Ricard Bru

In the summer of 2018, the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando in Madrid organised, together with the Fundación Japón, an exhibition dedicated to supernatural Japanese beings known as yōkai. Entitled Yōkai: iconografía de lo fantástico, Yokai: Iconography of the Fantastical, the show exhibited, for the first time in Spain, pieces chosen from the large collection given recently by Yumoto Koichi to the city of Miyoshi. To coincide with this exhibition, the organisers asked to hold a conference on the impact of the Japanese supernatural imaginary on Western art in 1900, and it was then that, once initial prospecting was completed, more and more examples began to appear in the Museu Nacional’s collections of this peculiar and little known aspect of the attraction held by Japanese culture. It is an aspect of Japonism that can, nevertheless, prove to be fascinating.

From 2014, the modern art exhibition rooms of the Museu Nacional have included a specific space dedicated to Japonism which, in a synoptic way, displays some representative examples of how, in line with a tendency shared throughout Europe and the United States, the discovery of Japanese art became a transformative driving force for art in Catalonia and energised the modernisation of some artistic practices in need of a breath of fresh air. The pair of oil paintings Before the Ball and After the Ball by Francesc Masriera and the picture Woman with a Kimono in Profile by Eduardo Chicarro, form part of the selection of the museum’s works associated with Japonism.

However, the impact of Japanese art on Catalonia, as in the rest of the Western World, transcended the field of Fine Arts from the very first moment and extended into society as a whole. Japonism permeated daily life in different and often non-obvious ways at the turn of the century and did so across all kinds of industries related to the art world, from glass and ceramic workshops to furniture makers and textile companies. The museum collections reflect this tendency as well. In fact, Japonism also reached as far as the worlds of photography, music, theatre, literature and poetry. This is the way in which, in Catalonia, Japanese art became a source of fully fruitful inspiration and a model that went far beyond copies of warriors, cranes and cherry trees to the point of getting into the more grotesque and surprising imaginary of Japan’s tradition of the fantastical.

The arrival of the yōkai to the museum

From the 1850s onwards, once Japan was forced to open up its ports, the access of Westerners to the archipelago made it possible for many aspects of its art and culture to come to light. There are various accounts by diplomats, travellers and traders who, within a few years, started to describe and acquire supernatural artistic scenes; ‘horrifying, fantastical and diabolical drawings’, as Aimé Humbert wrote in 1863. Very soon, an enormous volume of fantastical images began to arrive in Europe, either concealed within the pages of illustrated books or as individual prints and ‘objets d’art’. So much so that, in 1868, Ernest Chesneau had no hesitation in highlighting these grotesque images as an idiosyncratic feature of the country’s artistic tradition: ‘all of the human race’s deformities appear successively, and to these real deformities are added an infinite number of imaginary deformities’. It is no surprise then, that once the Meiji Government came to power, the growing enthusiasm for Japanese art, along with its widespread diffusion, led to many of these works ending up in the hands of artists and collectors such as Edmond de Goncourt, Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Monet and Charles Haviland. They, and many others, are examples of the easy access Europe had to the fantastical iconography that emerged from the famous illustrated scrolls Hyakki yagyō emaki and the hundreds of images created during the 18th and 19th centuries by artists such as Katsushika Hokusai and Kawanabe Kyōsai.

