Eduard Vallès

In 2022 it is exactly 130 years since the artist Joaquim Torres-Garcia (Montevideo, 1874-1949) arrived in Barcelona. I feel the anniversary is the perfect excuse to shine the spotlight on one of the most international artists who worked – and also trained – in Catalonia. That is why we will write about his figure and work located in two very specific institutions, the Museu Nac ional (in this article and the following one), and the Institut d’Estudis Catalans, soon also on the museum’s blog.

This first text is about this artist’s presence in the collections of the Museu Nacional, discussed in chronological order for the simple reason of establishing a certain biographical correlation based on the works.

Works by Joaquim Torres-García at the Modern Art 70 room in Museu Nacional.

Torres arrived in Barcelona in 1892, just three years before Picasso did (1895), and, together with Juli González, all three of them trained as artists and took their first steps in Barcelona at the turn of the century – three artists who, as time went by, would become important names of the international Avant-garde, each of them in their respective registers.

Torres-Garcia’s bond with Catalonia was as deep as could be: not only was his father Catalan (from Mataró), and he married a Catalan (Manolita Piña), but half of his career as an artist took place in Catalonia. He actually arrived here in 1891, in Mataró on board the Giava, after changing ships in the Italian port of Genoa having travelled from his native Uruguay. He was just 17 when he arrived and after a first year in Mataró he moved to Barcelona, where he lived – with a few isolated stays elsewhere – until 1920, when he settled in New York.

The beginnings: Eclecticism and Modernism

The Museu Nacional’s collection now has a total of 13 works: ten paintings, two drawings and one wood painting. They all have very diverse origins and some of them are long-term loans. The oldest work in the collection is a drawing from around 1900 that depicts a well-dressed lady having her aperitif at a table in the open air, something that refers us to the artist’s heterodox beginnings, in which he steeped himself in the Modernista ideas of the time. This early Torres displays a production, basically small format, in which he combines portraits and landscapes within what could be called Costumbrismo, featuring the Arabesque and the whiplash in some of his drawings. In that proto-Torres Garcia, the influence of Ramon Casas the draughtsman is obvious in many of his works, from that moment date Lady 1900, a drawing that entered the Cabinet of Drawings and Prints via the Rossend Partagàs Bequest (1945).

Joaquim Torres-García. Lady 1900. Circa 1900. Gouache on paper. 34,8 x 13,4 cm.

The young artist passed through the classes at the Llotja School of Art and later worked as an illustrator on newspapers and magazines of different kinds, a period when he signed many of his works “Quim Torras”. Dating approximately from those years is the fabulous portrait that Ramon Casas did of him, in charcoal, which is also part of the Museu Nacional’s collections thanks to the generosity of Casas, who donated it in 1909.

Ramon Casas. Portrait of Joaquim Torres-García. Circa 1901. Charcoal on paper. 64x30cm.

