Àngels Comella i Jordi Camps

Image of the work before and after restoration

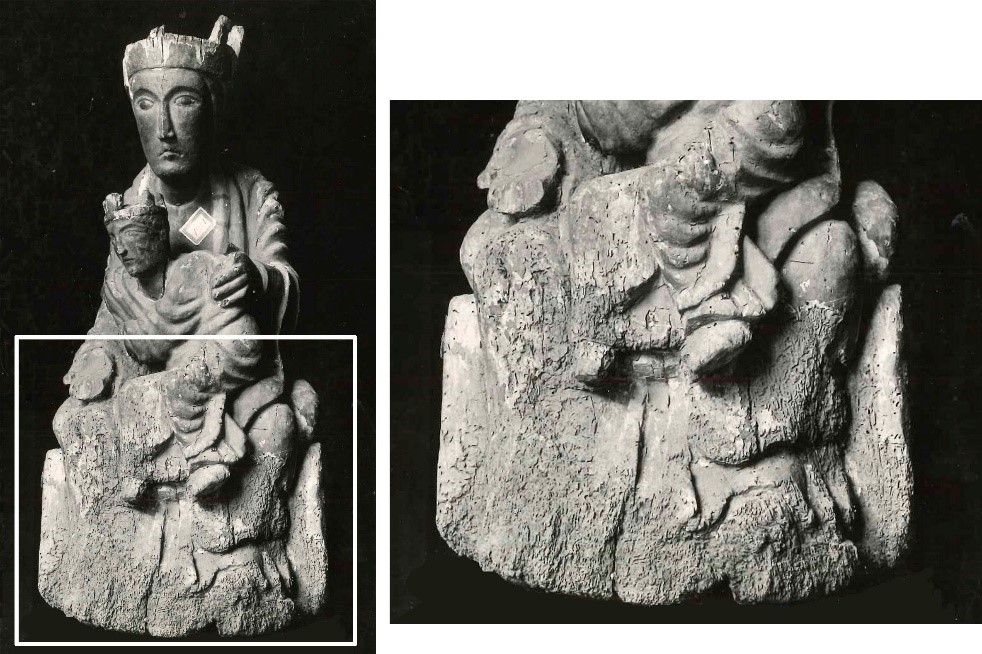

A crowned Child Jesus about to get down from his mother’s lap is the feature that characterizes a Romanesque image that entered the museum in 1920, after the Museums Board had purchased it from the antiques dealer Josep Valenciano. It is a polychrome hardwood carving, with a very interesting conception and technical quality. Before the restoration process in 2018, it was in the storageroom because it was covered in so much dirt, and its colour and volume had been changed so much, that it could not be exhibited.

We study the work

In a first examination, we observed that restoration work had been carried out on it several times. On one occasion it had been particularly invasive and this was affecting the correct interpretation of the piece.

Although there is no written documentation about the restoration processes to which the work has been subjected, there are photographs from the time when it entered the museum. The study of this photographic documentation, as well as the visual diagnosis, the chemical analyses and the radiographic study that we carried out were crucial for drafting a proposal for restoration with the aim of returning the object as far as possible to its original appearance.

What does the archive material tell us?

The black and white image enables us to see that the carving came to the museum in a very bad condition, with a considerable mutilation of the volumes: it presented a devastating attack by xylophagous insects, with important losses of the support and the polychromy. Moreover, the visible picture layer was not original, but a repaint probably datable to the 18th century.

Extreme restoration work

After the woodcarving entered the museum, in 1920, restoration work was carried out that consisted in stuccoing and reconstructing with plaster many of the losses of the support, even lost volumes like for example the feet and part of the belt of the Virgin’s tunic. Then, the whole of the stuccoed part, part of the exposed wood and in the existing polychromy some areas were repainted.

This restoration affected approximately 60% of the surface of the carving. It was without doubt an excessive reconstruction that spoiled and considerably altered the appearance of the Virgin with the Child, using criteria far removed from those of minimal intervention, which are now observed.

