Anna Carreras i Àngels Comella

The Frontal of sant Pere de Boí as it is conserved today.

It is difficult to imagine, nowadays what a classical or medieval work of art looked like when it had just been finished. You only need to think about the controversy caused by the cleaning of the paintings of the Sistine Chapel, which allowed us to see the colours themselves of the painting by Michelangelo, or the surprise at seeing a Parthenon, a Venus de Milo or a Romanesque cloister with all their original polychromes.

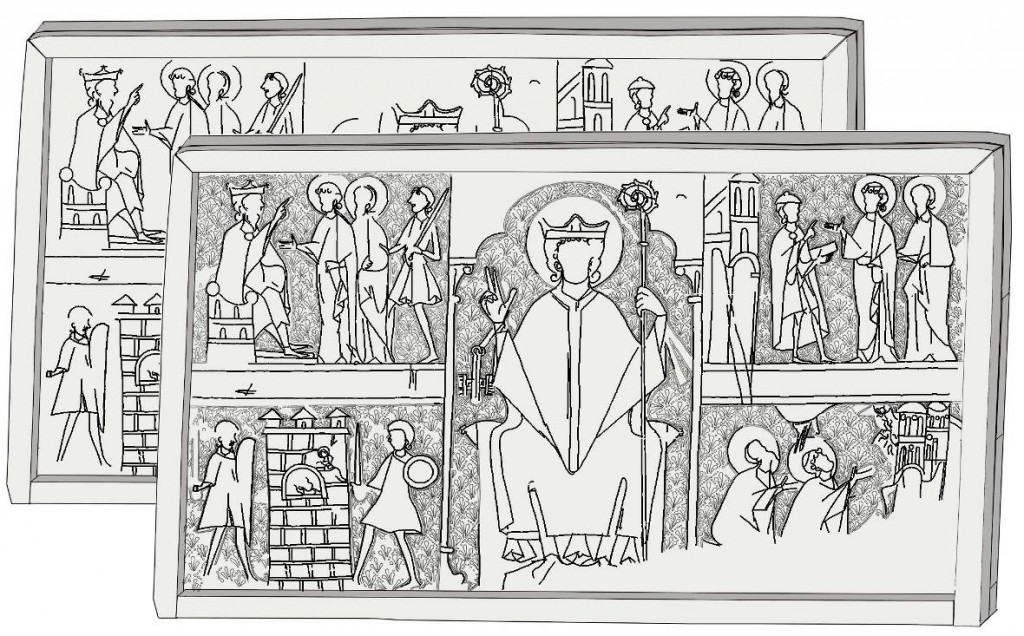

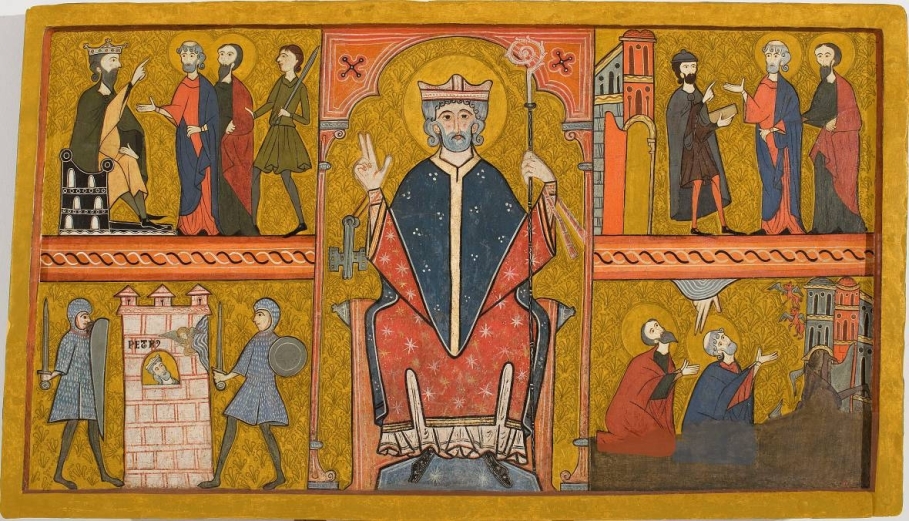

An example of this is the Frontal of sant Pere de Boí from the workshop of La Ribagorça from the mid-13th century, that forms part of the Romanesque Art Collection of the museum. The central image represents Saint Peter as a bishop, with a staff and mitre, surrounded by four scenes of the life of the saint. This work currently offers a very different image to the one it originally had.

