The exhibition William Morris and the Arts & Crafts Movement in Great Britain, which opens today, is a good opportunity to take a detailed look at a far-reaching cultural episode, captivating and dreamlike, which made its influence felt in Barcelona:

Dream

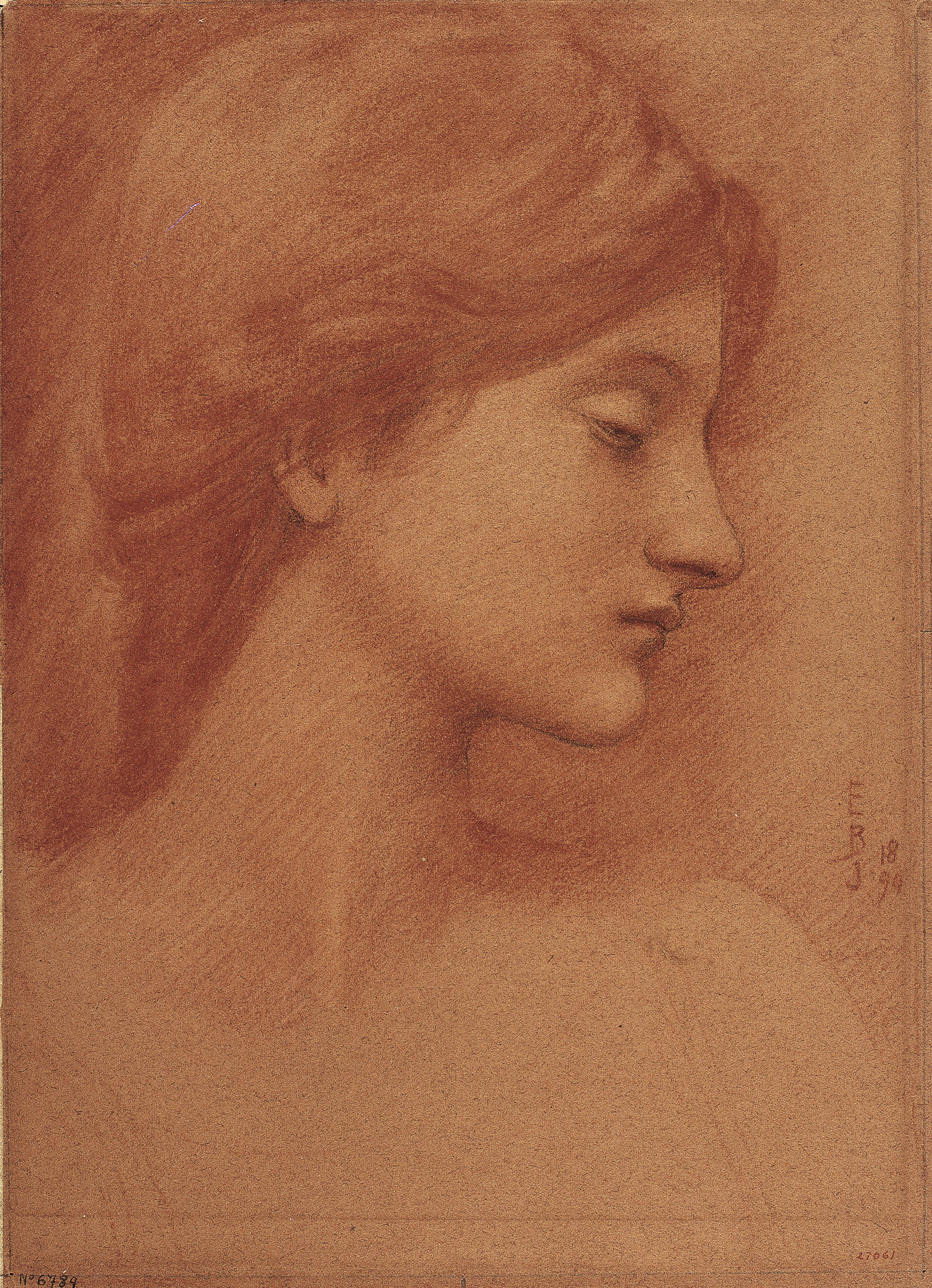

The portrait of William Morris’s wife inspired a dream in the critic J.E Cirlot, who considered her to be a prodigious embodiment of the beauty of Victorian England. Moreover, before the portrait of Elizabeth Siddal as Beata Beatrix, he felt like kneeling.

