Joan Yeguas

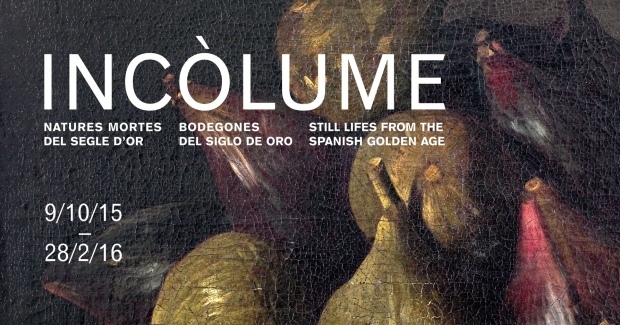

Mounting an exhibition is a complex thing, because it involves different people working towards a common goal. In this one, Undamaged. Still Lifes from the Spanish Golden Age, I have acted as the chief curator, one more of the team working together. I do not wish to talk about a curator’s duties, because I would have enough material with which to write a doctoral thesis, and because not all exhibitions depend on the same factors. However, I can tell you about my experience behind the scenes.

The chief curator generally searches for, selects and rules out the works of art that are going to be in the exhibition catalogue. On this occasion, there was no selection, because it was a case of exhibiting a group that had already been determined. They are 19 paintings that an anonymous collector has ceded to the museum for a period of five years. The unusual thing is that all the works are Still-lifes done by Spanish artists between the years 1615 and 1670.

Documentary research

And so, the works to be studied having been defined, we grouped them into 15 entries: 13 individual works and two groups. Then a process of art history research began, a task that we curators are used to doing. For this, I had the inestimable help of museum curator Francesc Quílez. This task consists of looking for literature, books and articles, that refer directly and indirectly to the paintings, with the aim of contextualizing the artistic phenomenon. There was very little literature dealing directly with the works in question, but it had to be read. By indirect literature we mean that related to Spanish painting of the seventeenth century, specializing particularly in still-lifes and vases of flowers. It would have also been useful to have other information about the works – a contract or payments, the original location, the patron, and others – but this is almost impossible in paintings that appear with no sales history on the art market.

Analysis of the works

When the paintings arrived at the museum another stage began, that of obtaining data using apparatus: X-rays, infrared reflectography, viewing the pigments under the microscope, and so on. This examination and analysis made it possible to extract a series of essential clues about the supports and the painting techniques, and to see what these works had suffered over the years, something very common when they originate in the art trade.

Apart from this information, quite limited when searching for authorships, the art historian can always resort to a traditional and fundamental technique, which to date still sustains many of the existing attributions around the world, and which has undoubtedly helped historiography to progress: the observation and analysis of the work of art with the naked eye, provided the eye is trained and performs a role of stylistic comprehension.

Authorships and attributions

It was necessary to write the entries for the catalogue that we have published, and which has served as the basis for the labels the visitors read in the galleries. Some of these entries were easier, because we were starting from known works with their own reference literature: three works by Juan van der Hamen, the Antonio Ponce, the Master of Stirling-Maxwell, the Juan de Espinosa, the individual Tomás Hiepes and the group one.

The rest of the paintings were completely unpublished. Some were signed and corresponded to the style of the painter in question: the group of vases by Pedro de Camprobín or the Juan de Arellano. An authorship has been proposed for the other five, but there was no previous literature, they were not signed, there was no other data that might be of use. Therefore, stylistic comparison was used: the Juan van der Hamen with the basket, the Agustín Logón, the Master of the written Vanitas, the plate of figs by Pedro de Camprobín and the one we have circumscribed to the circle of Francisco de Zurbarán.

It could be said that I was responsible for the content. But an exhibition has to be displayed properly to the public and it has to be publicized. Behind all this, there is the work of different areas and departments of the museum: restoration and preventive conservation, exhibition management, movement of works of art and museography, publications, communications, digital media, press and others that I shall not mention, in order to keep this short, as well as the work of external collaborators, such as the graphic designer, translators, and so on. After the opening, this joint effort is put to the test. It is up to the public to judge and enjoy.

Related links

Bibliographic research in the library of the museum

Art del Renaixement i Barroc