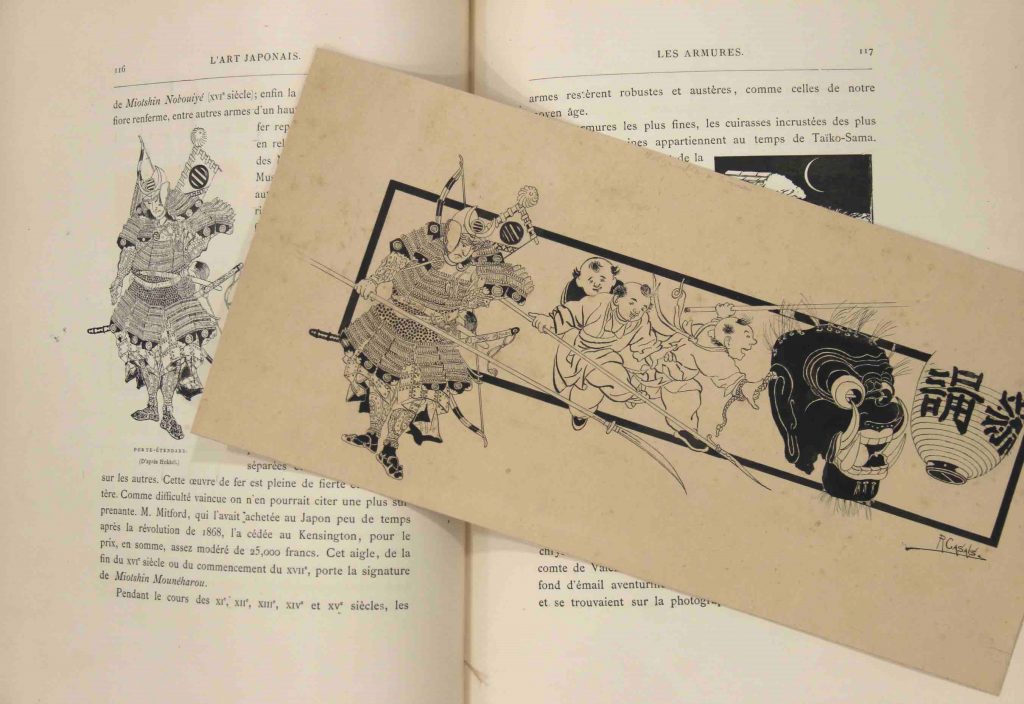

Anyone visiting the Museu Nacional who want to confirm for themselves the existence of this fantastical Japonism just needs to take a glance at the books and magazines in the library, especially those that have come from old Junta de Museus library and historical collections such as that of Alexandre de Riquer. Thus, the images of me-hitotsu-bō (one-eyed beings), rokuro-kubi (beings whose necks can extend and rotate) and Ōkubi (beings with giant heads), along with other monsters and ghosts based on Japanese tradition, appear on the pages of books such as L’art japonais (1883), Ornements du Japon (1883) and Le Japon Artistique. A number of illustrations from the Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats del Museu (Drawings, prints and posters) reveal the extent to which these books became a point of reference and model for Catalan artists at the turn of the century such as Ramon Casals Vernis.

Japanese themed drawing by Ramon Casals based on fragments of illustrations in the second volume of L’art japonais (1883) by Louis Gonse. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Barcelona.

Catalonia also welcomed the stories and legends arriving from Japan with open arms. This was made possible particularly thanks to the warm reception of Hasegawa Takejirō’s publishing project, aimed at disseminating traditional Japanese stories through beautifully illustrated publications, initially in French and then in English between 1885 and 1889 (Japanese Fairy Tales and Les contes du Vieux Japon). These small format books, printed in colour on chirimen paper, were bought by artists such as Josep Lluís Pellicer, Oleguer Junyent, Joan Vila d’Ivori, Víctor Oliva, Frederic Marès and Apel·les Mestres and attracted interest not only for the tales they told but also the illustrations, commissioned to painters such as Kobayashi Eitaku.

Their pages tell stories such as The Old Man and the Devils, featuring a huge group of the most bizarre of beings, or The Tongue-Cut Sparrow, involving the terrifying appearance of a squirming horde of diabolical slug and toad-like creatures. These were so well received that their popularisation was massive and some of the stories such as the Urashima, the Fisher Boy and The Mirror of Matsuyama, were republished more than a dozen times in magazines and newspapers of the time including La Ilustración Artística, La Esquella de la Torratxa, El Camarada, La Dinastía, El Liberal, Barcelona Cómica, El Gato Negro, Iris, Pluma y Lápiz, El Noticiero Universal, La Vanguardia and Cu-Cut. As an example, a story based on the Hasegawa series entitled The Serpent with Eight Heads appeared in modernist journals such as Hispània, The Old Man and the Devils appeared in story anthologies by L’Avenç, while the Tongue-Cut Sparrow was published in magazines such as Pèl & Ploma by Ramon Casas and Miquel Utrillo. It is no surprise that their illustrations appeared in story collections such as The Thursday Fairy Tale, and that they formed the basis for other short stories such as Deceiving the Demons, illustrated in 1924 by Joan Vila d’Ivori.