P.R.B_Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

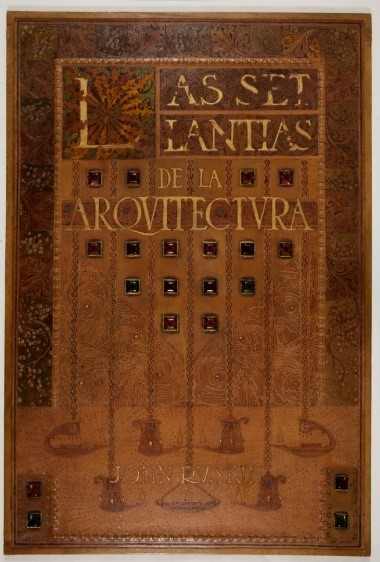

Despite the fantasies that the canvases by this group of iconoclastic Victorian artists might arouse, who challenged the aesthetic conventions of the Royal Academy in London in 1849, the truth is that they were met with very hostile reviews, as the Barcelona newspaper La Vanguardia recalled. At the International Exhibition in Paris in 1855 they were referred to as a sect: “They were like mushrooms, there was no trace of the English tradition of Reynolds, Lawrence, Constable or Turner.” They mysteriously signed “P.R.B” and it later emerged that these initials stood for Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Their ideologue was the writer and critic John Ruskin, known as the “apostle of beauty”, who instilled the moralizing idea of art in these artists.

Reflections

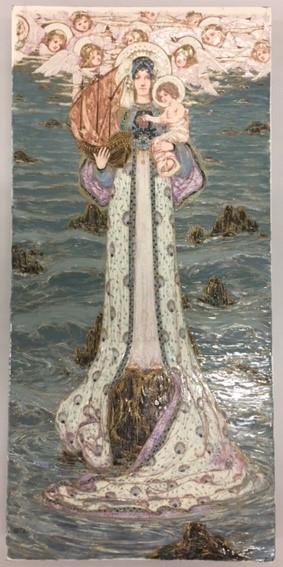

In the 1890s the influence of the Pre-Raphaelites spread all over the continent, mixed with Franco-Belgian symbolism, and influenced the visual and decorative arts. The paintings of those English artists, which invoked the Middle Ages, episodes from the Bible or Arthurian legends, were admired by, among others, Julio Romero de Torres, Miquel Viladrich and Eduardo Chicharro, some of whom even spent periods of time in Great Britain to study the legacy of the Pre-Raphaelites. Santiago Rusiñol also evoked the purity of the early Italian painters with formats inspired by old altarpieces.

Chicharro, Eduardo, The Poem of Armida and Reinaldo, 1904. MNCARS

Unfavourable reactions

John Ruskin and William Morris were especially popular after their deaths. Readers complained that buying a book by Ruskin was a financial sacrifice due to the high price, bearing in mind, moreover, the unintelligible titles and his fanciful ideas.

What’s more, the multifaceted William Morris (designer, artist, poet, political activist, ecologist, conservationist, socialist) was interpreted in a variety of different ways, sometimes rather unfavourable: Eugeni d’Ors’ Catalan translation of his utopian novel News from Nowhere (1890) cost him his job: it was considered immoral because of its apologia for free love.

The Studio, a fascinating magazine

As a destination, England was not a priority for Catalan artists. At Els Quatre Gats the drawings by Steinlen published in the magazine Gil Blas were very much admired. Ramon Casas followed Whistler, one of the public enemies of John Ruskin, whom he took to court.

