Sílvia Tena

A little bit of history

The office of registrar (an English term that derives from its American origins and influence) came into being in the late nineteenth century, although its roots are buried deep in the European royal collections and cabinets of curiosities of the eighteenth century.

In 1881 the US National Museum in Washington DC (today known as the Art and Industries Building in the Smithsonian Museum) opened and, for the first time in history, it included among its staff what was called a “Registry office”. Its co-director G. Brown Goode firmly defended the creation of a system of universal and standardized access to collections. In 1895 Brown Goode, heavily influenced by the South Kensington Museum in London (now known as the Victoria and Albert Museum), drafted a document, Principles of Museum Administration, in which he laid the foundations that were to underpin the subsequent philosophy with regard to collections management, based on the premise that the value of a collection depends to a very large extent on the accuracy and level of introduction of the documentary history of all the objects it contains. Therefore, a specimen in a collection without a corpus of documents and an inventory with which to be associated is a virtually worthless object, seeing as it is not accessible to be visited or studied. It is unlisted, unknown and, when all is said and done, lost.

In the early twentieth century, helped by the growth of communications, American and European museums began to move collections to public exhibitions and events. At the same time, museum workers began to devise standardized systems for inventorying, documenting and arranging their collections in order to have them controlled and make them universally accessible.

The initiative was taken by the science and natural history museums, and they were followed by museums of all kinds until, in the 1910s, the “Registry” started to become a fundamental competence of a museum’s basic work. The Metropolitan Museum, in the April 1907 Bulletin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, mentions that since 1905 it has had a Registrar’s Office, and it establishes that “all the art objects that are admitted through donation, purchase or loan, are received by the Registrar’s Office. If they are rejected, they are returned to the owner by the same unit or department. After the museum’s Board of Directors has accepted an object, the Registrar will immediately give it a number, enter it in the collections inventory book, and send it to the photographer’s studio so that he may photograph and label it.”

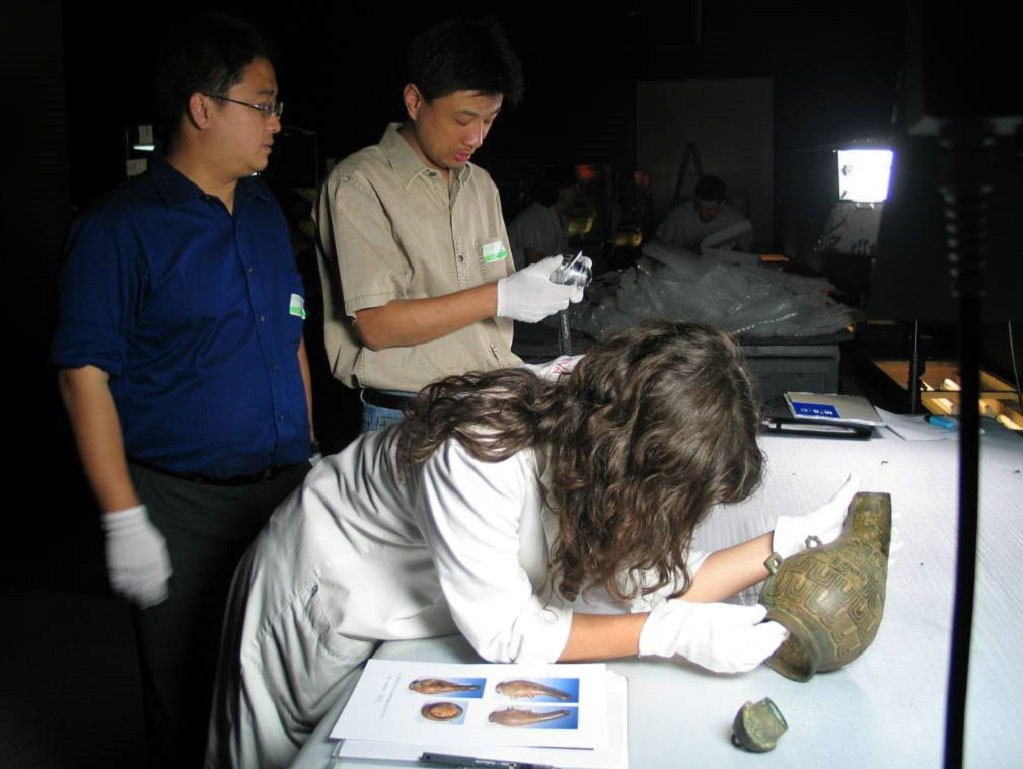

The courier work: a task often shared between the Registrars and the Curators–restorers. Photo: Maria Jesús Cabedo

Around the same time, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston established the functions of its Registry staff: to control the logistics of works, customs formalities, the management of loans and deposits, and the control of collections inventories, the photographic register and the correct storage of objects.

The standardization of protocols, a necessity

Having laid these first foundations of the profession, the need to standardize protocols and bring into line the technical processes soon became clear. The first attempt came in 1906 with the creation of the American Association of Museums (AAM), which drew up the first standardization protocols at its famous meetings in 1907. For the first 50 years, this association worked to establish standards and to introduce the rules for collections management. The first AAM ethics code, the Code of Ethics for Museum Workers, appeared in 1925.