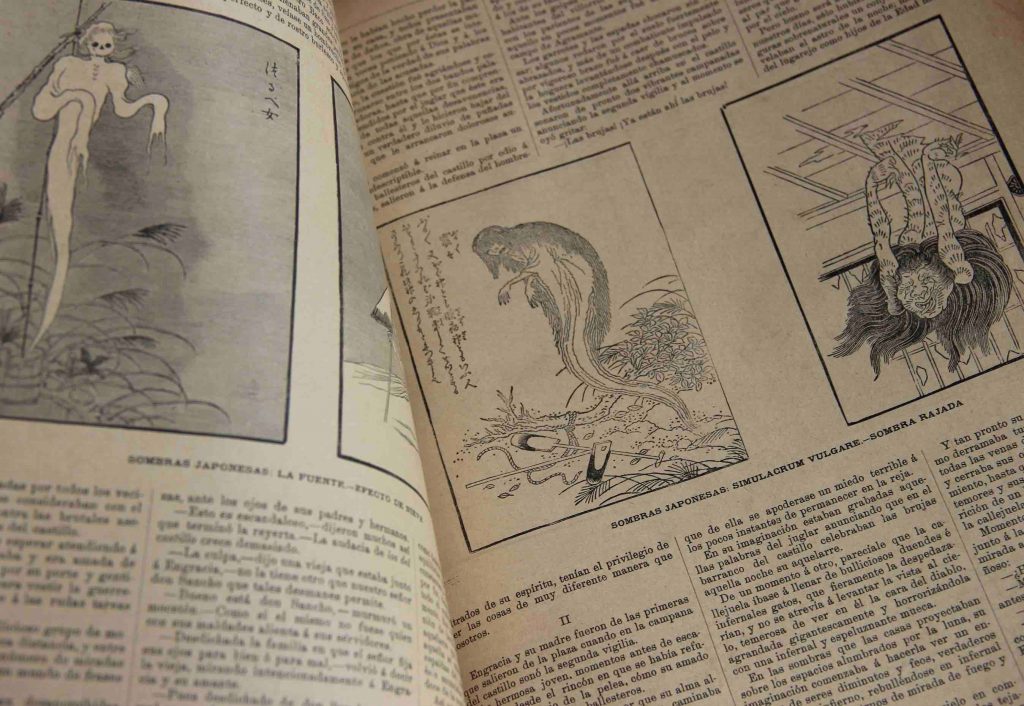

Notes such as those published in La Ilustración Ibérica of 27 November 1886, which reproduced various illustrated pages from the leading 18th century Japanese yōkai manuals, show with certainty that the fantastical world of Japan entered the imaginary of the Western world in the late 19th century. In this respect, writers such as Siegfried Wichmann and Samantha Sue Christina Rowe have already studied the impact of Japan’s fantastical imaginary on European art in 1900, especially in the sphere of symbolism and the work of artists such as Beardsley, Redon, Gauguin and Ensor.