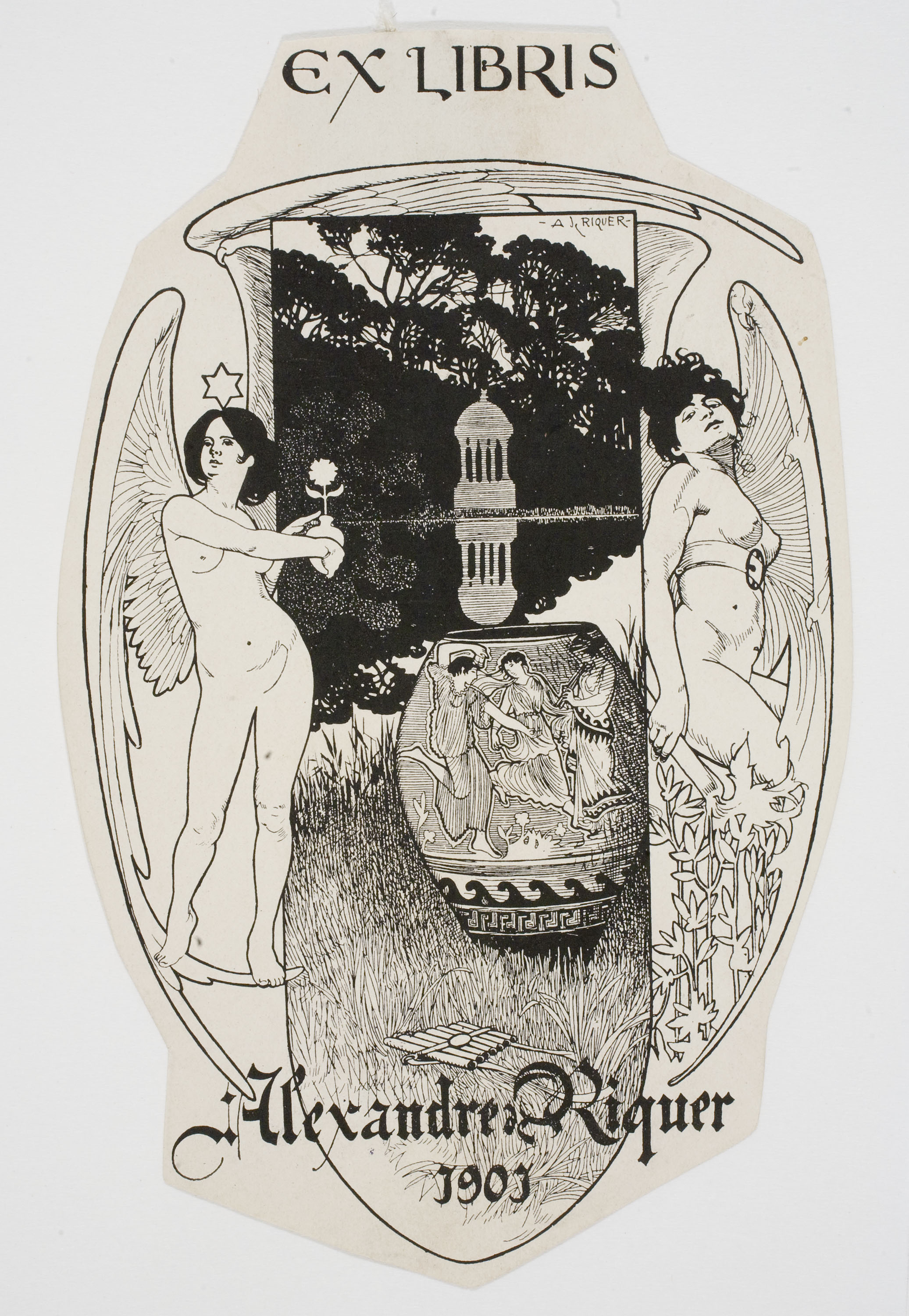

But… things changed one day when an English magazine arrived that fascinated an entire generation of designers and decorators: The Studio. Alexandre de Riquer, an ambassador of British artistic culture as a result of his stays in the country, was carrying it under his arm. A new devotion to England was awakened that also took root in Rafael Masó’s Girona.

The Barcelona International Exhibition of 1907

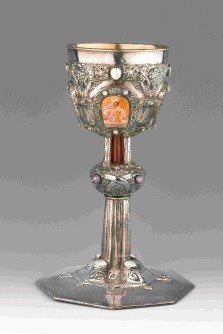

A milestone in Barcelona for first-hand knowledge of British art was the International Exhibition of 1907. The poet-artist-craftsman Alexandre de Riquer was the curator of the English section and he managed the loaning of works and some purchases bound for the Museu Nacional, such as the creations of Edward Burne-Jones, Rackham, A. Woodward, Brangwyn, León Solon, or the Arts and Crafts designer and enameller Alexander Fisher. These enamels encouraged Marià Andreu to set a Guinness record: making a gigantic enamel.

The spirit of Morris and the Arts and Crafts had also reached the various workshops of ceramicists, stained glass makers and cabinetmakers, who were working under the wings of architects in Modernista Barcelona. It was a moment of splendour that did not go unnoticed by the English author of Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh, who was fascinated by the ceramic covering on the front of Gaudí’s Casa Batlló.

Continuum

Pugin, Ruskin and Morris extolled the beauty and sincerity of the period of the cathedrals, and they considered that manual craftsmanship and the pleasure that it generated was the antidote to the demon engendered by the capitalist industrial age. Although they lack a messianic spirit, our decorative arts also advocate a nostalgic rebirth of craftsmanship as reflected by the carvings, inlay work, leaded glass, grisailles, enamels, wrought iron, tapestries, jewellery, or the interiors, poetic hymns to everyday beauty or the new gilded cages affording protection against the buffeting of society.