The 1950s were crucial for the development of the standards of the profession. The discussions among collections management staff noted down at several meetings culminated with the publication in 1958 of Museum Registration Methods, the reference manual for officers in the sector. From 1968 to 2011 it was revised, updated and reissued, and it is now in its fifth edition.

The boom in this profession in the USA was due to the phenomenon of authorizations that American museums experienced in the 1960s as a result of the Belmont Report on the state of American museums, which had been commissioned by the Federal Council on the Arts and Humanities, requested by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1976.

Many American museums aspiring to receive federal funding realized that the profession needed an authorization system to reach the standard of quality in Museum Administration. This process led, first, to the standardized professionalization of registrars and curators and, second, to the rapid proliferation of different specific university degrees in Collections Management. It is enough to list a few of them to give us an idea of the dimension that the profession reached in the 1970s in America: the Cooperstown Graduate Program (from 1964), the University of Delaware’s Museum Studies Program (from 1972), the JFK University Program in San Francisco (from 1974), and the George Washington University Museum Program (from 1976). A report similar to Belmont was drafted in France some years later: the Richer Report (2003), which tackled the problem of collections management.

In Europe the first registrars and collections management experts date from the late 1970s. The first registrars that we know of in museum management systems are those of the National Gallery, which has had a Registry Department since 1977, the National Portrait Gallery, in 1978, and the Tate Gallery, in 1979.

In Spain, training in this professional profile did not appear until the late 1980s, with the arrival of renewals, enlargements and openings of new museums. The first registrar is recorded in 1986 and the first museum to introduce it was the Instituto Valenciano de Arte Moderno (IVAM), then directed by Tomás Llorens. Llorens had appointed Vicente Todolí, who had graduated in Museum Studies in the USA, to the curatorial department. Todolí created the first Registry and Collections Management Department in a Spanish museum and he invited Corinne Diserens and Elizabeth Carpenter to train the staff of the recently created Collections Department, following the methodology of the register in American museums.

Later, and due to the lack of training platforms in Spain, the Registry staff of the IVAM moved to the Registrar’s departments of the MoMA, the Whitney and the Guggenheim in New York to complete their training. The office of the Registrar had come into being in Spain, and in the organizational structure it was on the same level as the Restoration and Conservation departments.

Gradually, other Spanish museums incorporated the figure of the collections management officer: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Thyssen Bornemisza or the case of the Museo del Prado which, although it had had a Documentation Service since 1985, the office of registrar was not mentioned in its organizational structure until 1991.

In Catalonia, the profession developed in the late 1980s and it received a great boost after the 1992 Olympic Games thanks to the many temporary exhibitions that were organized and to the appearance of new museums: the Museu d’Art Contemporani (MACBA), the Centre de Cultura Contemporánea de Barcelona (CCCB), the Fundació Tàpies, la Fundació Miró or the redesigned rooms in the Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya. Although other museums already had documentation departments, they all incorporated the standards of the Registry, on some occasions as a specific Registry and Collections Management Department and, on others, combining it with exhibition coordination.

Along with the creation of new museums and institutions, the network of national, regional and local museums was set up in Catalonia. Although the institutions’ awareness of the need for these professionals has increased in line with the volume of objects loaned and the movement of artistic assets, the same cannot be said as regards their continual training or the legislation, still subject to the Llei de Museus 17/1990, of 2 November, or the Llei de Patrimoni Cultural Català 9/1993, of 30 September. There are platforms from which Registry staff can bring their standards of quality up to date. One of the most active is the European Registrars Conference, which was set up in 1998.

Old inventory files; today they’re replaced by software specialized in documentation of collections. Photo: Wikipedia

What do Registry and Collections Management mean?

There are two ways of understanding what in the English-speaking world is known as Collections Management:

- The American school, or Anglo-American, which, encompassing the tasks previously mentioned, also covers aspects related to the overall logistics of collections.

- The European school or aspect, with closer ties to the physical registration of pieces, cataloguing, documentation and the conservation of collections.

The Anglo-American model

Given the registrar’s specialization in fields like transportation, insurance or the upkeep of collections, in America the registrar works independently of the curator or conservator, and his duties revolve around a core mission: registration and keeping inventories.

This function is defined in the Code of Ethics for Registrars, drawn up in 1984 by the Registrars Committee, at the AAM, and, in Great Britain, by article 2 of the founding charter of the United Kingdom Registrars Group (UKRG) in 1992, revised in 2014. Both documents establish that this officer’s core mission is dominated by eminently logistical tasks, although duties referring to acquisitions policies and admissions management (donations, deposits, purchases, legacies, and so on) are also included.

When an object joins, the implementation of the technical file is done by the Registrar. Photo: Bark Frameworks

They are also responsible for managing loans, transportation, packaging (collaborating closely with Preventive Conservation), storage, customs formalities and insurance. They have to be specialized in risk management and logistics and one of their greatest responsibilities is the creation and management of the legal documentation of collections, guaranteeing the safety of objects, insuring their movements, organizing transportation and verifying inventories.