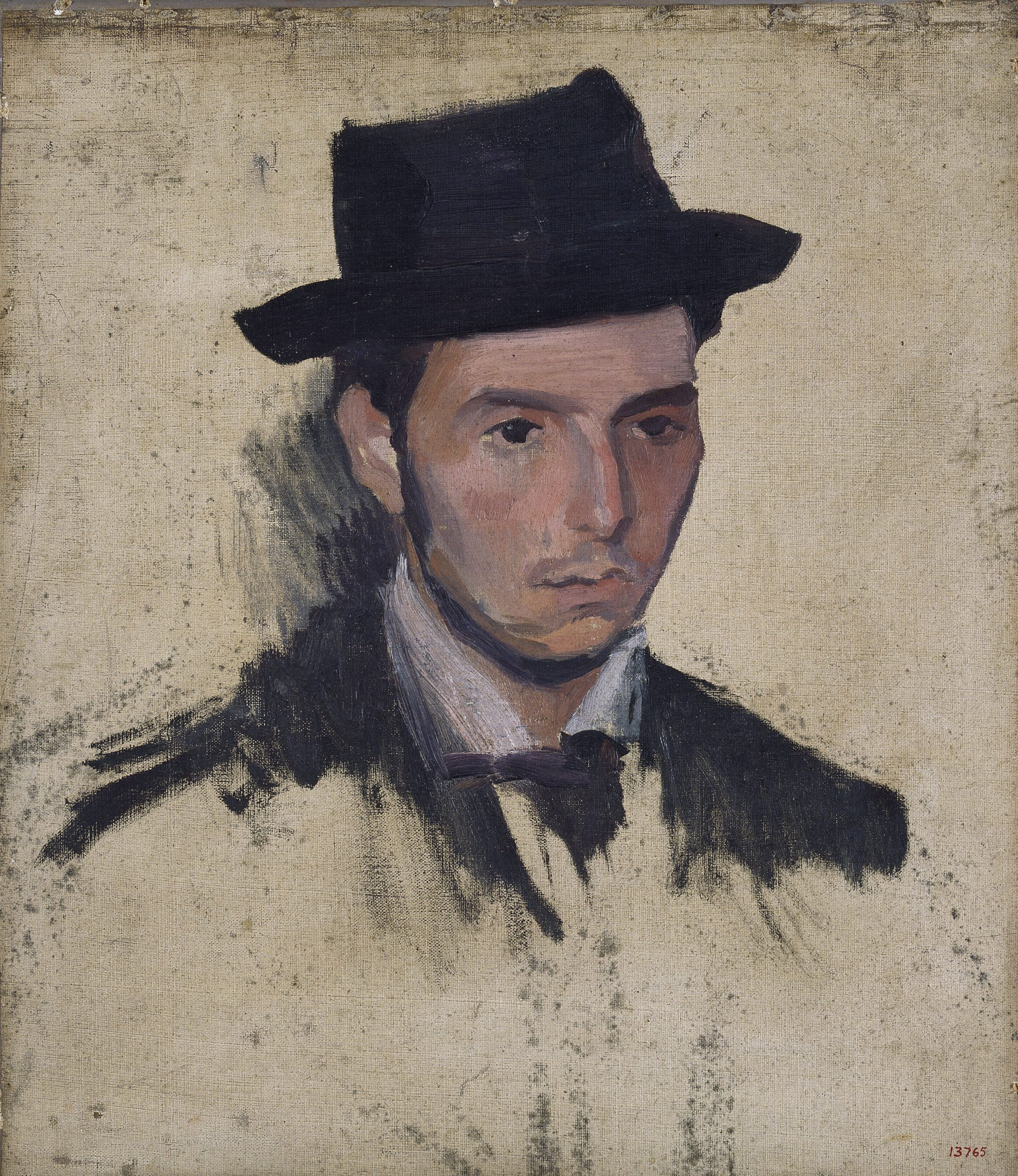

In those same years, around 1900, he did a portrait in oils of his friend Josep Pijoan. It is a portrait in which we see a young Pijoan sporting a hat in a sketched painting, apparently unfinished, which has remained as a testimony to their friendship. This work entered the museum’s collections in 1936 through a donation by Josep Pijoan Soteras.

Joaquim Torres-García. Portrait of Josep Pijoan. Circa 1900. Oil on canvas. 50x43cm.

In reality, however, Torres did not feel comfortable with the artistic ideas of his circle, nor with the Modernista aesthetic or the Impressionist whims of many of his fellow students at the Llotja, who began painting in the outskirts of Barcelona. As he writes in his book – written in the third person – Historia de mi vida (The Story of My Life), “the city’s suburbs, to be painted imitating the Avant-garde painters of the time”. He immediately names some artists in particular with whom he had dealings: Joaquim Sunyer, Joaquim Mir, Isidre Nonell and Ricard Canals. He was in actual fact a privileged witness to the beginnings of what historians now know as the Colla del Safrà or Colla de Sant Martí. He also painted landscapes in those years but, with the odd exception, they were basically sketches, often of the city, far removed from the aesthetic of that group of artists. Once again in Historia de mi vida Torres talks about how far away he felt from Modernista ideas, while at the same time announcing his leaning towards the classical world, with an undeniable point of reference, the artist Puvis de Chavannes: “[Torres-Garcia] began doing something like advertising posters. Steinlen, Lautrec, were his masters. But he was not yet that, what was he going to be! He had to seek a higher tone, and he found it immediately in Puvis de Chavannes […] He was gradually leaving that decorative style of advertising posters behind, in order to seek more noble forms, more serene lines, more serious rhythms”.

This change took shape in 1901, approximately. A landmark in his public projection was the monographic article dedicated to him that year by the magazine Pèl i Ploma, written by Miquel Utrillo (Pèl i Ploma, July 1901, no. 78). That issue was illustrated on the cover with a composition by Torres, The Fountain of Youth, clearly inspired on Puvis, and on the pages inside no less than eight of his paintings were reproduced. One of these paintings, Nightfall, which was added to the Plandiura Collection that was purchased by the authorities in 1932, is now in the Museu Nacional’s collections: a small-format nocturnal view depicting the garden of a house probably in Barcelona, one of the recurring scenes in the compositions of that early Torres.

Joaquim Torres-García. Nightfall. Circa 1901. Oil on canvas. 28x40cm.

The neoclassical twist: the Mediterranean Arcadia

The influence of Puvis had a twofold impact on the artist: first, the iconographical incorporation of the sublimated Mediterranean world, with the sea, fountains, cypresses, olive trees and small pavilions, a creative world that falls completely in what would later be known as Noucentisme. Moreover, the mark of Puvis would also become explicit with his interest in fresco painting, which would produce important results in the following years. One of the most emblematic pieces in the Museu Nacional is Temple to the Nymphs, a work from the Júlia Corominas Bequest (2011). It is a composition that replicates some of the iconographical features mentioned above in Puvis’s work, along with a similar colour range, with a certain predominance of pastel colours. Notable in this painting are the pavilion in the background, several figures walking in a line wearing long tunics and a couple talking. The cypresses and the swans give a harmonious and pleasing air to a composition framed by the bluish colours of the water and the sky.

Joaquim Torres-García. Temple to the Nymphs. Circa 1901-1911. Oil on canvas. 58x91cm.

The Museu Nacional’s collections have several pieces that follow this aesthetic, with an iconography almost always dominated by images of women. The paintings Ripe Fruits and Orange Trees by the Sea present two women naked from the waist up situated in a sort of Arcadia of clearly Mediterranean echoes, after all one of them features grapes and the other oranges. Both of these paintings are also from the legendary Plandiura Collection purchased in 1932.

Joaquim Torres-García. Ripe Fruits. Circa 1905. 38x50cm. / Orange Trees by the Sea. Circa 1911. 40×50,5cm.

A third painting, Village Women, falls within a line parallel to the mythical, which consisted in immortalizing scenes of a rather more domestic nature: People talking in the street, pictures of village squares, farmers working, etc. Village Women, a work that was acquired by the museum in 1998, is one of this group of paintings in which the scenes may be said to show a less sublimated view – in this case the female figures are fully dressed – but, I insist, with unequivocal associations with the productions of a more Arcadian conception.

Joaquim Torres-García. Village Women. 1911. Oil on canvas. 75,5×100,2cm.

Art modern i contemporani