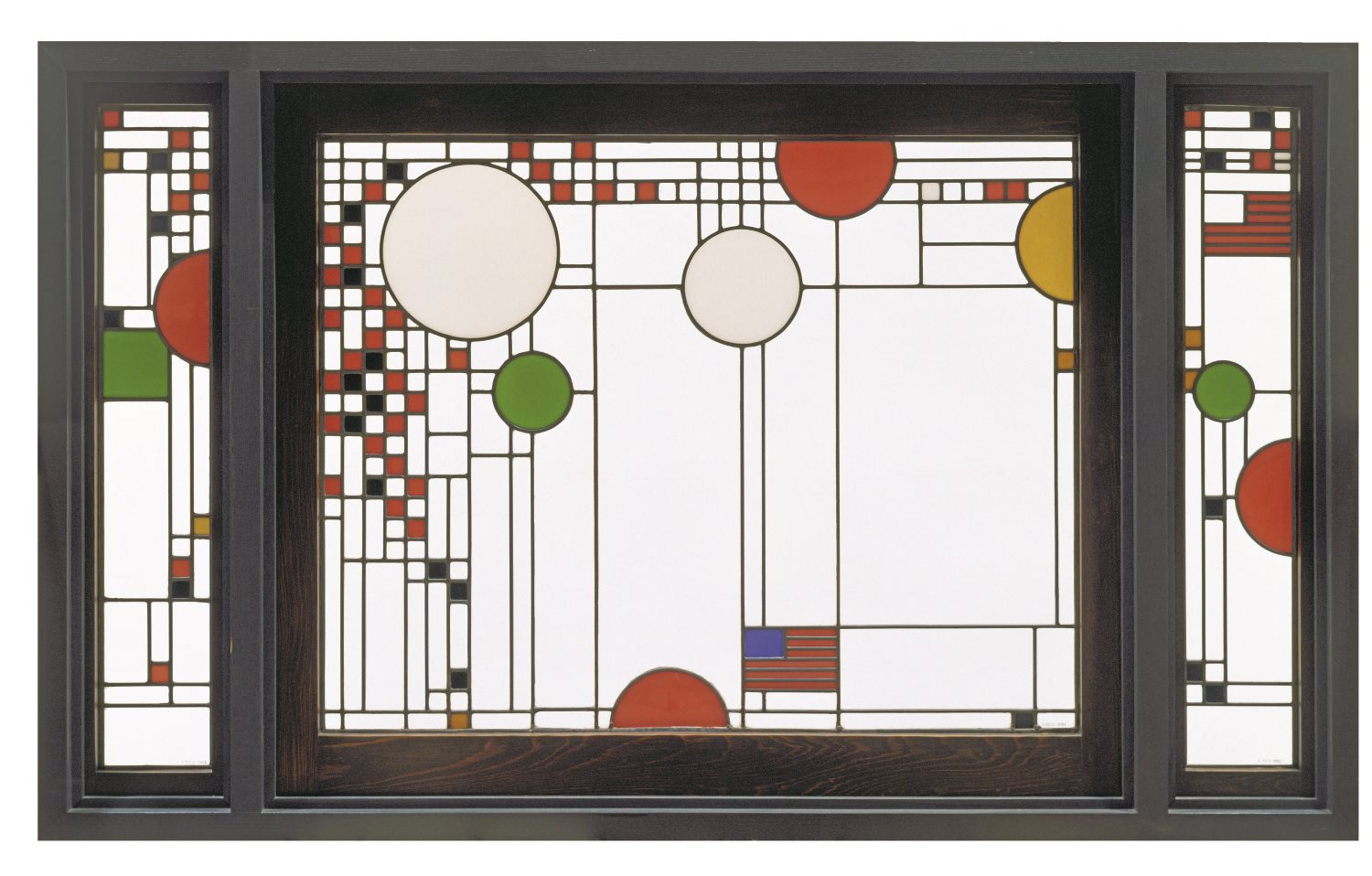

I invite visitors to the exhibition to compare the cabinet by Joan Busquets, with Limoges enamelwork and inlays, or the light in Puig i Cadafalch’s Casa Amatller, reminiscent of a medieval votive crown, with a design by Frank Lloyd Wright or the chairs by Charles Rennie Mackintosh that opened up a new path.

Frank Lloyd Wright. Kindersymphony. 1912 © Frank Lloyd Wright, VEGAP, Barcelona, 2018 / Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Consumption

With the change of century, English art became popular in interior decor. The English ceramics by Minton, sold by the furniture maker Francesc Vidal in his shop, filled dressers and trinxants in Barcelona.