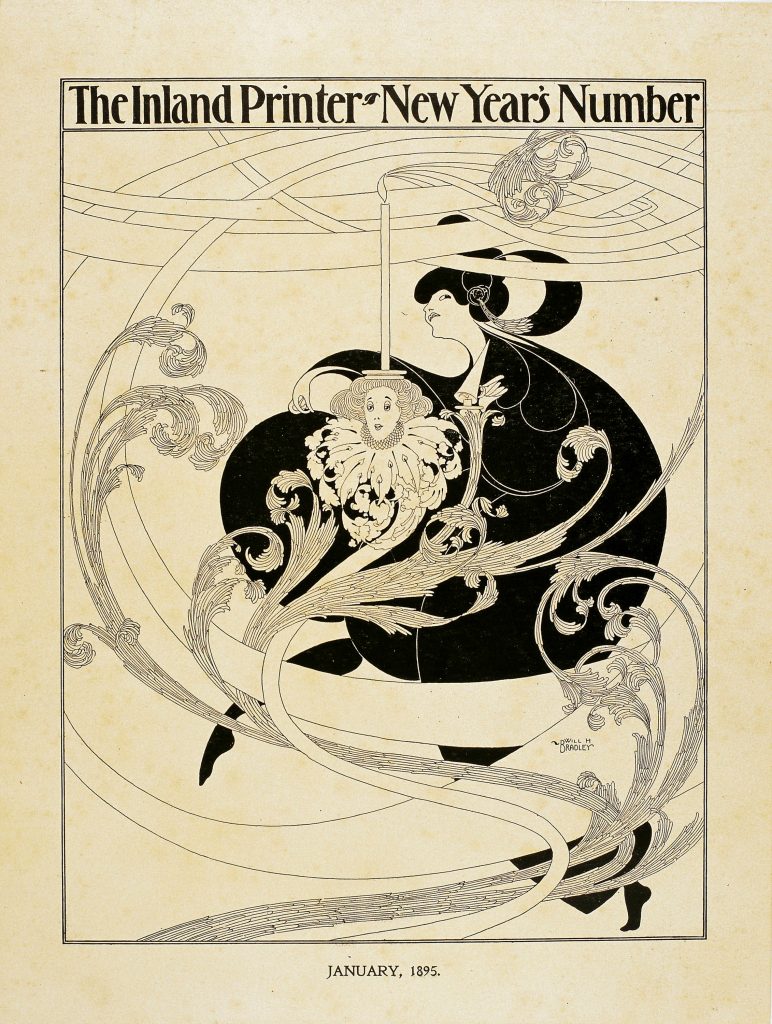

The illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley, a fervent collector of Japanese illustrated books and erotic prints, are an example of the way in which the imaginary of the yōkai became rooted in artists who were part of the symbolism and decadence movements. Despite his unexpected death at 25 years old, Beardsley’s short career left behind modern and revolutionary works such as the illustrations for the small book entitled Bon-Mots. The copy kept by the museum, which comes from the old library of Alexandre de Riquer, shows a whole series of Japanese-inspired grotesque figures, such as the elastic and fluctuating beings, the rokuro-kubi, and others that emerged from illustrated books like the ones by Sekien and Hokusai. Beardsley, just like Guérard, Toulouse-Lautrec and other contemporaries, discovered a thousand and one deformities and oddities in the prints and illustrated books of the Edu era. Other works in the museum’s collection that are similar to Beardsley’s, such as the poster entitled The Inland Printer , by the North American illustrator William H. Bradley, can also be related to the ghostly images and long-necked beings made popular by Hokusai manga and other Japanese books.