The European model

The European model differs from the Anglo-American one. It is characterized by the dominant figure of the heritage conservator or collections curator, who, moreover, supervises the inventorying of collections, documents them and manages lending them for exhibition projects that may request them. The collections registry department at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris was set up in 1977 according to this model, and it was subsequently copied by the Musée d’Orsay and others. Gradually, the French model of the registrar – although maintaining its strong curatorial links – has leant towards loans management and its risks, associated with the circulation of works of art and assets of patrimonial interest, and it has become specialized in two major areas of responsibility: organizing or supervising the logistics of collections in the technical, administrative and financial spheres, and assessing the risks associated with transporting cultural assets through the application of preventive conservation measures, security and insurance.

In Europe, the BIZOT group, Groupe international des organisateurs de grandes expositions, of which this museum is a member, is a discussion forum for major museum directors for standardizing and improving their loans and exhibitions management policies in Europe and the world. It has played a very important part in the definition of the registrar’s duties. Since 1992 it has promoted the standardization of professional practice.

The other European platform par excellence for the normalization and professionalization of the registrar is ICOM (International Council of Museums), which drafted a report on loans management policy that corresponds to the Council of Europe’s Resolution 13839/04 for the mobility of collections.

Currently the British and French models are at the forefront of a new concept of registrar looking after collections management. Other countries, especially Italy, Germany, Spain, Switzerland and Austria, have been updating their standards and they have adapted them to the idiosyncrasy of their countries (for example, in Italy the profession revolves around loans management – the famous Ufficio prestiti). Nowadays, the profession is focusing on a profile of an officer qualified to handle risk management, as we learn from the different reports that have been drafted since 1998 at the biennial meetings of the European Registrars Conference (ERC):

- at the Paris meeting of 2000 subjects were dealt with such as Condition Reports (reports on the condition of works), the insurance of works, the planning of storerooms, European air carriage or immunities

- at the meeting in Rome in 2002, discussion was about circulation permits for works of art in Europe, loans management of ecclesiastic patrimony and non-museum institutions, the role of the courier, security in exhibition rooms, the handling of works of art and indemnities

- At Wolfsburg in 2004 the focus was on state indemnities, unconventional packaging materials, the handling of contemporary photographs, the transportation and installation of delicate objects

- In 2006 aspects were dealt with like museum design plans, the handling and management of storerooms, the ARMICE project, collection mobility projects, loans management, customs procedures, state guarantees

- At Basel in 2008, discussion was about the documentation and storage of collections, the registration and documentation of works on new supports, ethical and legal aspects of the profession, standards of procedures and circuits

- At Amsterdam in 2010, the focus was on the economy of means and the ecology of materials

- The meeting in Edinburgh two years later was focused on how to maximize collections and the optimization of circuits in loans management

- The latest meeting, in Helsinki in 2014, dealt with aspects like security, the tasks of the courier in the 2.0 age, risk assessment in loans, cases of robbery and the recovery of patrimony, insurance, collections in movement and tools of the profession in the future.

Towards an emerging profession

From the working dynamics of the different platforms of professionalization that we have described, one learns of the trend in recent years towards the centralization of the registrar’s duties in three major categories or competences: technology, scientific and administrative. The current figure of the registrar, in both Europe and in the English-speaking world, requires multidisciplinary knowledge and great versatility. It is a highly qualified professional profile that shares a professional curriculum with curators and with conservator-restorers.

As Delsault-Lardy and Vassal pointed out, in “Acteurs et compétences” (2000), “registrars and curator-conservators must work together […] and share the responsibility with respect to data gathering on works and their accessibility.” In fact, this professional pairing has already become a general rule in Europe. The world of contemporary art is a clear example of the need for this pairing of the registrar and the curator. As Yvan Clouteau points out, the conservation conditions of modern works necessarily require shared knowledge in various fields, principally those of conservation, documentation, restoration and museum organization. Today the work of the registrar cannot be understood without the concept of task sharing as an organizational tool of all institutions with patrimonial responsibility.

With respect to the legal-administrative aspect of the professional profiles of the registrar, it should be pointed out that in the public institutions handling large-scale collections (national museums or collections of more than 10,000 works) the ratio of registrars to the number of items in the collections must be a figure directly proportional to the annual volume of loans, deposits, donations, acquisitions, and to the number of sub-collections or sub-specialities that its collections contain. Museums with large collections these days have registrar’s departments with between five and ten officers (Centre G. Pompidou, Metropolitan Museum and others).

As to the professional profile, the demands of collections logistics mean that nowadays registry departments are flexible and cover different stages in collections management, whereby they are increasingly adopting pyramidal structures composed of a senior registrar and a variable number of registrars and assistant registrars.

Don’t miss the second part of this post, “The Registrar in Collections Management: Risk Management,” which will be published shortly.

Related links

STOLOW, N, Procedures and conservation standards for museum collections in transit and on exhibition, pdf

Registre d’obres d’art i Gestió de Col·leccions