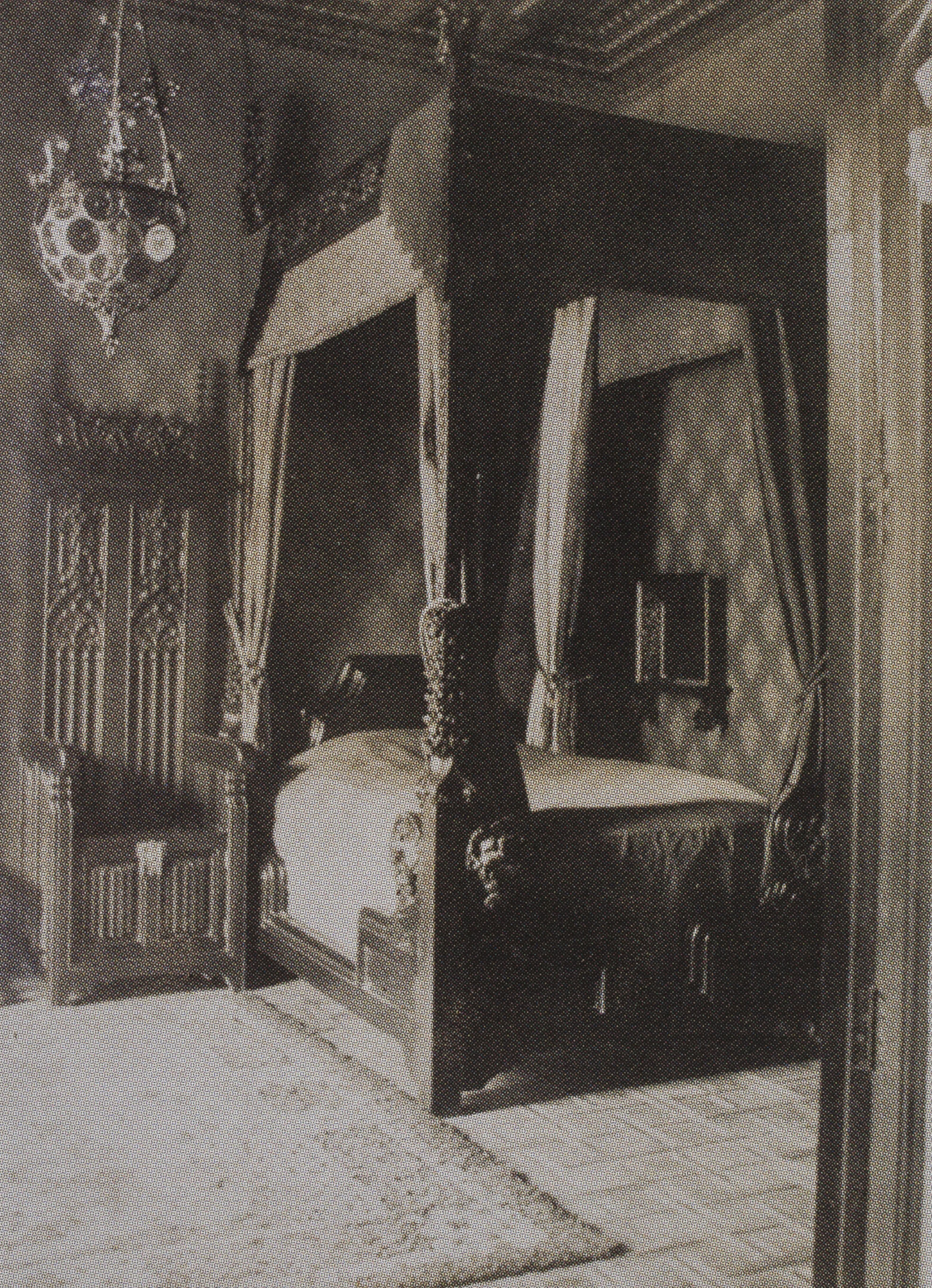

The recent restoration of Puig i Cadafalch’s Casa Amatller has revealed Liberty velvet designs by Harry Napper in the music room. Liberty fabrics were appreciated and could be bought in shops and department stores in the city as the advertising of time recalled.

Alexandre de Riquer, Antigua Casa Franch (Former Casa Franch), 1899

Casa Amatller: music room, bedroom and dining room. 1901

Related links

William Morris and Company: The Arts and Crafts Movement in Great Britain, Fundación Juan March

Alexandre de Riquer: The British Connection in Catalan Modernisme. Eliseu Trenc Ballester & Alan Yates. The Anglo-Catalan Society [PDF 1,07 MB ]

Art Modern i Contemporani