Preserving, conservating and studying works of art are the most important tasks of the conservator-restorer. Over the years, the aging and the transformation of the constitutive materials of the work, the environmental conditions, and the human touch by people’s hands are factors that can cause, in some cases, alterations that lead to an understanding of the work which is not true to the origin, thus creating erroneous interpretations over time.

For us, the scientific studies (infrared reflectography, ultraviolet light, X-rays and the analysis of pigments) are fundamental tools for making a deep analysis and for correcting these unfortunate interpretations of the past.

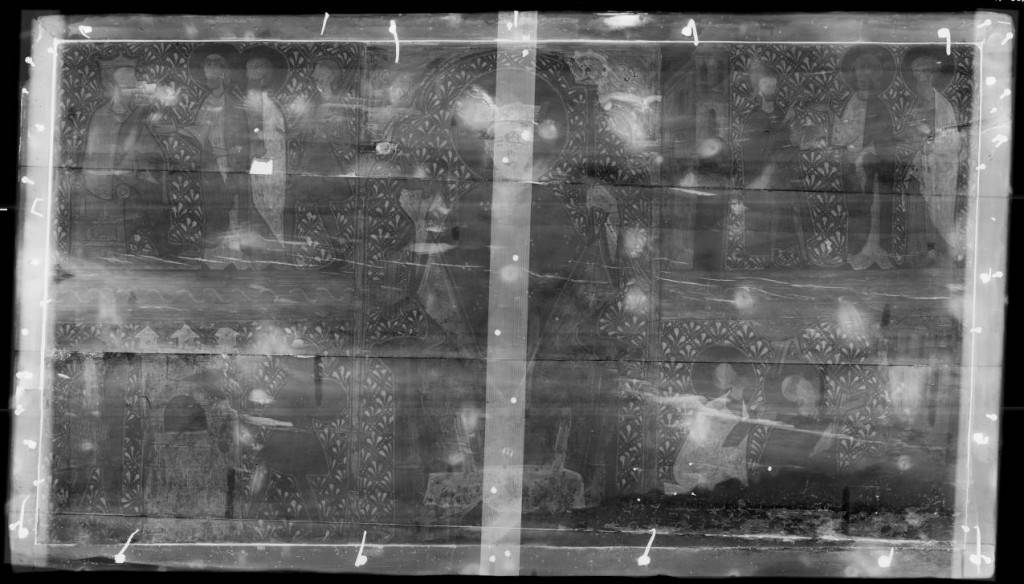

In this case, the radiographic image was the fundamental tool for knowing, to the minimum detail, the constructive aspects of the work, and those which couldn’t be perceived in any other way.

What was the creation process of the support?