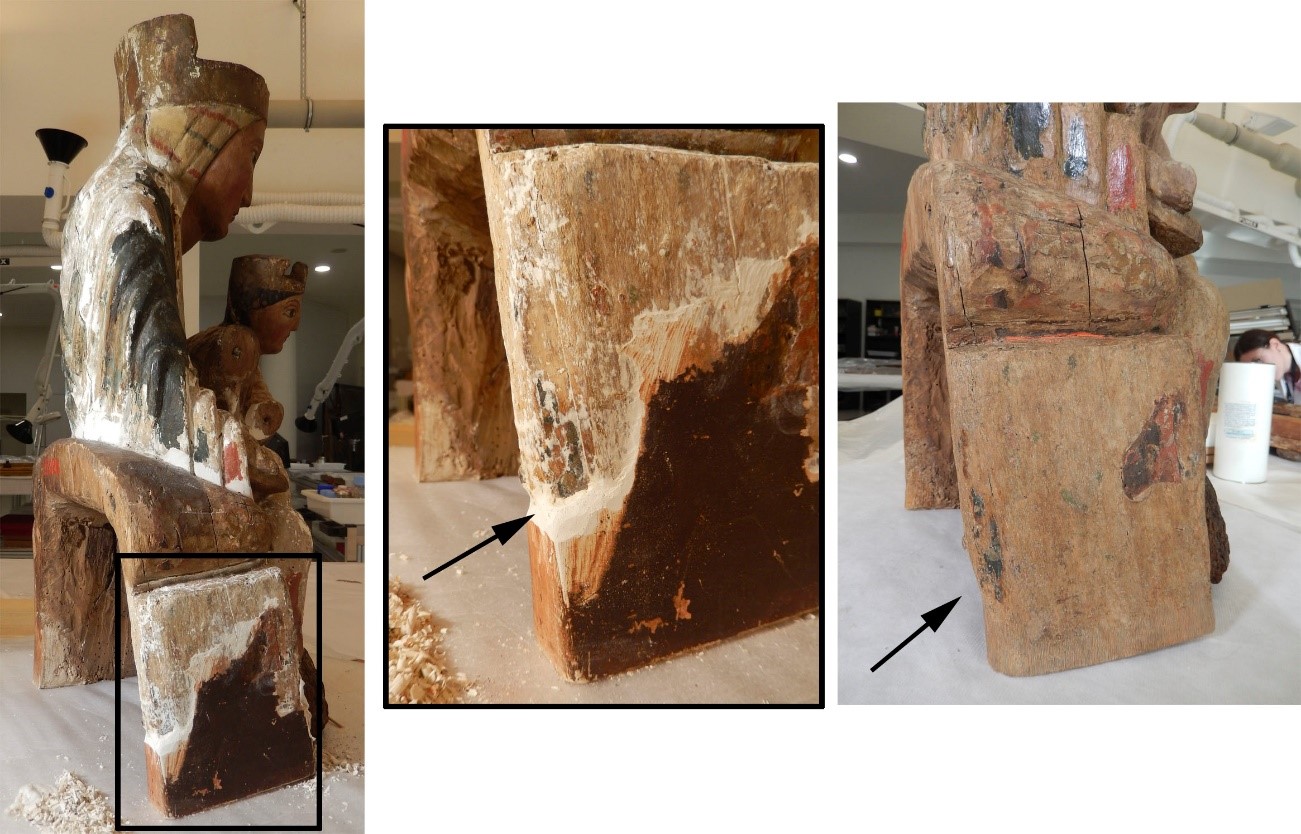

The X-ray image (XR) was fundamental in the approach to our work because it revealed exactly what condition the wooden support beneath the layer of plaster was in. Radiography clearly showed us the different thicknesses of added plaster and we reached the conclusion that most of the carving, although damaged, was still quite intact and we were therefore able to consider recovering the volumes of the original woodcarving.