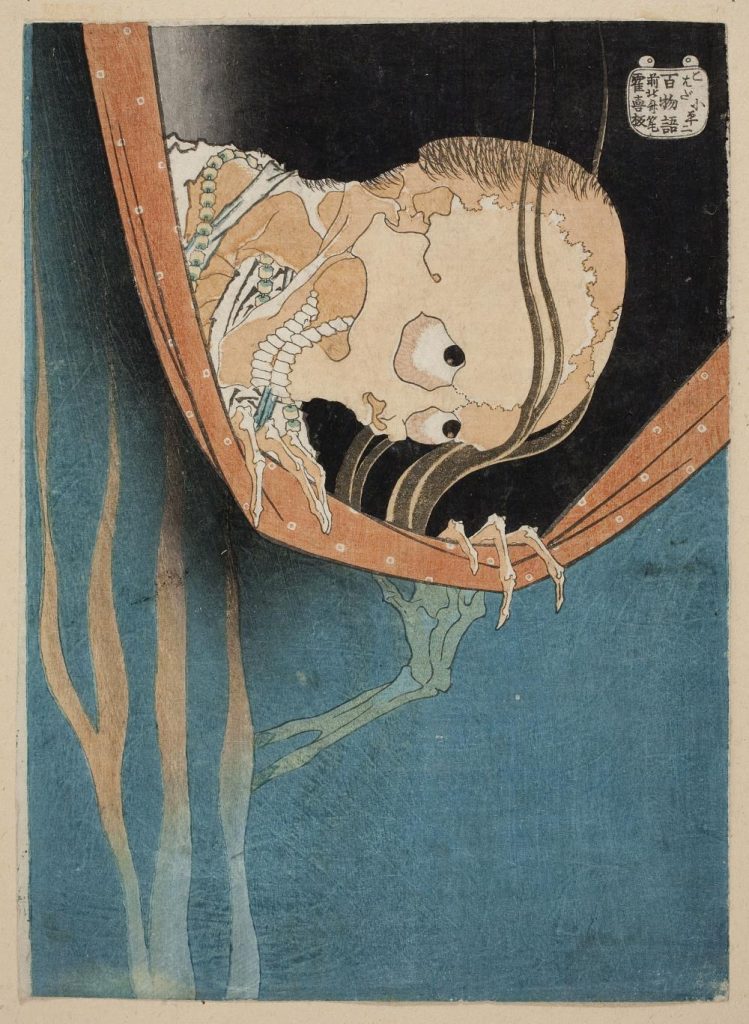

At the same time, it could be argued that symbolist painters such as Ensor, Redon and Gauguin, took a similar approach: works such as the Warai Hannya print by Hokusai, which comes from the old Ismael Smith collection, recalls the interest of Paul Gauguin’s Self-Portrait from 1889, while the image of Le cyclope (c. 1914), by Odilon Redon, is reminiscent of the popular representations of the ghost Kasane. The world of the yōkai, with all of its associated originality and creativity, transcended borders and attracted many more artists, some of whom remain to be rediscovered, such as Sidney Sime and Lyon Léopold Chauveau.

