyo-e. They financed and supervised the whole production process, chose the theme of the print, and the artist produced the drawing, supplied the materials, coordinated the craftsmen and distributed the prints.

The artists of prints were not very socially recognised at the time. They worked for the editor and his evaluation was linked with the success of the publishing project. If the artist depended on the editor, the editor would depend on the customer who bought the works. Therefore, the editor had to be well aware of the tastes of the period, given that a bad choice of theme could be the cause for the failure of the project.

During the Edo period, a large number of publishers were concentrated in Tokyo who, so as to distinguish their prints, stamped their distinctive seal which could be anything from a simple drawing to a description with the name, address and professional merits of the publisher.

We can observe the emblem of the publisher Daikokuya on the print of Keisai Eisen (1790–1848) (fig.7). Even though the beginnings of the publisher date back to 1764, it was around 1840 when they started to produce prints on a large scale and to work with important artists such as Kunisada and Eisen.

El segell del censor

During the Edo period, Japan was governed by the Tokugawa family, who, to avoid any kind of subversive movement that could place their government in danger, imposed strict measures of censorship. From 1790 onwards, it was obligatory for anything that was to be printed to pass an inspection. They were the same members of the publishers’ guild, so as to avoid fines and prison sentences, self-censored themselves. The originals that passed the inspection were marked with a round seal with the character kiwame (approved).

The censorship seal was used between 1790 and 1876 and during this period the contents and quantity varied. These changes help us, in most cases, to know the date that the ukiyo-e was produced.

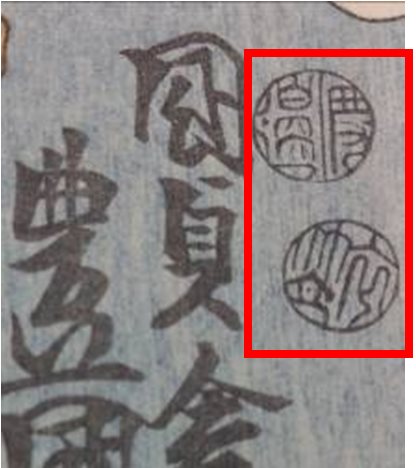

For example, in the print of Kunisada, instead of one censorship seal there appear two, the consequence of the tightening up of the censorship from 1842 onwards, the censors became civil servants and marked the drawings with personal stamps. In the case of the print of Kunisada, the seals correspond to the civil servants Watanabe and Kinugasa who carried out the function of censors between 1849 and 1850, so it can be deduced that the print was produced between these two dates.

From 1853, the personal seals of the censors would disappear and the most used would be those that included the character aratame (examined). This seal could be accompanied by another with the date, as we can observe in the print number 10 also of Utagawa Kunisada. In this engraving, the date seal includes a kanji that represents the tiger, which corresponds to the year, and below, the kanji of the new number, which corresponds to the month.

Detail of Yuranosuke, Kumagai and Jiraiya by Utagawa Kunisada. Date in the circle on the left and flip it in the circle on the right

The Japanese used the Chinese calendar which is based on cycles of 60 years, which likewise are divided in five cycles of twelve years. Each year is associated with an animal and, therefore, this is repeated each twelve years. For this reason, in the moment of trying to date a print, we can find the same animal linked to different years. So, to calculate the exact year of ukiyo-e, we have to focus on other details such as the gô that the artist used or the personal seal of the censor.

Continuing with the print of Kunisada, the years associated with the tiger (during the period in which they used the seals with dates) are 1806, 1818, 1830, 1842, 1854, 1866 and 1878. Kunisada lived between 1786 and 1865 so we can therefore eliminate the last two years. The engraving is signed Toyokuni ga and has the Toshidama (seal used by the members of the Utagawa school) surrounding the name. This signature was used by the artist between 1850 and 1860. If, in addition, we add the fact that from 1853 onwards the most used seals were the aratame and the date, we can deduce that the print was produced in 1854.

We have talked about the professionals who intervened in the elaboration of the ukiyo-e and how they left a record of their participation. But other inscriptions appear that refer to the characters and places represented, as well as the title of the project that they formed part of. We will talk about this in another article.

Enllaços relacionats

Identifying a Japanese print, Diego M. Santos

La colección de grabados yakusha-e del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Sergio Navarro, Butlletí del Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, 1993

Ukiyo-e in Madrid: Japanese prints from the Museo Nacional de Arte Moderno and its legacy in the Museo Nacional del Prado, Ricard Bru, Newsletter of the Museo del Prado, 2011

Documentació