Details of the work in an X-ray. The intensity of the blue indicates a greater accumulation of plaster (X-ray: Comella, Martí, Masalles)

The proposal for restoring the Virgin was based on the following stages:

- Removal of the inpainting and the surplus stucco from the previous restoration in order to recover the original carving

- Cleaning the remaining polychromy

- Levelling with stucco, in places where it was necessary

- Inpainting

The restoration process

The surplus plaster was removed by moistening the surface gently with a swab and deionized water, and by using a scalpel. We reduced the thickness of the stucco down to the original volumes, wherever possible recovering the traces of old polychromy.

General view, detail and end of the process of stucco removal and repair of the work. The removal of stucco revealed traces of old polychromy

The cleaning was initially done with an aqueous system, and later with the use of solvents in some areas.

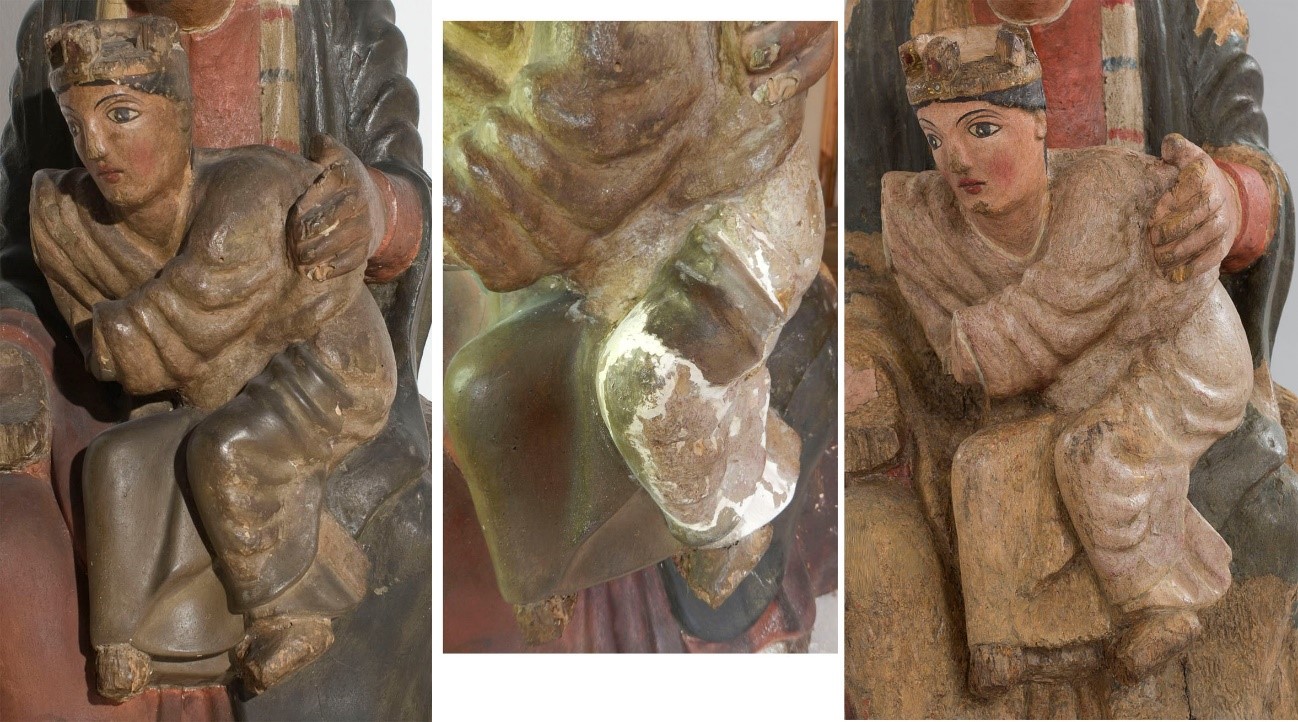

Detail of the Child before the current restoration (left), cleaning/stucco removal process (centre) and now with the inpainting (right)

What do we know about the polychromy?