The Catalan artists: a local example of a global phenomenon

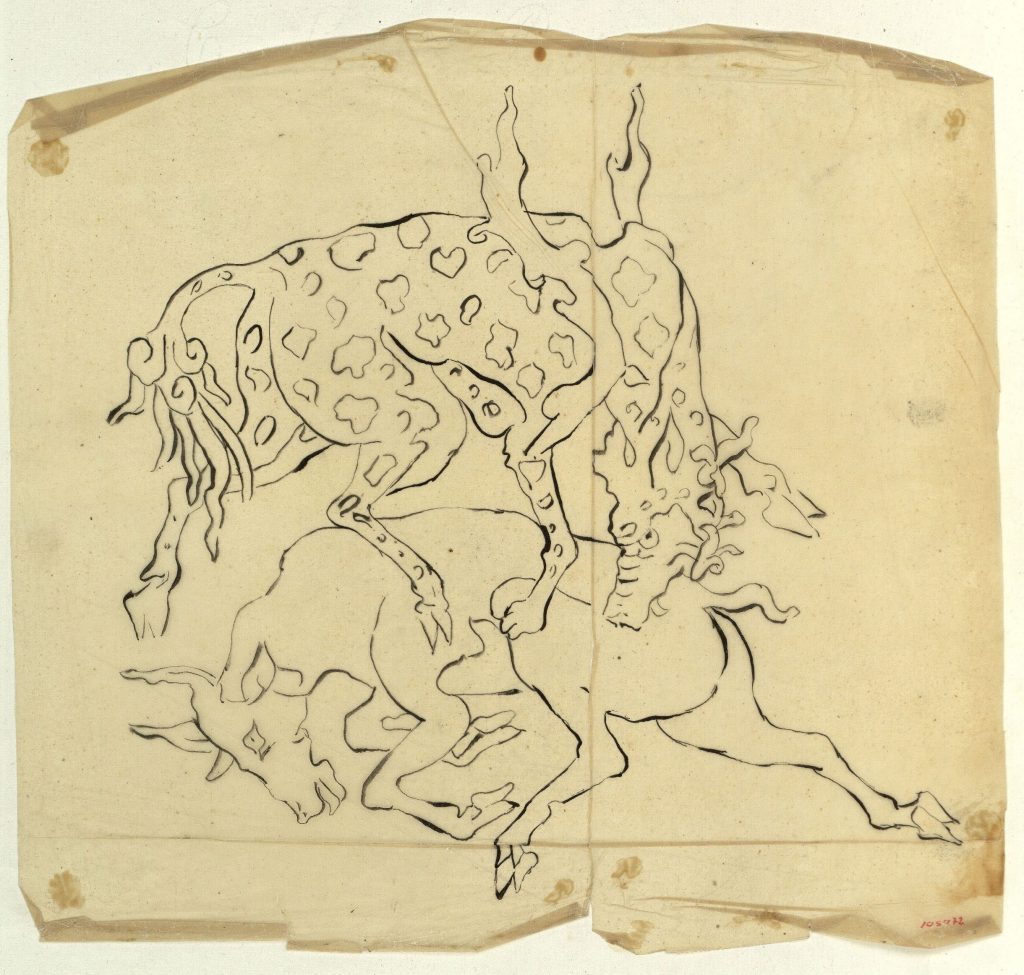

From the 1860s onwards, volumes 10, 11 and 12 of the Manga by Katsushika Hokusai proved to be an important source of inspiration for many artists in search of the fantastical, and the presence of this work in the hands of painters such as Manet, Degas and Gauguin, to name but a few, could be seen as sufficient enough proof to demonstrate the ease with which the world of the yōkai and the phantoms spread throughout the continent. In this respect, Barcelona and Catalan provide ample testimony to the spread of this imaginary and confirm the realisation that fantastical Japonism had a far greater impact than we may first have thought. In an international context, Marià Fortuny was one of the first Catalan artists to acquire and study the pages of the Manga and other similar illustrated books, concentrating as much on the natural details as the fantastical beings. Some of Fortuny’s drawings, kept in the Gabinet de Dibuixos i Gravats of the museum, show everything from fragments of giant eels to tengu and zeshōmeppō from the Manga, as well as fantastical animals such as kirin, at the heart of a series of tracings that probably served as preparatory studies for the watercolour The Tapestry Seller (1870).