■ Analysis of the support

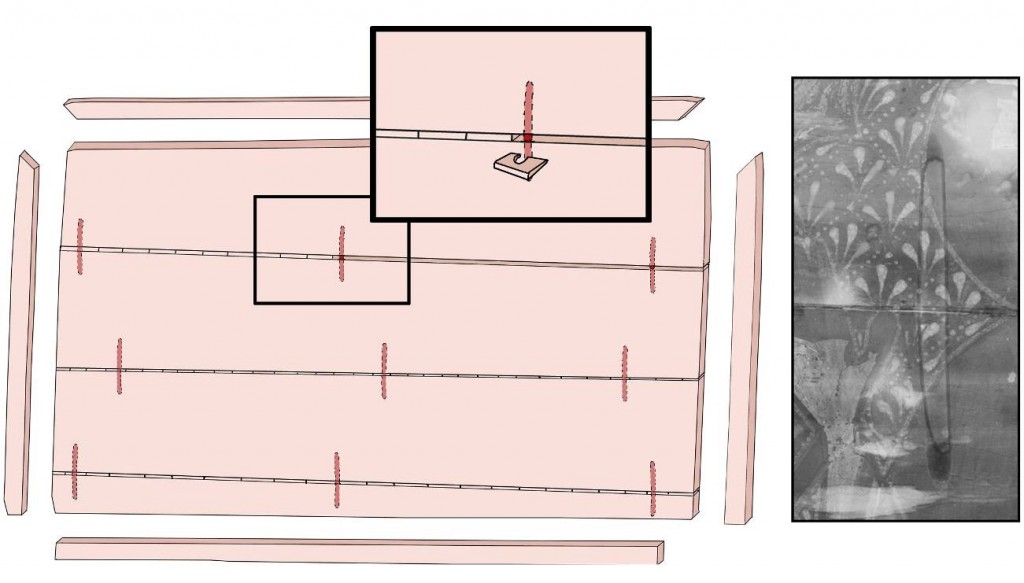

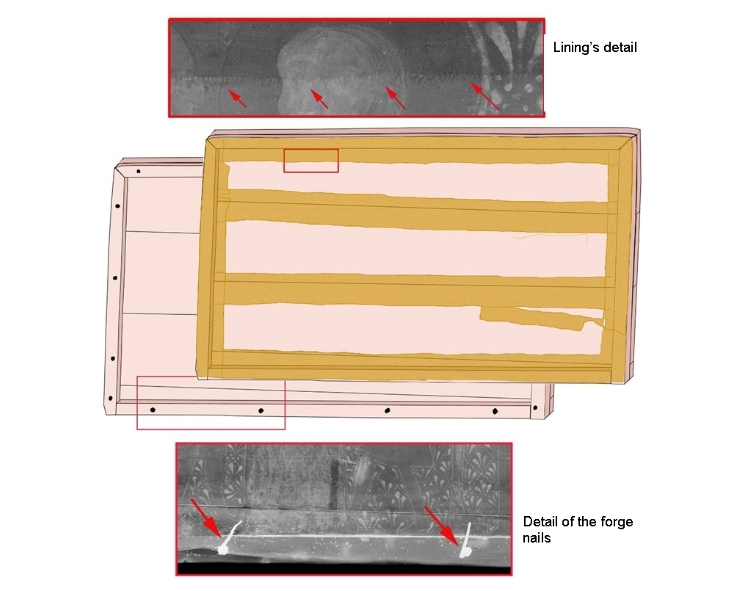

Observing the radiographic image we see that the altar piece is formed by four horizontal wood panels, joined by some internal dowel. Small slats of wood were detected, called capiamples, that fitted in with the line joining the panels, and served as an expansion joint of the support. Subsequently four cross-pieces were fixed with forge nails that functioned as a frame.

Another visible element with X-rays and that also belongs to the moment of the construction of the panel are fragments of cloth stuck to the joints of the union between the panels and the cross-pieces, prior to applying the preparation layers. This procedure, that the restorers call clothing, had the aim of homogenising the surface and strengthening the joints of the different wooden elements for preserving them from subsequent movements.

The image of the forge nails in the perimeter of the frame that confirms that it is original. The nails, highlighted in red, can be found under the lining.

■ Analysis of the pictorial layer

Subsequently on the lining, various preparatory layers were applied elaborated with animal glue and plaster on which, afterwards, the incisions were made. Until this point, it could be considered that the construction of the support of the work had been finished, and now began the more creative phase of the artist.