The chemical analyses of the pigments confirmed that the technique used in the visible picture layer was oil paint. Beneath this last layer we identified some remains of older polychromy: with oil as the agglutinant, principally, and some traces with egg tempera which could date from the period when the work was made (on the Virgin’s seat and below the Child’s tunic). In a sample taken from the Virgin’s crown a thin strip of tin was identified beneath the visible layer of orpiment, and this suggests that the crown could have originally been gilded using Mecca gilded tin and that it was later repainted yellow.

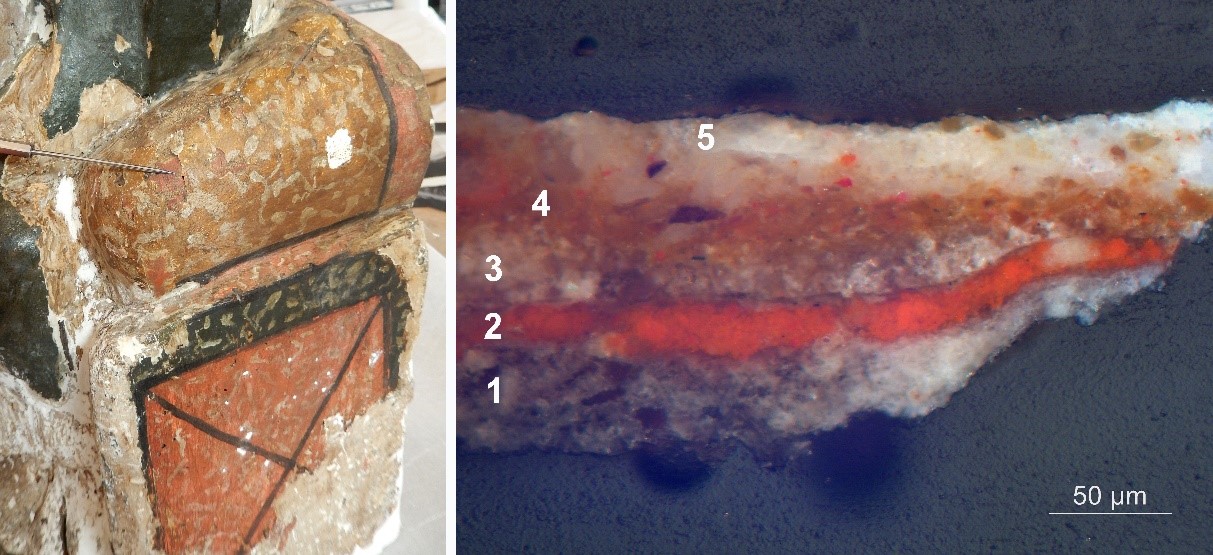

Location of the point of extraction of a sample from the left-hand side of the Virgin’s seat. In the image of the stratigraphy the superimposition of different layers can be observed. (analysis: Núria Oriols)

| capa 5 | polychromy with lead white and oil |

| capa 4 | ochre polychromy composed of lead white and earth-coloured pigments |

| capa 3 | plaster |

| capa 2 | red polychromy with the pigment minimum and particles of cinnabar/vermilion |

| capa 1 | plaster |

The final presentation

The inpainting has been limited to blending the whites of the stucco, adjusting them according to the colours of the surrounding areas. With regard to the gaps, where the stuccoed surface was considerable, we have used the inpainting technique called tratteggio.

Since it is a work that has been worshipped for centuries, we believe it must have been repainted to mitigate the damage due to the passage of time, or even to keep up with changing fashions. On the Virgin’s back, the two peg holes, which can be seen above the hollow area corresponding to the seat, suggest that the carving was attached to a panel or that this void was simply covered with wood.

The principal objective of our work has been to recover, as far as possible, the appearance of the original work and to remove both the excess dirt and the altered colours, for the purpose of making this attractive woodcarving, which is on display again, as easy to interpret as possible.

A work of unknown origins

While the image was being analysed and restored, it was necessary to study it to discover the purpose for which it was created. Knowledge of and comparison with other works and themes formed the basis of the work. Let us not forget that works come to museums removed from their original context. Modern documents tell us that the carving comes from the western Catalan Pyrenees, although for the time being it is impossible to pinpoint its origins, unless a document or a photograph appears in future to enable us to identify it.