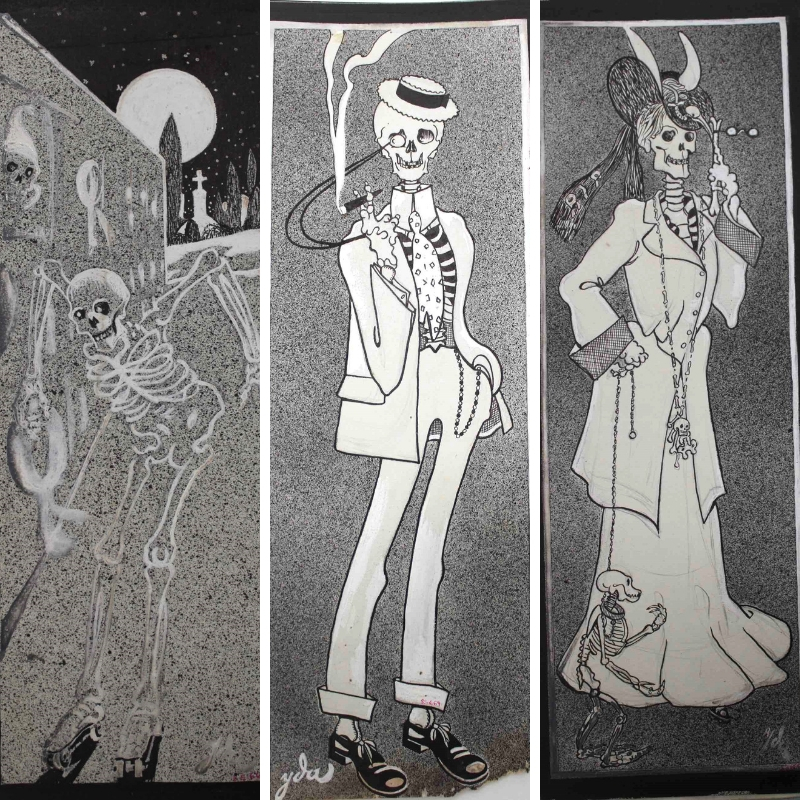

Following in the wake of Fortuny, within a few years many illustrated Japanese books entered the private collections of people like Alexandre de Riquer, Apel·les Mestres and Anglada Camarasa, Domènech i Montaner, Francesc Vidal and Frederic Marés, which, added to other collections such as those of Richard Lindau, Joaquim Mir, Josep Mansana, Ismael Smith and Joan Vila, meant that monsters, mythological beings, ghosts and spirits from Japan began to become evident in the imagination of artists. Ultimately, the extent of this diffusion facilitated the consideration of certain thematic similarities and iconographic interpretations in the work of Catalan artists. As an example, out of the one thousand plus drawings by Ynglada held in the Museu Nacional, the element that stands out is the presence of various living skeletons from 1904 that are similar to Koheiji d’Hokusai’s Ghost of Kohada.

Ynglada, known for his passion the art of Eastern Asia, would definitely have known the two prints of ghosts by Hokusai kept in the museum as they come from the collection of Ismael Smith, a friend of Ynglada’s from the times of El Guayaba who he first met at the Sala Parés in 1906. With this in mind, it is not surprising to find that, among his illustrations drawn during the first decade of the 20th century, there are scenes with singular images such as the representation of living tsukumogami objects as a parody on the Russo-Japanese War.

Any of us devoted to the history of art have been able to verify on many occasions the extraordinary value of the collections held in Biblioteca Joaquim Folch i Torres and the

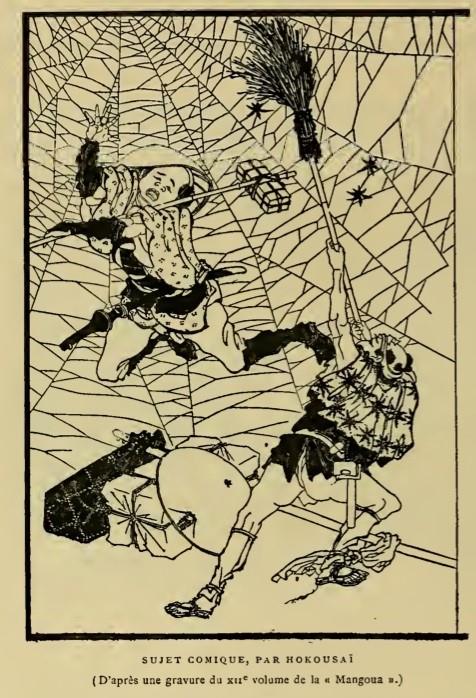

Cabinet of Drawings, prints and posters. Their richness and extensiveness conceals surprises and treasures and, as a result, a simple consultation can provide the opportunity of finding other examples of synergies between Japonism and Modernism, which is also the case for the fantastical imaginary. Apel·les Mestres, the collection of illustrated Japanese books kept in the museum’s library, is a good example of this with illustrations by Liliana; drawings such as The Spider’s Web hark back to illustrations like those in Volume 12 of the Manga by Hokusai, which was widely disseminated and reproduced at the time.

Apel·les Mestres.

The Spider’s Web. Illustration for Apel·les Mestres’ poem ‘Liliana’. 1905

Vol.12 of the Hokusai Manga reproduced in L’art japonais (1883) by Louis Gonse. Museu Nacional d’Art de Catalunya, Library

To sum up, this and other examples show how Japonism in Catalonia also left its mark on the fantastical imaginary, both around the time of 1900 and over the following decades. Research, however, has only just begun.

Related links

Japonism and its presence in the Museum Library

The Ukiyo-e of the Museu Nacional