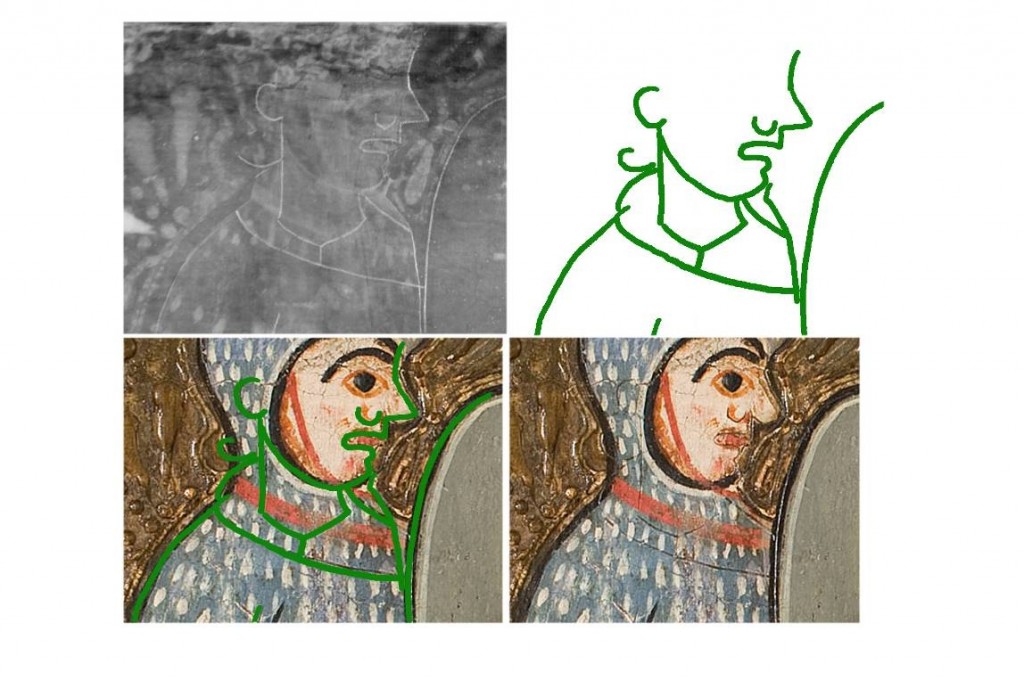

The incisions correspond to the preparatory drawing that served to help to fit in the distribution of the different scenes. This was done with a sharp and pointed utensil which worked directly on the preparation layer.

Once the drawing by incision was complete, the decorative phase of the application of stucco relief began, very diluted with a brush or with a pastry piping bag.

Once the drawing by incision was complete, the decorative phase of the application of stucco relief began, very diluted with a brush or with a pastry piping bag.

The chemical analyses confirm the presence of the remains of tin on these stucco relief. What did they mean? What was the tin doing here?

In the 13th century, in the moment that the polychrome was applied on the frontal, both the artist and the client were interested in it seeming to be a piece of furniture with gold-work, in which it was important that the gold, a symbol of wealth, was present.

How did they manage to get the gold to shine? They applied sheets of metal on top of the stucco relief that was subsequently stained with a yellowy varnish. This process was called gilding.

Over the years, we often find that, the tin sheet becomes oxidated, becomes blackened, and ends up disintegrating or disappearing, which irreversibly transforms the original image of the work.

Can you imagine how the citizens of the time saw the frontal?

The background with gilding tin of the Frontal of sant Pere de Boí have deteriorated to such an extent that it had a golden aspect, and still now, it is dark and brown. With the use of a computer program for image treatment, it has been possible for us to make an approximate virtual reproduction of how the work would originally have been. This new image with the golden background surprises and contrasts with what we have been used to seeing in pieces from this period.

The confluence of the scientific studies, of the chemical analyses, of the application of computer systems and of the capacity to interpret of the conservator-restorer have made it possible for the studies of the pieces of our heritage to be more and more rigorous and extensive. The study of this case is within the framework of a research project that we are carrying out about the series of frontals of the Workshop of Ribagorça.

Anna Carreras and

Conservació-restauració