However, its peculiarity lies in the fact that the position of the Child is not the usual one, which is seated in Mary’s lap or on one of her knees, facing the observer. In this case the figure is leaning to the left, with his hands open, clearly facing another figure that is addressing him from that side. The group, then, shows a dynamism and an apparent ease of gestures that are non-existent in so many Virgins from the Romanesque period, marked by their frontal nature.

The image and the scene of the Adoration of the Magi

In the state that they have survived and as we can observe them today in museums, we might think that the images of the Virgin with the Child appeared as a separate object on the altar. They were, however, often combined with other representations. One of these was the Adoration of the Magi, in which the figure of the Child leans and stretches out his arms to solemnly receive the offering of the first one, Melchior, as we see in the scene represented on capitals in Saint-Lazare in Autun (Burgundy) or the cloister of Tarragona Cathedral. Therefore, the carving we are analysing may very well have been part of a group like this. Other wooden images, like the one from Santa Coloma in Andorra, have a composition that is similar but not identical to the one of our museum.

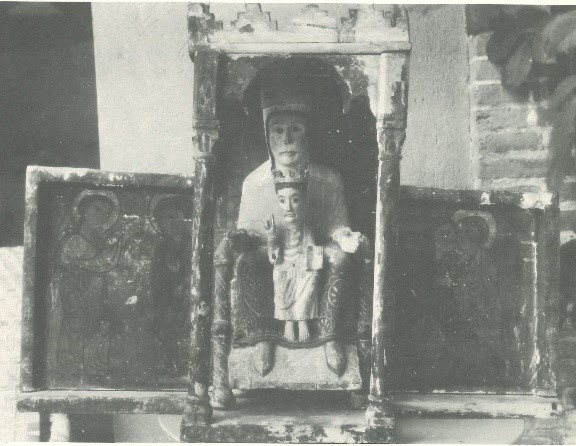

A model for a structure on an altarpiece, or aedicule

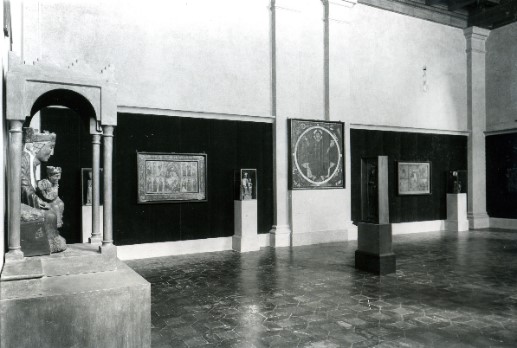

There are some very interesting examples in which the image is set inside a niche-like structure, thus forming part of a small altarpiece or aedicule along with other scenes. A partially conserved example, a sort of small altarpiece, is the one from Sant Martí in Envalls (Angostrina), in French Cerdanya. The group of the Virgin, in this case with a strictly frontal composition, was accompanied by the scenes of the Annunciation and the Visitation, painted on two side panels. Unfortunately, the woodcarving was stolen in the 1970s. We mention this example because it served as a model, through a drawing by the artist Sebastià Junyent, for building a wooden structure in the form of a niche that framed the image when it was exhibited in the 1920s. Therefore, our image is also interesting from the museographical point of view, seeing as the museum exhibited it for many years attempting to evoke part of its initial context.

A note of movement in the Romanesque galleries

Stylistically, the group combines the severe or solemn expression of the figures, somewhat schematic, with the naturalness of the gesture in the figure of Jesus. Moreover, his clothing was carved in the form of multiple creases. Therefore, we can propose a date for this image of around the year 1200 or the early decades of the 13th century.

As we have seen, the image has its own history in the museum. Now, newly displayed in the Romanesque rooms, with its splendour recovered, with its dynamic composition, it contributes new content alongside the medieval Virgins of Ger, Matadars, Gósol and All.

Jordi Camps

Medieval Art

&

Conservació-restauració